The Return of Protectionism

US presidential candidates are reprising the arguments of a century ago.

Free trade is under fire in the United States. The Democratic Party hopeful Bernie Sanders lambasts free trade agreements for forcing ‘American workers to compete against desperate and low-wage labour around the world’. Republican frontrunner Donald Trump has called for 45 per cent duties on Chinese products and punitive tariffs on US companies that build factories abroad. ‘History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme’, Mark Twain is attributed as saying and the mounting opposition to trade liberalisation has echoes of Twain’s Gilded Age America, when opposition to liberalisation became the foundation of US political economy and foreign policy. The embrace of free trade by America’s political elites arose only in the wake of the Second World War.

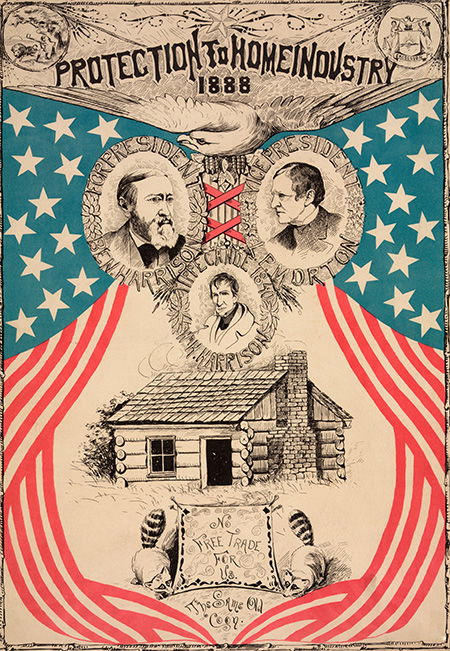

At the end of the Civil War, in 1865, the Republican party rebranded itself as a supporter of protectionism, introducing high tariffs alongside government subsidies for US industry. Such policies, directed at Britain, bastion of free trade, saw Adam Smith’s invisible hand hiding behind protectionist walls.

In the late 19th century the US and Britain had a very different relationship from the ‘special’ one of today. Anglo-American relations were riven with tensions reflected in Republican trade policy, which reflected a fear of the unfettered competition that would advantage Britain’s advanced industries.

Anglophobia became entwined with the GOP’s defence of economic nationalism, which promised to protect the high wages of American workers and to help allay widely held fears that America’s nascent industries would be pulled prematurely into Britain’s orbit.

Not all Americans agreed that the Republican party’s mixture of economic nationalism and imperial expansion was the best approach for the creation of US wealth, but, with shades of Trump’s conspiratorial view of China, Anglophobic paranoia arose when US supporters of free trade began to mobilise and to work closely with allies in Britain.

A vocal minority of American free traders, in emulation of Britain’s liberal system, desired an end to US protectionism and sought instead to make peaceful expansion into foreign markets through international trade liberalisation. They based their vision for US economic globalisation on the Victorian ideology known as Cobdenism, named after Britain’s free-trade apostle Richard Cobden, the radical politician who had led the charge in overthrowing British protectionism in the 1830s and 1840s and who threw himself into the international peace movement until his death in 1865. His philosophy gained an influential following in the US, including abolitionists such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Ward Beecher and William Lloyd Garrison, who subscribed to his belief that international free trade and a foreign policy of non-interventionism would bring peace and prosperity, not just to the US and Britain but to the world. Protectionist policies in their view precipitated tariff wars, geopolitical rivalry and global conflict. But their idealistic fight for free trade and peace was an uphill battle.

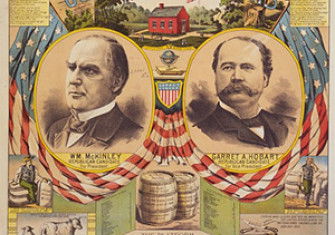

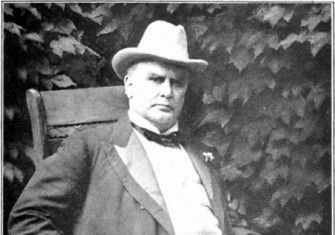

Republican conspiracy theories stalked the postbellum free trade movement. When these same Cobdenites appeared to be gaining the upper hand in US politics in the early 1890s, the future Republican president William McKinley – a man who had earned the nickname ‘the Napoleon of Protection’ – exemplified the GOP’s protectionist paranoia. He suggested that a transatlantic free trade conspiracy was at work. McKinley himself charged that it was ‘beyond dispute’ that a partnership existed ‘between Democratic free trade leaders in the United States and the statesmen and ruling classes of Great Britain’.

Only a handful of years later, in 1897, the Napoleon of Protection found himself in the White House just in time to witness the dawning of a new American century and to oversee the acquisition of a colonial empire.

Republican economic nationalism found its foreign policy complement in turn-of-the-century jingoism. An economic depression from the 1870s to the 1890s enhanced the perception that the US needed more foreign markets for its surplus goods and capital. Imperially minded Republican protectionists developed new coercive methods for obtaining new markets, culminating in the Republican acquisition of a colonial empire during the Spanish-American War of 1898. From then on, Republican protectionists would direct the imperial course of US economic expansion throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Today’s heated debate over US trade policy rhymes with the great tariff debate of the late 19th century. The 2016 presidential campaign trumpets the return of protectionism. Reflecting the paranoia of Republicans past, those who support free trade initiatives are now charged with being part of a vast conspiracy to undermine American democracy. As in the American Gilded Age, the future of US – and world – economic globalisation once again hangs in the balance.

Marc-William Palen is Lecturer in Imperial History at the University of Exeter and author of The Conspiracy of Free Trade: The Anglo-American Struggle over Empire and Economic Globalization, 1846-1896 (CUP, 2016).