The World of Medieval Dogs

The people of medieval Europe were devoted to their dogs; one great French dog-lover declared that the greatest defect of the species was that they ‘lived not long enough’.

Detail from Tacuinum Sanitatis, 14th century medieval handbook of health.

The later middle ages, and the years immediately following, were one of the most ‘doggy’ periods in history. Hunting and hawking were by far the most popular sports of the leisured classes, who also liked keeping dogs simply as pets; and the rest of the population used them for protection and herding. Performing dogs were much admired, and people loved to hear fabulous yarns of the extraordinary fidelity and intelligence of dogs.

Indeed, the great Duke of Berry went personally to see a dog that refused to leave its master’s grave, and gave a sum of money to a neighbour to keep the faithful beast in food for the rest of its days. True, rabies was unpleasantly common; but that was one of the ills that flesh is heir to, not to be held against the canine race – and for the bite of a mad dog you had a wide choice of remedies, ranging from goat’s liver to sea bathing.

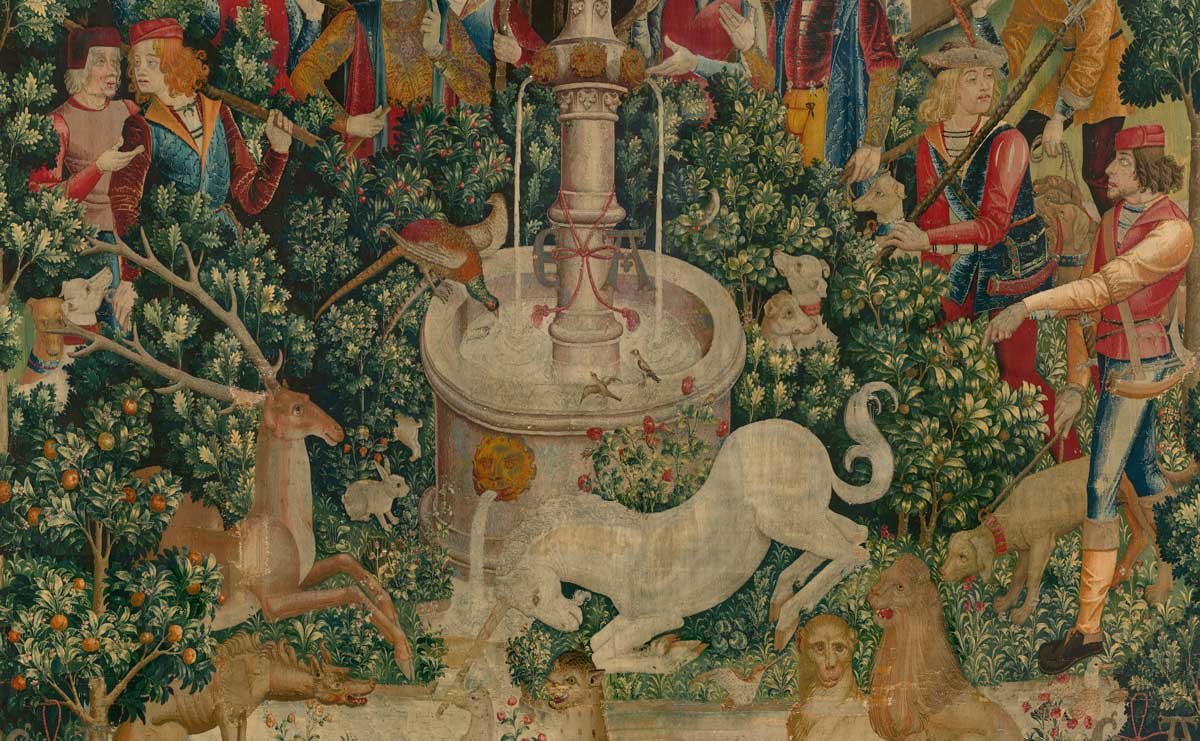

The aristocrats of medieval dogdom were greyhounds and what our ancestors called ‘running hounds’, by which, illogically, they meant dogs that hunt by scent rather than speed. By greyhounds they meant anything of a greyhound type, from an Irish wolfhound to a tiny Italian greyhound, which is one of the difficulties facing dog-genealogists. A greyhound, the favoured gift of princes, was the usual hero of the medieval dog story.

