Remembering South Vietnam

With North Vietnam’s victory in 1975, its southern counterpart ceased to exist. What happened to South Vietnam?

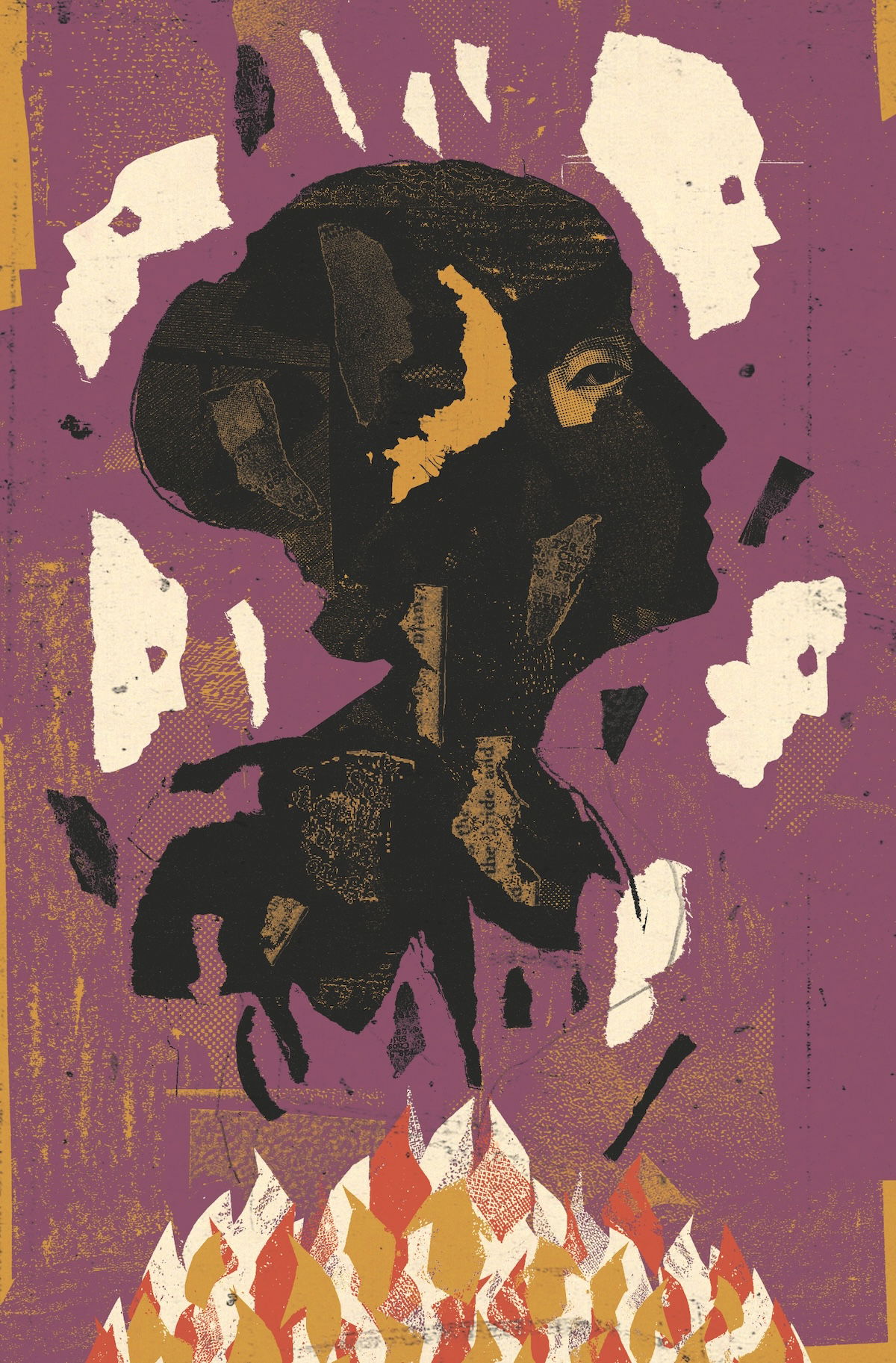

In her 2010 memoir Tales from a Mountain City, Quynh Dao – who was 15 at the fall of Saigon in 1975 – describes returning to Dalat, a city in Vietnam’s Central Highlands, at the end of the war. The North Vietnamese Army (NVA) had looted her family’s home and made bonfires of their books and magazines:

There were hundreds of issues of Life magazine, Paris-Match, Reader’s Digest, father’s lifetime collection of books, the comics we children read … the simmering fire devoured the pages slowly, surely, from the edges of the pages to the spines.

A few weeks later, the NVA evicted Dao’s family. Escaping Vietnam by boat in 1979, Dao fled to a refugee camp in Malaysia, and then to Australia as one of millions of ‘boat people’. By then, South Vietnam, the country in which she had been born and raised, no longer existed.