John F. Kennedy’s Warning to the Republic

A Cold War thriller imagined the United States caught in the midst of a military coup. Surprisingly, it was endorsed by the president himself, who recognised its power as a cautionary tale.

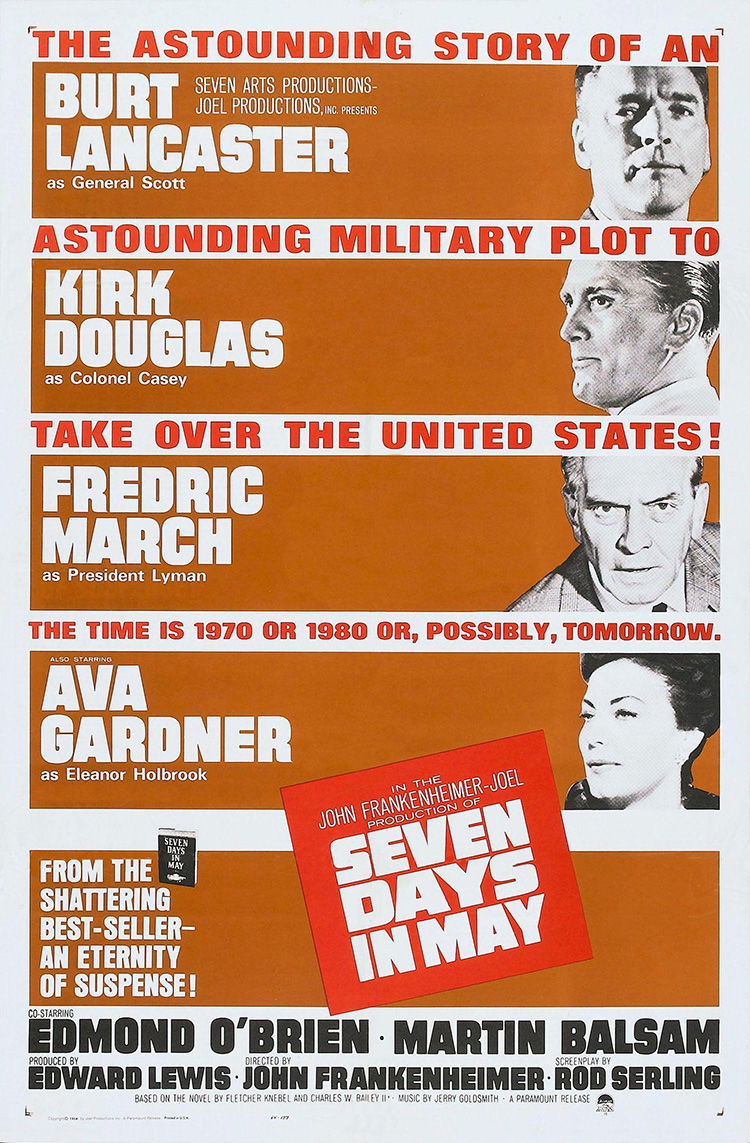

Kirk Douglas in Seven Days in May, 1964.

It marked a turning point in the Cold War: the president of the United States had just signed a nuclear disarmament treaty with the Soviet Union. The US military’s top brass were furious, having warned that the treaty endangered national security. But the president had signed it anyway. To the generals, that amounted to treason. They assembled a secret combat unit to topple the president. A coup d’état was coming; the American Republic would fall.

The plot of the Hollywood film Seven Days in May (1964) is, of course, fiction. But its journey to the screen is historically significant, because the person who got the ball rolling on the production in 1962 was not a Hollywood mogul but someone with even more power: President John F. Kennedy.

JFK more than earned his reputation as a playboy. But he was also an avid reader, a habit formed during years of illness and forced bedrest. The president favoured history (he was a subscriber to History Today) and spy novels. When in 1962, midway through his tenure, he received the galleys of a new thriller about a military takeover of the US government he read it eagerly.

The pulpy novel, written by Fletcher Knebel and Charles Bailey, was partly inspired by events in Kennedy’s presidency. Knebel and Bailey were seasoned political reporters. They began writing Seven Days in May after interviewing General Curtis LeMay in the wake of the failed 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion, when the US landed anti-communist rebels in Cuba to depose Castro. LeMay blamed JFK for aborting the operation too early, accusing him of ‘cowardice’. The more Knebel and Bailey investigated, the more they realised that the military establishment and the intelligence community despised Kennedy.