He should, says a 14th-century writer, be courteous and not too fierce ‘wel folowing his maistre and doyng whatever he hym commandeth, he shuld be good and kyndly and clene, glad and joyful and playeng, wel willyng and goodly to all maner folkes save to the wild beestis’. This paragon was the noble lord’s special pet, and his effigy was often placed on tombstones at his master’s feet. The knight’s lady was apt to have lap dogs, and their effigies, too, singly or in pairs, are found carved on tombs, complete with collar and little bells.

Toy dogs, like fashionable clothes, always seem to provoke moralists’ ire, and one 16th-century critic, declaring that they were sought for to satisfy ‘Wanton women’s willes’, condemned them as ‘instruments of follie to play and dallie withal, in trifling away the treasure of time, to withdraw their minds from more commendable exercises, a sillie poore shift to shun their irksome idleness’.

The smaller ‘these puppies’ are, he goes on to say, the more pleasure they provide as

plafellows for minsing mistresses to beare in their bosoms to succour with sleep in bed and nourish with meate at board, to lie in their laps and licke their lips as they lie in their wagons and coches ... Some of this kind of people delight more in their dogs, that are deprived of all possiblities of reason, than they do in children that are capable of wisdome and judgement

It has a familiar ring, and this stern admonisher would have been painfully shocked by the clerical author of an earlier and popular encyclopedia who listed among the commendable traits of the species the fact that a dog will warn his mistress and her lover of the master’s approach. But moral discussions apart, what were these toys like? Some of them resembled pugs, but with longer noses. They came with long hair and short, the smooth-coated being more common, and extremes of build such as dachshund legs were not to be found.

Ears might be short or drooping and tails were worn long, our ancestors apparently seeing nothing indecent in a normal tail. Many tombstones and brasses show dogs larger than lap dogs (possibly hounds) and obviously commemorate special pets – notable among these is the tomb of the Black Prince in Canterbury Cathedral. Sometimes the dog’s name was added too, and ‘Jakke’ and ‘Terri’ still eye us gravely across the centuries.

Much has been said about medieval dogs fighting over bones under the table in the great hall, and often enough they did, but 15th-century books of etiquette pronounced it bad manners to stroke a dog or cat at meals or to make one ‘thi felow at the tabull round’, and enjoined the valet preparing his master’s bedroom to ‘dryve out dogg and catte’.

But owners’ notions varied, then as now, and a lady protagonist of hunting stated that spaniels and greyhounds slept on beds, proving that dogs’ tastes remain the same. Actually, dogs were regularly present at the kind of functions to which we would never dream of admitting them. They were often in evidence at royal courts, and, etiquette rules notwithstanding, the Duke of Berry’s Très Riches Heures depicts two small dogs right on the table at a ducal feast while in front of it a servant feeds an expectant-looking greyhound.

The Duke, in fact, was a great animal lover who kept a menagerie as well as extensive kennels. In those simpler times people travelled with dogs without arousing comment or difficulty – Chaucer’s tender-hearted Prioress had her lap dogs, and his hunting Monk his greyhounds.

Our ancestors even brought their dogs to church, a practice to which the authorities objected strenuously but not, it would seem, effectively, judging by the repetition of the protests; one of the most plaintive is a 15th-century monastic regulation against dogs and puppies which ‘oftentimes trouble the service by their barkings, and sometimes tear the church books’.

The average man’s dog, however, earned his keep. In a society with no police and plenty of lawless characters, the watch dog had an important place. For maximum efficiency he was supposed to be shut up by day to sleep so as to be fully on guard at night. Many guardians were simply big dogs, but the most highly regarded were usually mastiffs (something like their modern descendants) or alaunts.

