Name of Thrones

If you want to know what really mattered to a medieval king or queen, look at what they called their children. The names given to royal offspring reveal rebellious, pious and pretentious parents.

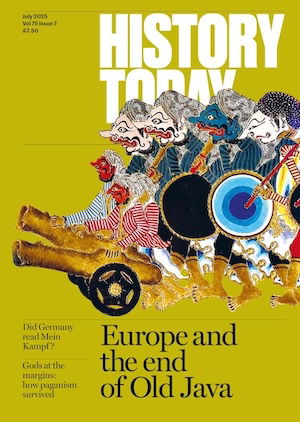

The coronation of Edward III, early 14th century.

The lives of the kings and queens of England are among the best documented of the medieval period. Yet though we might be familiar with the objective details of a monarch’s reign – the battles they fought, the alliances they forged, even the intrigues of their courts – insights into what mattered to them personally are often elusive.

Naming a child then, as now, was a highly personal and symbolic gesture – and, with knowledge of a name’s context – a revealing one, too. The names that medieval monarchs chose for their children can show us what they wanted to convey about their family and their dynasty; what their relationships with their extended families were like; the literature that mattered to them; which saints they felt close to; and whether they were conformists or rebels.

Breaking with the Past

Consider Henry III, who became king of England at the age of just nine in 1216. Henry would become England’s fourth-longest ruling monarch, but the country he inherited was mired in civil war and dangerously close to military defeat by Prince Louis of France, later Louis VIII, who invaded England and even captured Winchester in 1216. During the first 16 years of Henry’s reign, his kingdom was controlled by courtiers, first Hubert de Burgh and then Peter des Roches, culminating in a turbulent period in which Henry combatted – and put down – a brief revolt led by Richard Marshal, son of William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke.

In 1234 Henry began his personal rule. Two years later, in 1236, he married Eleanor of Provence, a union which gave him access to influential figures in mainland Europe; Louis IX of France was now his brother-in-law, and his new extended family had a strong relationship with the Pope. Henry was 28 at the time of the wedding; Eleanor was 12.

Over the next 14 years, Henry and Eleanor had five children: Edward (b.1239), Margaret (b.1240), Beatrice (b.1242), Edmund (b.1245) and Katherine (b.1253). The names Henry and Eleanor chose for their sons, Edward and Edmund, were extremely unusual at the time; neither had been used in the royal family since the Norman Conquest in 1066.

Edward was named after the royal saint Edward the Confessor (1042-66). Henry had demonstrated a commitment to the Anglo-Saxon saint since the culmination of the civil war that had marred the beginning of his reign. He had adopted Edward as his patron saint, attracted by his famously peaceable nature and perhaps identifying with his position as a royal orphan. His devotion culminated in the reburial of Edward’s remains in the especially rebuilt Westminster Abbey in 1269.

Edmund was named after St Edmund the Martyr, the ninth-century king of East Anglia. Both names – reaching into a distant past – explicitly linked Henry and Eleanor to Anglo-Saxon royal saints and ignored traditional, warlike Anglo-Norman names, such as William, Richard or Robert, which had been used in the royal family from the time of the conquest. Clearly, the names of their two heirs apparent were chosen to signify a break with the past. Why?

The answer is found in the more recent past. Henry had inherited the throne from his father, John, in 1216, just a year after he had been compelled to sign Magna Carta. John was an unpopular king who struggled in a crisis. He was rumoured to have murdered his nephew, Arthur of Brittany, and was considered responsible for the loss of the French lands of Anjou and Normandy. But it was not just John’s reputation that needed exorcising. John was the last member of a family riven by conflict. The Angevin dynasty descended from Geoffrey of Anjou and his wife, the Empress Matilda, whose claim to the throne of England, inherited from her father Henry I, was passed on to her son, Henry II. John’s older brothers, Henry, Richard and Geoffrey, rebelled against their father, Henry II, in 1173 with the support of their mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine. Some years later, John would revolt in turn against his brother, Richard I. With the names of their sons, Henry and Eleanor sought to distance themselves from Henry’s immediate ancestors and their troubled, martial lives. ‘Edward’ and ‘Edmund’ harked back to a pre-Conquest era, and were part of a campaign to demonstrate Henry’s commitment to English piety. Arguably, in this, Henry enjoyed success; he was considered a pious and peaceful man, known for rebuilding Westminster Abbey in 1245 and for his lack of interest in tournaments or war.