The feeling was mutual. After the Bay of Pigs, JFK publicly assumed responsibility for the debacle. Privately, however, he was furious, swearing from then on ‘never to rely on the experts’ and ‘to watch the generals’. Soon, an event would put this resolution to the test: the Cuban missile crisis. For 13 days in October 1962, the US and the Soviet Union were locked in a standoff over the latter’s deployment of missiles in Cuba. The stakes were gigantic: nuclear war might erupt any second. The generals urged Kennedy to bomb Cuba. Reluctant to trigger a Third World War, he instead ordered a naval blockade of the island. Raging, LeMay told the president ‘that was almost as bad as the appeasement at Munich’.

Yet Kennedy stayed the course, successfully negotiating a diplomatic solution with the USSR. LeMay considered it to be ‘the greatest defeat in our history’. JFK’s opinion of the military decreased further. Their attitude during the crisis showed that they posed a threat to humanity’s survival. He told his inner circle ‘the military are mad’ and if ‘we do what they want us to do, none of us will be alive’. It didn’t take much for Knebel and Bailey to imagine a situation in which the army might foment a coup.

After reading Seven Days in May, Kennedy remarked ‘it could happen’ and some generals ‘might hanker to duplicate fiction’. The possibility of a coup – and the threat of his own assassination – was a leitmotiv in Kennedy’s conversations with friends. The president had a dark sense of humour and often joked about it. On one occasion, he called Chuck Spalding to announce he was writing a novel about a coup led by Vice President Lyndon Johnson. Kennedy would sporadically update Spalding: ‘I’ve just got the second chapter’, he once quipped, ‘Lyndon has me captured just as I hit the pool!’.

One summer at their Cape Cod retreat, Kennedy talked his wife, Jackie, into making a short film together. The theme was his assassination. The president was the star but the first lady took directing duties. She enlisted Secret Service agents as co-stars, explaining ‘we’re making a movie about the president’s murder’, directing them to ‘look desperate, like you heard shots’. The film’s eerie climax featured Kennedy collapsing as gunshots were fired at him, fake blood (perhaps tomato juice) spilling from his mouth. As historian Thurston Clarke comments, ‘the skit reflected … [Kennedy’s] rich but carefully concealed fantasy life’. It also reveals the president’s innermost fears and his way of coping with them.

Kennedy thought Seven Days in May should become a movie. Arthur Schlesinger, a presidential adviser, said Kennedy wanted the film ‘made as a warning to the generals’. The president reached out to Hollywood contacts and learnt Kirk Douglas, the star and producer of Spartacus, wanted to adapt the novel for the screen. In reality, Douglas was on the fence. He liked the ‘risky’ material but had been advised by peers ‘to stay away from it’ for fear of offending the government. That changed when Kennedy accosted Douglas at a Washington banquet. ‘Do you intend to make a movie out of Seven Days in May?’, the president asked, before explaining why it would make ‘an excellent movie’.

Encouraged, Douglas bought the rights and asked John Frankenheimer, who had enjoyed recent success with the Cold War thriller The Manchurian Candidate, to direct. Frankenheimer agreed, sensing an opportunity to show ‘what a tremendous force the military/industrial complex is’. Pierre Salinger, the president’s press secretary, gave the director a tour of the White House for research purposes. He also explained that, for Kennedy, the film represented ‘a warning to the republic’. It was certainly a way of alerting public opinion and, as Schlesinger put it, ‘raise consciousness about the problems involved if the generals got out of control’.

Seven Days in May attracted an all-star cast: Burt Lancaster played the general behind the coup, Ava Gardner his lover, Fredric March the president and Kirk Douglas a military whistleblower. It was filmed over the summer of 1963. One scene was shot in front of the White House with Kennedy’s blessing. The Pentagon, however, denied the production filming permits since Frankenheimer would not submit the script for ‘consideration’, aware that the military authorities would demand changes. Yet the crew still managed to shoot there; Frankenheimer hid a camera inside a van while Douglas, dressed as a colonel, strode incognito into the Pentagon, even saluting a guard on his way in.

During filming, real life imitated fiction. In July 1963 JFK announced that, like the fictional president in Seven Days in May, he had struck a nuclear deal with the Soviet Union. The Test Ban Treaty – the first arms control agreement of the Cold War era – outlawed most nuclear testing. It was seen, by both supporters and detractors, as opening a peace process with the Soviet Union. The British prime minister Alec Douglas-Home deemed it ‘the beginning of the end of the Cold War’. Although it was ratified by the US Senate in September 1963, Kennedy’s treaty was initially opposed by most of the military.

Seven Days in May was released in February 1964 and was well-received by audiences and critics. Variety magazine called it ‘realistic’ and ‘provocatively topical’. What did John Kennedy think of the film he had helped get made? He never saw it; he had been assassinated three months earlier.

Theo Zenou is studying for a PhD on John F. Kennedy at the University of Cambridge.