Of Spanish origin, alaunts were large, active beasts built something like greyhounds, but heavier, with coarse heads, short muzzles and prick ears (possibly cropped). They came in various colours, preferably white with black spots near the ears. The better-bred ones, or alaunts gentils were valued for hunting, but the coarser variety were in demand as watch dogs and were used by butchers to help herd cattle – they could, it was noted, be fed cheaply on ‘the foule thinges of the boochers rowe’.

They were capable of holding an escaped ox, which made them the obvious choice for bull-baiting. They had a reputation for ferocity and contemporary illustrations often show them carefully muzzled. Shepherds and swineherds, of course, had to have dogs, but they were of no well-defined type and were as much for protection against thieves and wolves as for herding.

Other labourers had their dogs, too, earning this praise from the 13th-century encyclopedist, Bartholomew the Englishman: ‘the mungrell curres, which serve to keep the bottles and bags, with vittell, of ditchers and hedgers will be sooner killed of a straunger than beaten off from their masters apparell and victuall’.

The ubiquitous terrier was also on the scene and was used, as his name implies, in pursuing foxes to their earths, but it is disappointing to his modern friends to find few references to him. Apparently he was simply taken for granted, and fox-hunting rated little notice in those days, as our practical forbears preferred edible game.

Spaniels (so called because they came from Spain) were required for the popular sport of hawking, which attracted many as being both cheaper and less strenuous than hunting. The distressingly sheeplike build of these early spaniels would pain modern fanciers. They were wavy-coated, fairly large and usually more leggy than most of their descendants, with shorter leg ‘feathers’. Their tails were not generally cut, and it is tempting to speculate that the bob-tailed spaniels in the Très Riches Heures are early Brittanys, which are nowadays born short-tailed.

It was held that the hair on the tail should be, if anything, longer than on the body. They were white, or tawny, or speckled, with heads strange to modern eyes, having rather pointed noses inclined to turn up. Nevertheless, they functioned competently enough, and were used to put up game and as retrievers for land birds and for waterfowl, as hawking ‘on the river’ was a favourite amusement. They were also used as setters to assist in taking partridges and quail with nets.

The Elizabethan writer, Edward Topsell, describes ‘water spagnels’ being used to hunt otters and depicts a beast clipped like a poodle so that it might ‘be the less annoyed in swimming’ – and poodle, spaniel and retriever may all dispute it as an ancestor. (The clipped animal that appears in so many of Dürer’s woodcuts, however, is clearly a poodle.)

That great 14th-century sportsman, Gaston, Comte de Foix, author of the finest medieval hunting book, described spaniels as faithful, affectionate and fond of going ‘before their maistre and playeng with their taile’, but he must have suffered from some particularly exuberant member of the breed, for he complains that, if you are taking your greyhounds for a walk and have a spaniel with you, he will chase geese, cattle or horses, and the greyhounds through ‘his eggyng’ will attack too, and thus he is responsible for ‘al the ryot and al the harm’.

He further declares that out hunting spaniels are fighters and put the hounds off the line, which is manifestly unfair as they were never intended for hunting. But Gaston was a fanatical Nimrod and devoted to his running hounds. Duke Charles of Orleans, on the other hand, wrote poems to his favourite spaniel, ‘Briquet of the drooping ears’ (Briquet aux pendantes oreilles) – a charming one in praise of his field prowess and enthusiasm, and another beginning: ‘Let Baude range the bushes, old Briquet takes his rest ... an old fellow can do but little’, which sounds the sadder note of the true dog-lover’s affection for his ageing servant.

The most fashionable sport of the time was stag-hunting, and for this both greyhounds and ‘running hounds’ (also termed ‘raches') were used, often together, the greyhounds being slipped to stop the game quickly, or put in as relays to the pack, or, in the great battues sometimes organised for visiting notables, to turn back driven deer to the archers.

