Pox and Paranoia in Renaissance Europe

J.S. Cummins considers the impact of syphilis on the 16th-century world – a tale of rapid spread, guilt, scapegoats and wonder-cures, with an uncomfortable modern resonance.

Pliny the Elder noted that exploration, expansion and empire brought problems as well as novelties in their wake and, discussing new diseases in particular (Natural History), he commented on one complaint brought home by a Roman knight after service in Asia Minor. This, a scaly facial eruption, jokingly called 'Chin Gout' (Mentagra) by those not afflicted with it, puzzled Pliny, not least because it chose its victims from one special stratum of society: women and the lower orders were immune, noblemen alone suffered from it. He concluded this must be because of their custom of kissing each other in greeting. 'Chin Gout' required drastic measures: the flesh was burnt down to the bone with caustic which left a scar almost as disfiguring as the disease itself. Pliny began to wonder what could have so angered the gods as to make them want to add one more to the three hundred diseases already afflicting humanity.

Contact with the East, then, had its dangers, but so too had contact with the West. In the sixteenth century European-borne diseases contributed to the collapse of the two great Amerindian civilisations. The effects of smallpox alone in early America have been compared to those of the Black Death in Europe, for the genetically-virgin peoples of the vast and hitherto isolated continent of the New World were helpless before the invaders' viruses.

America, however, exacted revenge for the invasion of the western paradise. The New Eden had a serpent too, and Columbus brought home more than treasure: 'There were', wrote Fallopius, 'aloes hidden in that honey'. The Europeans who took smallpox into the New World brought home the great pox, syphilis, the only disease to be named after a Renaissance Latin poem.

Most medical historians agree on the New World origin of the virus which, like 'America', has a dateable beginning, for it appeared in Europe when Columbus returned from his first voyage (1493). Although the thesis fits the chronology, not everyone accepts it. Yet three separate, independent, reliable and contemporary authorities declared the disease was American: Fernandez de Oviedo, a pioneer in the New World and official chronicler of the Indies; Friar Bartolome de Las Casas, a missionary veteran; and Dr Ruy Diaz de Isla, the celebrated specialist. Las Casas for example states roundly:

I repeatedly questioned the natives who confirmed that the disease was endemic in Hispaniola. And there is plenty of evidence that any Spaniard who was unchaste while there caught the infection: indeed scarcely one in a hundred escaped its terrible and continual torments.

Columbus, it is true, declared that his crew returned to Spain 'wonderfully fit and healthy'. But he was writing for the pious eyes of his patron, Queen Isabel, and all his early reports read like tourist promotion literature: it was not his purpose to draw attention to the aloes; all must be honey. In any case, his ship the Nina was not the only vessel to return, and Ruy Diaz de Isla gives evidence that he was called to attend victims on board the second ship, the Pinta (one of whose pilots died soon after arrival), and that he witnessed the spread of the disease in Barcelona, where it caused a wave of public prayers and penances.

Moreover, Las Casas also points to the six natives brought to Spain by Columbus from that first voyage. Las Casas believed that these innocent carriers of the germ helped to spread the infection probably by frequenting Spanish prostitutes, some of whom were camp-followers of the forces raised by the French king, Charles VIII, for his attack on Naples in the following year. These mercenaries, in turn, spread the virus across Italy and later still carried it back along their lines of retreat, sowing the scourge widely across Europe where it propagated itself in geometrical rather than arithmetical progression.

