The Invention of the Flapper

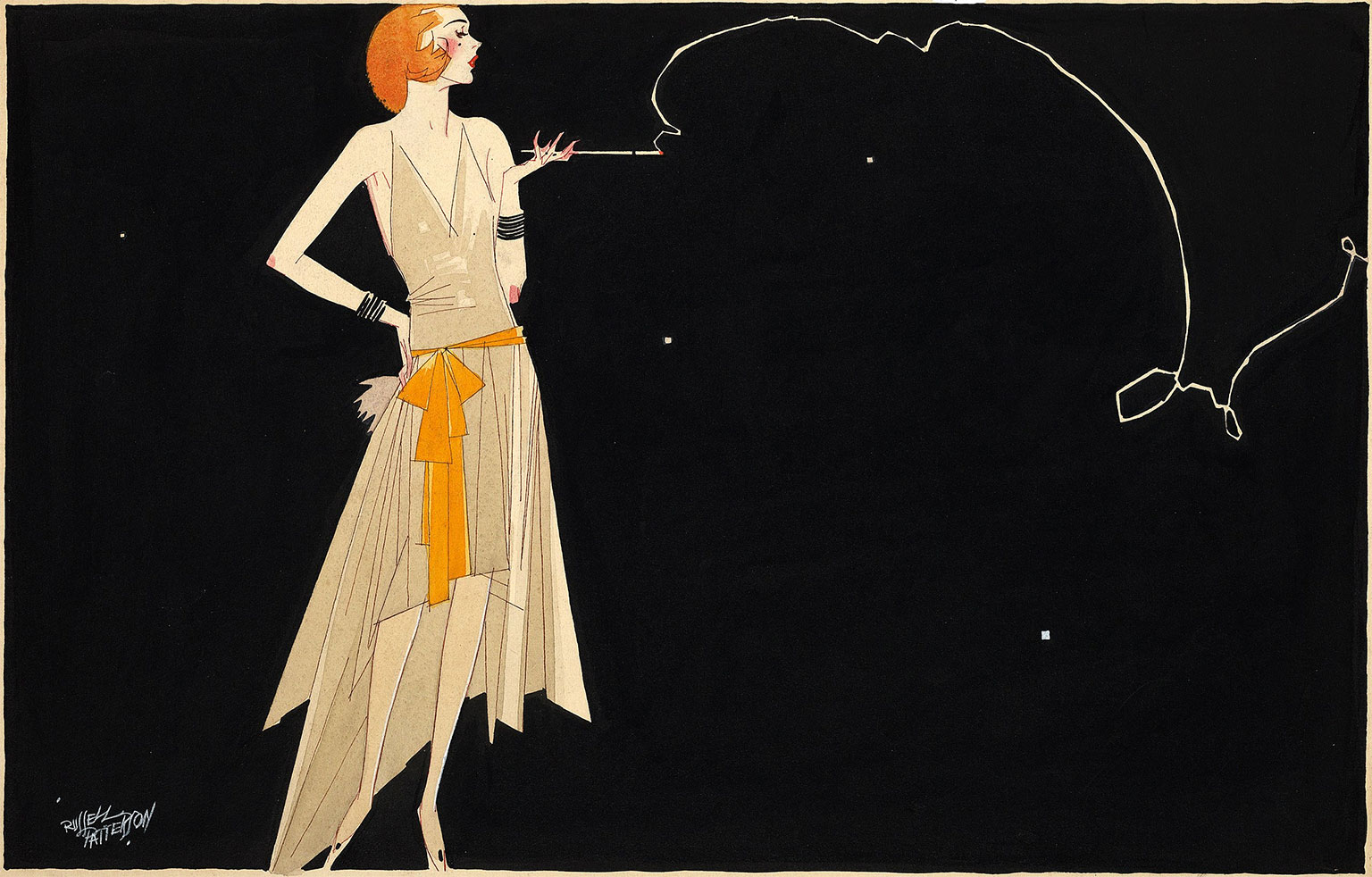

More than a symbol of decadence, the flapper should be seen as a quest by women for agency, independence and escape from domesticity.

The flapper continues to exert a powerful hold on our collective imagination. A symbol of decadence, ebullience and cynicism, she signifies at once the character of a decade – the 1920s – and the rebellion of a gender. Her genesis is often assumed to be the material deprivations and emotional disruptions of the First World War. Yet, as Linda Simon argues in this deftly written and meticulously researched cultural and experiential history, the flapper had a longer, complex and far more troubled evolution.

The flapper continues to exert a powerful hold on our collective imagination. A symbol of decadence, ebullience and cynicism, she signifies at once the character of a decade – the 1920s – and the rebellion of a gender. Her genesis is often assumed to be the material deprivations and emotional disruptions of the First World War. Yet, as Linda Simon argues in this deftly written and meticulously researched cultural and experiential history, the flapper had a longer, complex and far more troubled evolution.

For Simon, the flapper’s story begins in 1890s Britain and America. This is justified both etymologically – the word was used in this decade to refer to child prostitutes – and historically, the period generating numerous, interrelated social anxieties, which alighted on the body of the female adolescent. Eugenic concerns over racial degeneration, combined with women’s incursions into higher education and male-coded professions, raised fears of race suicide on both sides of the Atlantic. A ‘brain famine’ among the next generation could only be forestalled, it was argued, if girls eschewed the freedoms of the bicycling, smoking and studious New Woman and re-embraced their biological destiny of motherhood.

That these voices remained powerful determinants of girls’ lives is clear. The book provides fresh, insightful readings of didactic texts, ranging from G. Stanley Hall’s psychological treatise Adolescence (1904) to the newspaper advice columns of romance writer Laura Jean Libbey. Yet, as the 20th century progressed, alternative cultural productions offered less critical, more celebratory representations of the ‘modern girl’.

In the new movie theatres, films such as The Perils of Pauline (1914) featured young women living independently, escaping danger and outwitting villainous men, even if the plots’ denouement was often marriage. The explosion of dance halls provided real-life girls, their hair newly bobbed, with spaces in which to enact their own tentative rebellions. Emboldened by new role models, such as dancer Irene Castle and movie star Clara Bow, they sought to navigate the treacherous terrain of adolescent female sexuality, abandoning themselves to the rhythms of the turkey trot and grizzly bear as the nations’ moral overseers looked on with ill-disguised anxiety.

The book’s title alludes to the Lost Boys of J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan. Faced with the choice of Wendy’s maternal domesticity or the escapades of Pan’s perpetually youthful co-conspirators (played, at Barrie’s insistence, by young, attractive girls), flappers chose the latter. However, while tangible gains were made in sex education and self-expression as well as women’s suffrage, Simon makes clear that the flappers’ quest for agency, influence and new opportunities remained, at times, ‘as chimerical as Neverland’.

Lost Girls: The Invention of the Flapper

Linda Simon

Reaktion Books 298pp £14.99

Tanya Cheadle is Lecturer in History at the University of Glasgow.