The truly serious huntsman, however, liked best to watch the running hounds work alone, for greyhounds and alaunts, says Gaston de Foix, finish the job too quickly but the ‘raches’ must ‘hunt al the day questyng and makyng gret melody in their lan-gage and saying gret villeny and chydeng the beest that thei enchace’. These dogs were rather like modern bloodhounds and a little like the type of hounds used for ‘still’ hunting – heavily built with powerful fore-quarters and short-muzzled heavy heads.

Wide colour ranges were permissable in a pack, earlier taste running to white, black and white, or mottled, while the late Middle Ages preferred tawny brown. Coats were usually smooth, though rough-haired specimens might be found, or even smooth ones with long-haired tails. Although all sorts of animals besides the stag were hunted, the hounds used differed more by training than by breed.

Harthounds, however, were generally larger and faster than harriers, which were all-round beasts so called because they ‘harried’ the quarry (not because they were restricted to hares). Selected dogs, hand-picked for scent, staunchness, and possibly size, were trained as ‘limers’, that is, they hunted on leash and were used to find, or ‘harbour’, the stag, and later in the hunt to untangle the line if the pack should be at fault, but these were individual specialists and not a distinct breed.

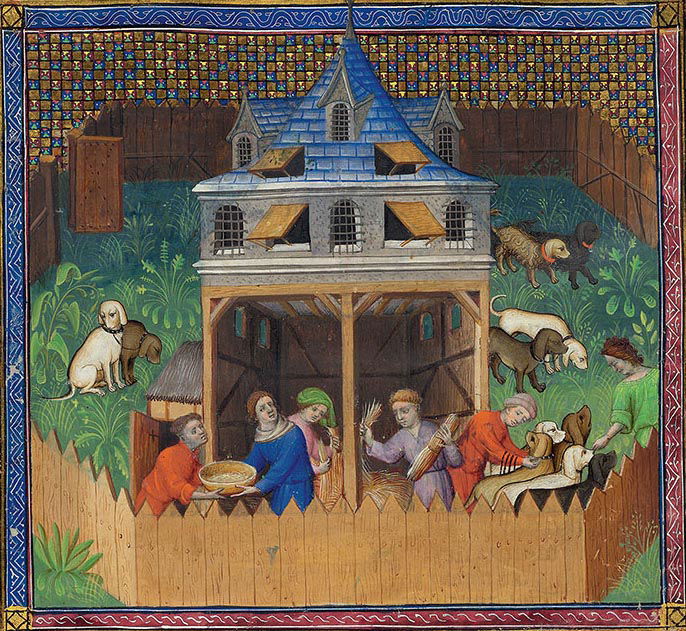

These animals, with the working greyhounds, were excellently cared for. Wealthy owners set up astonishingly high standards of kennel management, described in careful detail in Gaston de Foix’s ‘Traité de la Chasse’. The kennel where the hounds sleep, he says, should be built of wood a foot clear of the ground, with a loft for greater coolness in summer and warmth in winter, and it should also have a chimney to warm the occupants when they are cold or wet.

It should be enclosed in a sunny yard, and the door should be left open so that ‘the houndes may go withoute to play when them liketh for it is grete likyng for the houndes whan thei may goon in and out at their lust’ – as every dog lover knows. Hounds should be taken for a walk once or twice a day and allowed to run and play ‘in a fair medow in the sun’, and must be taken to a spot where they may eat grass to heal themselves if they are sick.

The kennel is to be cleaned every morning and the floor thickly strewn with straw, renewed daily. The hounds are to be given fresh water twice a day and rubbed down with straw each morning. The staple food is bran bread, with meat from the chase, and game to be killed specially for them even out of the regular hunting season. Sick hounds may be given more fancy diets, such as goat’s milk, bean broth, chopped meat, or buttered eggs.