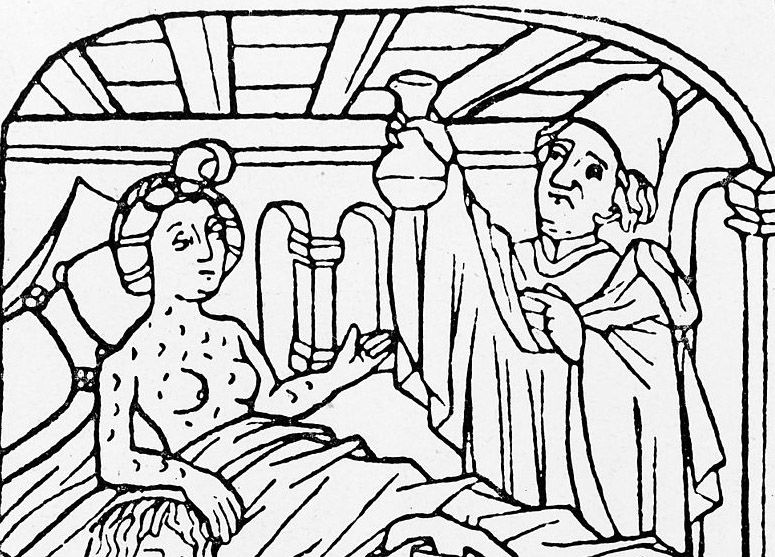

There are, of course, no reliable contemporary statistics to show the initially explosive spread of the epidemic in the West where, as a new virus, it encountered no natural innoculation in the bodies it invaded. Although its overall demographic effect was not very great, its loathsome and conspicuous symptoms (chancres, pustules, skin eruptions, leg ulcers) caused alarm. In its later tertiary stage it could lead to madness and death (often by a blow-out of the aorta, the main artery leading from the heart). The most frightening and lurid account of these early symptoms is to be found in the Libellus Josephi Grunpecki (1503); this, one of the most terrible texts we have from the period, is the work of a German canon who caught the infection in Italy.

However, by the end of the century the earlier, fulminant form of the disease yielded to milder strains, displaying less florid symptoms; and at the same time natural resistance to the organism increased in the affected populations.

The aloes in the American honey were a profound shock; but not everyone was surprised, for certain astronomical phenomena in 1484 had alerted some observers. One such was the physician Paulus von Middelburg, who predicted the coming of a 'terrible venereal disease' in that same year. He, however, may simply have felt a natural apprehension based on his professional experience since he practised in Rome where there were 'more prostitutes than there were philosophers in ancient Greece or friars in modern Venice'.

After Spain and Italy, the disease was recorded in France, Germany and Switzerland (1495); in England, Holland and Greece (1496); the Middle East and India (1498), Hungary and Russia (1499). Its appearance coincided with the great voyages of exploration when, for the first time since Adam, almost all the human race came into contact. Consequently it spread world-wide from the Caribbean to the China Sea and as rapidly as man could travel. Within a decade after Columbus' return an outbreak of syphilis was reported in Canton.

In those first decades the violence of the disease was such that in the popular mind it replaced the medieval plague and the symptoms were so frightening that the very lepers refused to live near syphilitics. Raging 'like flame in stubble', the sickness ravaged Christendom, sparing neither the great nor the good, striking at emperors, kings and cardinals. It influenced inheritance, succession, dynasty; it made Muslim martyrs and Christian saints (fear of it kept Francis Xavier a virgin amidst the temptations of Paris university life); it gave a boost to Platonic love theories, which became a social cult, strengthening in maidens that coldness lamented in verse by spurned (though perhaps secretly relieved) lovers. The carefree call to 'gather ye rosebuds' was suddenly offset by the urgent warning 'memento mori'. In Spain the new awareness contributed to the resurgence of the death theme in sixteenth-century literature. The sickness, according to some, touched English national affairs, although Samuel Pepys, accused of saying 'Our Religion came out of Henry the eighth's codpiece', would not have meant the same as those who see a connection between syphilis and Henry's more bizarre behaviour (in fact, the assumption of the king's syphilis though not unreasonable cannot be proved).

William McNeill (in Plagues and Peoples), linking plague and the decline of Spain, also suggests that the political decline of Valois France (1559-89) and of Ottoman Turkey (after 1566) may have been related to syphilis in the respective reigning families.