The royal couple adopted a different strategy when naming their daughters. Henry and Eleanor would have known that their daughters were likely to marry influential aristocrats from outside England and so would spend their adult lives in noble courts abroad. Names which asserted their Englishness were therefore less important than for their brothers, who would remain at home. Like Edward and Edmund, Margaret, Beatrice and Katherine had not been used before by the English royal family. We are fortunate that contemporary chroniclers recorded not only the names given to Henry and Eleanor’s daughters, but also the reasons behind them. Of Margaret’s birth in 1240, Matthew Paris writes:

Queen Eleanor gave birth to a daughter of the king. And she was given the name Margaret, which is the name of her maternal aunt, the French Queen, and because [Queen Eleanor] called upon St Margaret in the pain of childbirth.

Of Beatrice, born two years later, the author of the London Annals records:

Queen Eleanor gave birth in Burgundy to a daughter, and she was called Beatrice, at the request of the Countess of Provence [Eleanor’s mother], who was so named.

Both, then, were named after members of Eleanor’s non-English family. According to Matthew Paris, the youngest daughter Katherine was named after St Katherine of Alexandria, an increasingly popular saint, frequently commemorated in contemporary literature and art, because she was born on St Katherine’s Day. Throughout his reign Henry was criticised by his magnates for the support he gave to foreigners – and particularly to members of his mother’s and wife’s family – in England.

The names that Henry and Eleanor chose for their children create a portrait of a religious couple, keen to emphasise their piety by drawing links with newly fashionable virgin martyrs, as well as one hoping to move away from a fractious past. Henry may have had close and affectionate relationships with his siblings, but none of his children were given names from his family; not his parents John or Isabel of Angoulême, his illustrious grandparents Henry and Eleanor of Aquitaine or his siblings Richard, Joan, Isabel or Eleanor. This was a clear separation from the turbulent Angevin dynasty; that it was a deliberate choice is made clear by the fact that the royal couple did not shy away from using names found in Eleanor’s family. With the names of his children, the pious king reveals himself as something of a rebel.

Keeping it in the family

Henry was succeeded by his eldest son Edward I in 1272, when Edward was 33. Edward proved to be a more active and vigorous king than his father. In the early years of his reign, he oversaw significant administrative and legislative reform, beginning with a vast enquiry into the state of the realm, followed by statutes on a variety of themes including land tenure, debt and the maintenance of law and order. Later, Edward – far more prone to fighting than his father – turned to war, first in Wales and later in Scotland. A different king in temperament to his father, his naming strategies were different, too.

Edward married Eleanor of Castile in 1254. He was 15, she a year younger. Eleanor was the daughter of Ferdinand III of Castile and Joan, Countess of Ponthieu. The couple had at least 15 children, although the names of only 12 are known for certain: Katherine, Joan, John, Henry, Eleanor, a second Joan (following the death of her older sister), Alphonso, Margaret, Berengaria, Mary, Elizabeth and Edward.

Unlike his parents, Edward and Eleanor chose names that were already in use in his family: Katherine and Margaret were the names of Edward’s younger sisters; John, was his grandfather, the former king; Henry was Edward’s father. Eleanor could have been named for any one of the (at least) three Eleanors from whom she was descended. The only name that was not a reference to a family member was Elizabeth, given to their eighth daughter.

Some of the names chosen would have been completely alien to English ears at this time. Berengaria and Mary were popular names in the Castilian royal family and although there had once been an English Queen Berengaria (the wife of Richard I, 1189-99) she held the dubious honour of being a queen of England who never set foot in the country during her husband’s lifetime. Alphonso was the name of Edward’s new brother-in-law, the learned and cultured Alphonso X of Castile. Alphonso agreed to act as his new nephew’s godfather in 1272, and the choice of name demonstrates the affection and respect Edward had for his brother-in-law. It was almost unheard of in contemporary England and its choice raised the real possibility of a King Alphonso of England. Alphonso of Chester acted as Edward’s heir for 10 years before his death in 1284.