Most of the kennel chores were performed by a dog-boy, an embryo huntsman who was expected to start learning his trade at the age of about seven and who, in addition to his other duties, had to learn the names and colours of the hounds and how to spin horsehair for their couplings. Besides this, he or some other child must be constantly in the kennel to prevent fights, even at night. In addition, it is laid down, in the uncompromising fashion of the age, that he should love his master and the hounds, and, furthermore, that he should be beaten if he fails to do as he is told.

These old-time hunting dogs reached a high degree of training, but the methods used must have been something of a trade secret, for not much is divulged – far less than was written on how to train hawks. Gaston de Foix says, indeed, that ‘a hounde will lerne as a man al that a man wil teche hym’, but, apart from the rather obvious maxim that pupils should be rewarded for doing well and punished for mistakes, he gives away little. He lays down that you must never tell your hounds anything but the strict truth. One should not talk to them too much, but when one does it should be ‘in the most beautiful and gracious language that he can’.

‘And by my faith,’ he adds, ‘I speak to my hounds as I would to a man ... and they understand me and do as I wish better than any man of my household, but I do not think that any other man can make them do as I do, nor peradventure will anyone do it more when I am dead’ – but then, Gaston believed firmly that things were not as they had been in the old days. Whatever the means, hounds were trained to obey a wide variety of notes on the horn as well as a number of different calls and terms, and they were encouraged by name; in fact, examples are given of typical names, such as Beaumont, Latimer, Prince and Saracen.

Considerable attention was bestowed on the medical care of canine ailments. Many of the treatments would startle a 20th-century veterinarian, yet they generally exhibit more common sense and less superstition than was currently applied to human sickness. Indeed, Gaston de Foix shows a critical faculty rare in his day when he states that making nine waves pass over a suspected rabies victim ‘is but litel helpe’. He discusses madness at some length, and nine kinds are listed, some held to be non-contagious.

He recommends that a suspected case be quarantined for four days to discover whether or not is is in fact madness. No kind of madness is regarded as curable, but prompt treatment of the bite of a mad dog might prevent its development. Nearly as much space is devoted to various types of so-called ‘mange’, and some remarkable salves are described.

There are detailed instructions on the care of injuries, including the splinting of broken bones, and Gaston’s English translator, the Duke of York, who was Master of Game to Henry IV, winds up with this exhortation: ‘God forbid that for a little labour or cost of this medicine, man should see his good kind hound perish, that before hath made him so many comfortable disports at divers times in hunting.’

In view of the medieval habit of attributing moral qualities and moral responsibilities to animals, it is not surprising to find that dogs sometimes received some of the benefits of religion. It is recorded that one Duke of Orleans had masses said for his dogs; and there was, of course, the famous messe des chiens on St Hubert’s day, a custom which still survives. Certain hounds of Charles VI of France which fell ill were sent on a pilgrimage to hear mass at St Mesmer in order that they might recover.

There was even once a dog saint; near Lyon a greyhound was said to have killed a dangerous serpent attacking his master’s child and, like the mythical Gelert, was himself slain on suspicion when the child could not be found. Afterwards his remorseful master buried him honourably beneath a cairn of stones where trees were planted in his memory. Later the dog was revered as St Greyhound, or St Guinefort, and rites were held at the grave for sickly children suspected of being changelings. Before long, of course, the ecclesiastical authorities caught up with St Greyhound and the grave was destroyed.

All in all, it is plain that modern dog-lovers should not be too self-satisfied over their advances in the care and handling of their pets, nor need dog-haters rage at the rising menace of the dog cult. None of it is new. Long ago, even in a rugged and often brutal era, men loved and trained and cherished an enormous number of dogs.

Weird as these beasts may look by Kennel Club standards, their owners recognised and surrendered to their essential dogginess, engagingly the same, whether in snub-nosed Briquet or this year’s ‘Best-in-Show’. From the boy with the mongrel to the champion’s master, what dog-owner does not echo Gaston de Foix’s five-centuries-old plaint that ‘the moost defaute of houndes is that thei lyven not longe inowe’?

This article originally appeared in the February 1979 issue of History Today with the title ‘The Dogs of Yesteryear’.