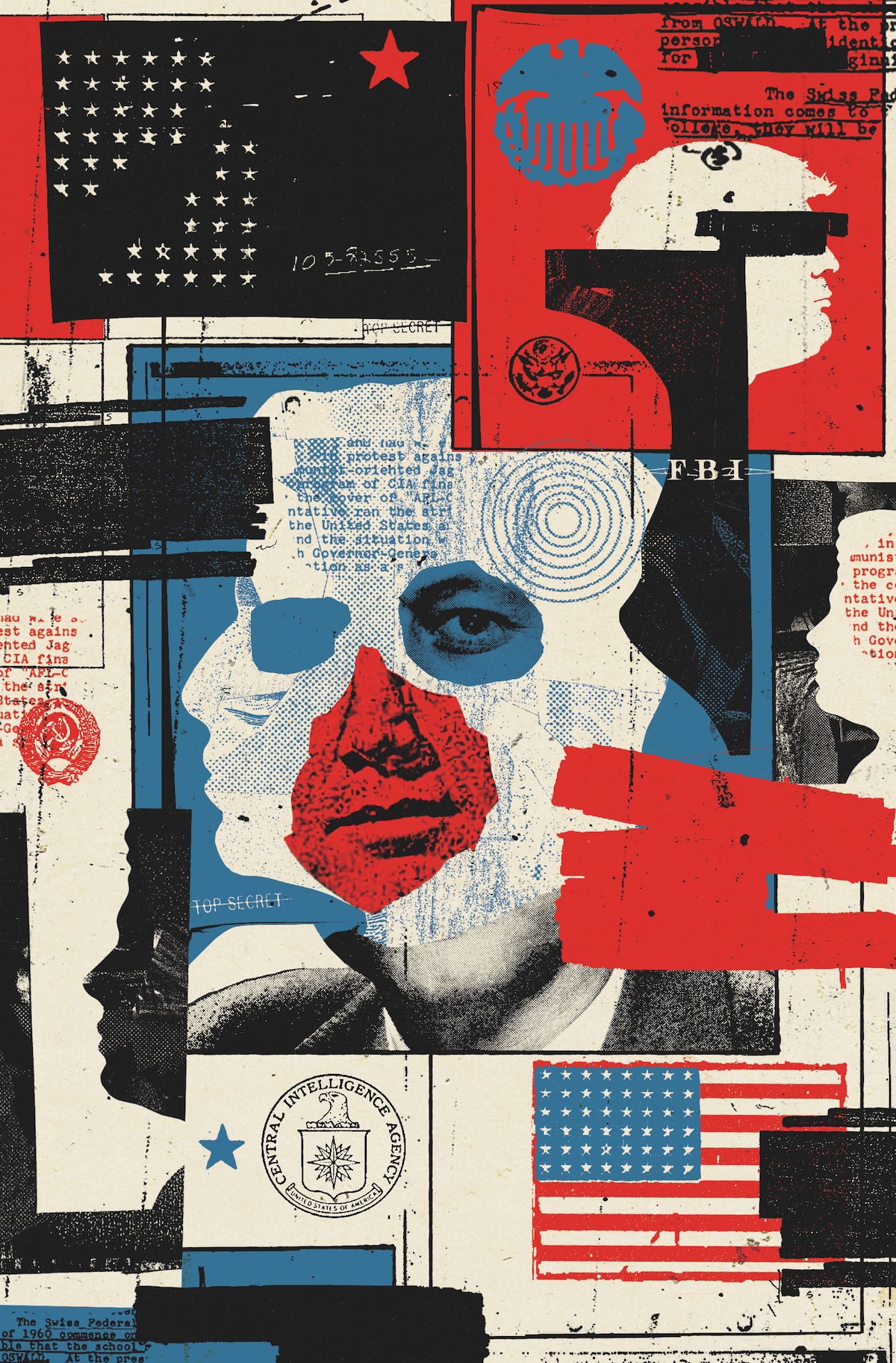

Lost in the Kennedy Files

The release of government documents related to the Kennedy assassination will keep scholars busy for years, but will we learn anything new?

On 18 March 2025 the US government began to make good on Donald Trump’s promise to release all federal records related to the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, his brother Robert, and Martin Luther King. ‘People have been waiting decades for this’, Trump said on the day of the files’ release; as a biographer of both Kennedy and King, I was among them. But although the decision to make the files public is intriguing, it should also be regarded with a dose of cynicism: if JFK was killed by the CIA in an elaborate plot that used Lee Harvey Oswald as a distraction and allowed the actual hitman to escape, would the same personnel be likely to meticulously preserve evidence of their guilt?