No religious motivation is discernible in the names chosen by Edward and Eleanor. Instead, they revisited names which Henry III had chosen to avoid, including the ill-fated John. Unlike Henry, Edward did not name his children as part of a considered campaign to convey a careful message about what mattered to him as a ruler; instead he demonstrated his respect for his wife, her family and his own ancestors. Militarily inclined Edward revealed himself to be far more conventional than his pious father.

Literary Aspirations

Born in 1312, Edward III was the oldest child of Edward II and Isabel of France, and the grandson of Edward I. He ascended to the throne in 1327 after his mother and her lover, Roger Mortimer, deposed his father. However, Edward’s personal reign did not begin until 1330, when he was 17 and took Mortimer captive with the assistance of a small group of companions. Edward became engaged to Philippa of Hainault in 1326 as a result of his parents’ feuding. Isabel had secured support in her mission to depose Edward II from Philippa’s father William of Hainault, in return for his daughter’s marriage to her son.

The young couple married at York on 24 January 1328, when Philippa was possibly just 13. Edward III was a popular king, his reign was characterised by domestic peace and expensive wars with Scotland and France. He presented himself as a cultured, chivalric man. He founded the Arthurian-inspired Order of the Garter – now the most senior and prestigious order of chivalry in Britain – in 1349 and carried out major building works, such as the rebuilding of Windsor Castle, to create conditions suitable for grand chivalric displays.

Edward and Philippa had a large family and many of their children were named for family members. These included Edward, Isabel, Joan, William, John, Edmund, Margaret, Thomas, a second William and a second Thomas. The repetition of Thomas and William suggest that the royal couple were especially keen for one of their children to carry these names, though it is also possible that they had run out of other ideas.

Two of their chosen names stand out, however: Lionel and Blanche. Lionel was the couple’s third son, born in 1338, when Edward and Philippa were in their early twenties. Their first two sons had been given the names of their grandfathers. Family duty discharged, the couple chose the name Lionel after the knight of the Round Table, who emerges in Arthurian literature in the early 13th-century Lancelot-Grail stories. The name is not found in England before the 14th century and Edward and Philippa’s son was one of the first English bearers of the name (although he was born and named in Antwerp).

Here, Edward sought to strengthen his association with Arthurian iconography, something he had cultivated throughout his reign. Stories of the legendary King Arthur were first popularised by Geoffrey of Monmouth in the mid-12th century. Soon French romances detailing the lives of Arthur’s companions and introducing characters such as Lancelot and Gawain, became popular across the courts of Europe. Edward had appeared as ‘Monsieur Lionel’ at a tournament in Dunstable in 1334, bearing arms associated with the Arthurian Gawain. The choice of name is clearly a product of his youthful aspirations.

Just as Lionel was the third son, Blanche was the third daughter, with her two older sisters given the names of their grandmothers. The name Blanche had not been used in the English royal family before and was not common in England. Like Lionel, it has Arthurian connotations: Tristan’s wife in the tragic love story of Tristan and Isolde is Isoud le Blanche Mains, or Isolde of the White Hands. ‘Blanche’ thus references a popular Arthurian story without associating the bearer with the story’s other Isolde, the adulterous queen of Cornwall, Tristan’s lover, after whom the story is named.

Arthurian names were part of Edward and Philippa’s creation of a chivalric court and their wish to be seen as cultured, educated rulers; Edward was known for his adherence to the codes of chivalry and the associated protocol. The couple avoided the names of controversial, prominent or immoral villains such as Tristan or Guinevere, but favoured those of upstanding characters in supporting roles. The intention was to give a subtle indication of Arthurian influence, without overpowering the conventional names of their other children.

Across three different medieval royal families we see naming strategies deployed for a variety of reasons: to display familial loyalty and affection; to break with a contentious past and cultivate an association with a nobler, older one; to display piety; to show off a monarch’s education and cultural preferences. In each case, the names convey coded messages about what mattered to the royal parents. A nuanced consideration to names chosen five or six hundred years ago, reveals the pious, affectionate or rebellious men and women who gave them.

Rachel Tod is a DPhil candidate in Medieval History at the University of Oxford, working on personal name choice among the medieval aristocracy.