The new venereal plague affected social life. Public bath-houses almost disappeared (leading to lower standards of personal hygiene), the common drinking-cup and easy kissing fell from favour; mistrust made friends and lovers nervous of each other and More's Utopians urged engaged couples to inspect each other's nakedness and not to risk dying of ignorance: 'when buying a horse you make sure there are no sores beneath its saddle'.

The syphilis which accompanied Europeans to East Asia followed the same pattern there as in the West: after upsetting the insouciant sex-life of Ming China it conveniently carried off four troublesome enemies of Tokugawa Ieyesu ('the maker of modern Japan') who, lucky as always, had even the spirochaete on his side, favouring his political ambitions.

In time the virus was carried back to the New World. Twenty-six years after the landing of the Mayflower it was recorded in the north, having already been carried by the Portuguese to Brazil which (said the late Gilberto Freyre) was 'syphilized before being civilized'. Later travellers there, seeing even monasteries and nunneries 'devasted' by it came to regard Brazil as the land of syphilis par excellence. By the nineteenth century it had become so common there as to arouse neither fear nor shame; looked upon as a family ailment, akin to whooping cough or measles, syphilis became almost a rite of passage into manhood and young Brazilians exhibited their scars like war-wounds. This had happened earlier in Spain, for inevitably fear of the disease receded as its initial virulence decreased in the later sixteenth century. Already in 1558, Archbishop Carranza complained that 'a man no longer loses his honour or authority by getting this leprosy. Rather it is become so fashionable that not a man at court but must exert himself to get it'. Later still, Pepys remarked of Charles II's court that 'the pox here is as common as eating and swearing'.

But in the beginning things were very different. Initially the new disease inspired the typical reactions to any threat of a major epidemic: fear, panic, hysteria; and these always demand scapegoats – usually some minority group. Often this was a signal for an outburst of anti-semitism. Syphilis, however, was unique. No particular minority was blamed for its appearance, rather, in an age of incipient nationalism entire races were judged to be the culprits. Syphilis, a novel phenomenon without any name of its own, was, in each instance, called after those associated with its appearance. Because of its coincidence with the French invasion of Naples it became known in Italy as 'the French disease'. For chauvinistic reasons this nickname was widely adopted, except by the French for whom it was the 'Neapolitan evil'. The Spanish welcomed the name as absolving them of guilt; the Dutch, claiming that the virus reached the Low Countries in 1496 in the train of the Spanish Princess Juana, bride of Philip the Handsome, called it 'the Spanish Pox' (Erasmus's scabies hispanica). In Central Asia beyond the Urals it was 'Russian'; in the East Indies, East Asia and Japan, the 'Portuguese disease'. The latter themselves called it either the 'French Pox' or 'St Job's sickness'. There were also some elegant variations: 'plum-blossom sores' (Ming China); 'Monseer Drybone' or the 'American disease' (England); 'Brandpis' (fire-piss), a Dutch alternative, suggests a possible double-meaning for Francis Beaumont's Knight of the Burning Pestle. The Spanish had other names, too: 'las bubas' (blains), from the Greek, but perhaps suggested by the bobas, those serpents which sometimes fell from trees and strangled unwary New World travellers; 'la gota', a generic term for arthritis and rheumatism, also served as a euphemism for syphilis. Classical scholars had their own word, mentulagra ('prick gout') by analogy with Pliny's mentagra ('chin gout'). The Irish, for once missing a trick, failed to blame the English for the new disease which they called bolgach fhrancach ('French pox"). It is not known when the disease reached Ireland for, as the Irish medical commissioner Sir William Wilde (Oscar's father) reported in the 1851 census, 'the moral guilt attaching to it prevents any gathering of detailed information or accurate statistics". (The first printed reference to it in Ireland comes in 1681, although there are earlier manuscript recordings.)

