It's Not Just Cricket

Did the British Empire have a culture?

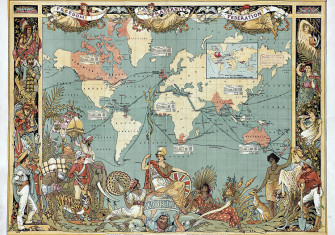

Like so much else, the modern idea of culture is an invention of the Victorians. In fact, they invented it more than once. Poet Matthew Arnold famously opted for an elitist definition – ‘the best that has been thought and known’ – because he feared the flattening and dehumanising effects of mass society. At the other extreme, anthropologist Edward Tylor saw culture in capacious terms which aimed at description rather than judgement: ‘That complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, law, morals, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.’ The difference, of course, was partly a function of perspective. Arnold was looking inward, to the rising tide of political democracy and mass production in industrial Britain, while Tylor cast his gaze overseas, to the bewildering array of places and peoples encompassed by the British Empire.

John MacKenzie has long challenged historians to weave ‘domestic’ and ‘imperial’ strands into a single tapestry. Through his own scholarship and his founding of the storied Studies in Imperialism series published by Manchester University Press, he has done as much as anyone to demonstrate that British history is always, at least partly, the history of empire. So there is good reason to consider his answer to some perplexing questions. Did the British Empire have a culture? If so, how can its history be written without sprawling into Tylorian infinitude? It is a daunting challenge. What used to be called the ‘new cultural history’ – encompassing the stories people tell to make sense of their world – is, if anything, more expansive than what Tylor had in mind.

MacKenzie’s introduction, referring to ‘cultural exports’ and ‘catalysts of conformity’, does not illuminate his chosen conceptual boundaries as clearly as it might. But what becomes evident over the course of the book is that he is interested in something like the imperial equivalent of cultural diplomacy: the forms and practices that proclaimed British authority, represented Britishness in appealing ways and constructed imagined communities stretching from Calgary to Cape Town to Calcutta. Before the British Council, in other words, there was the British Empire. That is not to say that MacKenzie is concerned exclusively with state-sponsored propaganda. Rather, he brings together the rituals and performances, networks and associations, images and media, that both accompanied Britons overseas and flattered their sense of civilisational superiority. This is a history of the soft power that always held the greatest allure for white settlers but also, in unpredictable ways, opened the door to participation by other subjects of empire.

MacKenzie is at his best in drawing out the ironies and skewering the pretensions of cultural imperialism. The most bombastic expressions of British greatness often drew on indigenous models, came under fire from opponents of empire, or proved more embarrassing than impressive. Held to celebrate Queen Victoria’s accession as Empress of India in 1877, the grand Delhi durbar (a Persian word for a Mughal tradition) was derided by British observers as a tacky boondoggle. Three decades later, a Victoria statue on the maidan in Lahore was tarred and fractured by protesters, inaugurating decades of nationalist attacks on the bloated and expensive sculptures Raj administrators loved to commission. The so-called ‘Empire Cruise’, consisting of half a dozen Royal Navy cruisers which steamed from port to port in 1923-24, simultaneously dazzled onlookers, raised questions about government spending and afforded the opportunity for more than 100 sailors to desert for a better life in Australia and New Zealand.

A recurring theme is the co-optation of cultural forms by imperial subjects who refused to conform to the passive role in which they were cast. While equestrian sports such as polo, a traditionally aristocratic diversion, remained the province of the elite, team sports such as cricket were embraced by Indian, West Indian and Aboriginal players. The Boy Scout movement flourished among Black Africans despite founder Robert Baden-Powell’s unyielding commitment to racial hierarchy. The gaze of photography, long used to chronicle stereotypical and often salacious scenes of primitivism, was reversed in the hands of little-known figures like Mungo Murray Chisuse, a Malawian who photographed anticolonial leader John Chilembwe in poses of striking dignity.

‘In some respects’, MacKenzie claims, things like sports, newspapers and entertainment ‘remain the major legacies of empire in North America, the Caribbean, Africa, Asia, and Australasia’. At a time when historians are turning ever more intently to imperial histories of violence, dispossession, resource extraction, legal authoritarianism, territorial division and ethnic conflict, this assertion can be read as either refreshingly counterintuitive or bafflingly out of touch, depending on your point of view. But even for historians attuned to the significance of culture, the selection principle MacKenzie employs is too hazily defined to make a convincing case. Why statues and not architecture? Why racing clubs and not scientific societies? What about food, music, design and fashion? What, for that matter, about education, religion and medicine? Far too much is left out. The effect is rather more like rummaging through an attic. So many of the artefacts MacKenzie examines – the gigantic statues, the grand-manner canvases, the magic-lantern shows – felt anachronistic even when they were new.

There can be no doubt that empires exercised soft power as well as hard: the iron fist in the velvet glove. But that power was probably least effective when it was most self-consciously monumental and spectacular. Cultural history which strips out the everyday cultures of homes, schools, churches, factories, hospitals and restaurants — the unglamorous but ubiquitous sites of cultural transmission — risks ending with a cabinet of curiosities.

A Cultural History of the British Empire

John M. MacKenzie

Yale University Press, 432pp, £25

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Erik Linstrum’s latest book is Age of Emergency: Living With Violence at the End of the British Empire (Oxford University Press, 2023).