Syphilis appeared in European literature both as a medical phenomenon and as the subject of a celebrated neo-Latin poem of three thousand hexameters (1530) which gave the disease its definitive name. Its author, Girolamo Fracastoro, was the ideal Renaissance man: poet, humanist, logician, geologist (Humbolt ranks him with Leonardo as being ahead of his time), geographer (to whom Ramusio dedicated a volume), and student of extra-sensory perception, he was also a successful physician whose patients included Paul III, Cardinal Pole and Vittoria Colonna. Amongst his friends were Bembo, Oviedo and Copernicus. His pioneer germ theory of disease, a landmark in the history of pathology, brought him honours: in his own time a mention in Orlando Furioso, and in ours a medical journal (Il Fracastoro) is named after him. He was outstanding amongst the estimated one hundred poets in the Rome of his day, where the arts flourished amidst religious and political storms. The reigning pope, Leo X, has not had a universally good press yet some think him lucky; Lord Acton told a distressed Cardinal Newman that 'a sincere article on his character would give the greatest offence'. Leo, however, was no pagan: busy though he was he always attended mass, and on occasions even celebrated it. Perhaps the last of the Renaissance popes to look on the papacy as primarily a temporal monarchy, he presided over a court of intellectual sybarites, who shuddered at the Vulgate with its irreducible smell of fishermen and shepherds.

Many Spaniards (Torres Naharro, Guevara, Valdes, Oviedo, Cano, Las Casas) were disgusted by the moral corruption of Rome, although earlier an estimated 10,000 of them, delighted by rumours of low prices and even lower morals, fled there to join their own Alexander VI, happy to escape the rising tide of religious earnestness – not to say fundamentalism – at home. One such was the Andalusian prostitute in Francisco Delicado's Lozana andaluza (1528) which gives an uninhibited view of the swarming low life of Rome, including two delightful catalogues of the resident prostitutes, their nationalities and different quirks and qualities.

Fracastoro, the poet, sought to avoid the usual tame repetitions of Ovidian formulas. He wanted a fresh theme and a new myth, and these he found for his Syphilis 'a divine poem by the most outstanding poet since Virgil' (Scaliger). Dedicated to his Venetian friend, Pietro Bembo, it is arguably the most famous of all Renaissance Latin poems. Yet he was not the first poet to treat the subject, for at least seven or eight others had already done so, including Sebastian Brant who published his De pestilentia scorra eulogium in Basle in 1496. Fracastoro, the physician intrigued by the new disease, and the poet seeking novel themes, was well placed in Rome, then a clearing house for geographical gossip and rumour. He could not, for instance, have avoided knowing Peter Martyr's Newsletters from the Indies (to which Leo X was so publicly addicted) and perhaps also saw the manuscript Latin poem, Itinerarium, of Alexander Geraldini, Bishop of Santo Domingo.

In the third, and last, book of his syphiliad, Fracastoro gives an allegorical description of the Spaniards' encounter with the New World. This relates the story of the sin and sickness of a young shepherd, Syphilus, 'the first victim of the disease and from whom it derived its name'. (Despite this, the poem itself has a double title: Syphilis, or the French Disease.)

Although at one point Fracastoro declares that this curse laid upon mankind 'is eternal and irrevocable' (III: 343), towards the end he shows his victim to be cured. In reality things were not as simple. At first the doctors were nonplussed, unlike the many quacks who rushed in, attracted by the rich rewards to be extracted from the afflicted.

Much sixteenth-century medical opinion is not worth the paper it is written on, but there was plenty of it between 1493-1600 when some 285 works dealing with the 'French pox' appeared. The doctors recommended all sorts of treatments and nostrums, according to their whims and fantasies. Prescriptions included raw China-root, cooked whore-flower buds, boiled vulture broth with sarsparilla, serpents' blood, and forced sweating (consequently violent exercise, ball-games, running, jumping, wrestling, boar-hunting, even ploughing, were enjoined). Other remedies were proposed: massage, smoking, avoidance of the south wind, abstinence from pork and peas, sex with a virgin negress, nor no sex at all. Mercury treatment (inunction, drinking, inhaling) enjoyed an early popularity, hence the saying 'Venus for a night, mercury for life'. By 1515, however, this 'quack-silver' cure lost ground to guaiacum, a newly discovered American wonder-drug, also called the holy wood, which was reckoned to be a sovereign remedy. Nicolas Monardes, the Sevillian doctor and botanist, relates how the holy wood was discovered and how it would cure a man of the disease 'provided he returne not to tumble in that same bosome where he took it firste'. Guaiacum, despite its diuretic and purgative effects, was of no therapeutic value whatever but it had much to recommend it. For example, it came from the same country (Haiti) as the disease it was thought to cure. This fitted in with the theories of the theologico-scientific doctrine of specifics: by analogy an American ailment required an American cure. (This also 'proved' that the virus came from the New World.) Guaiacum was soon making fortunes for importers such as the German banking family the Fugger. Introduced into Spain (1508), it was in use in Germany by 1519 and in Italy in 1528: Benvenuto Cellini claimed it brought him relief (natural remission of the disease in the first stage being often mistaken for a cure). Thomas Gale recommended it to the English in his Second Antidotarie (1563), and its popularity continued for decades: for example, Jose de Acosta, the missionary-naturalist, returned to Europe in 1587 on board a ship carrying 350 cwt of guaiacum as part of its cargo of American imports. And in the eighteenth century the great Dr Boerhave declared it 'reached the places that mercury could not reach.'

Meantime, the mal frances spread widely and wildly. At first some, like Erasmus, believed there could never be a cure, but by the end of the century, as its impact declined, optimism spread: 'in time', wrote Loys Le Roy (1575), 'this too will disappear as did [Pliny's] mentagra'. Yet if some doctors were nonplussed, others, as terrified as the lepers, fled from the victims. This was not always a tragic dereliction of duty perhaps, for some treatments tended to be drastic: on his own admission (1581) one army doctor had 'amputated 5,000 penises'. Spanish medical men enjoyed a high reputation as pioneer specialists and Ruy Diaz de Isla, who witnessed the arrival of the disease in Europe when he treated some of Columbus' men, was the greatest syphilographer of the time. In his Serpentine Malady (Seville, 1539) he 'guesstimated' that over a million people were infected in Europe. Himself a victim, he claimed to have treated some 20,000 patients in All Saints' Hospital, Lisbon.

His medical counterpart in England, William Clowes, reported (1579) that the disease was as rife there 'as in America or Naples': he claimed that in the city of London he had cured over 1,000 sufferers in St Bartholomew's Hospital alone. Convinced that ignorance kills but alarmed at his own temerity, he defended himself for publishing in the vernacular with a suitably sanctimonious 'Epistle to the Reader' of his Treatise. The disease, 'a notable testimonie of the just wrath of God and a staine upon the nation' was due to 'beastlie disordered rogues, vagabonds, and the many Alehouses'. He prayed the magistrates, 'God's second line of surgeons', to be a 'terrour to the wicked', and presumably also to the sick. (Clowes' use of the term morbus gallicus is the first recorded in England.)

No royal personage ever tested the king's touch on syphilitics and although Charles VIII had practised his powers in Naples in 1495 ('et sanavit plures Neapolitanos', says the chronicler) it was not done in order to cure the still unrecognised disease then emerging there. The institutional Church, however, made some effort to help, and soon 'the rituals of prophylaxis defined themselves', as McNeill puts it. The liturgy recognised the malady, even 'canonising' its nickname when a new mass (Missa contra morbum gallicum), with its gospel taken from St Luke, naturally, was inserted into the 1474 Roman Missal.

On a more popular level, new recruits were drafted into the ranks of the patron saints, those 'momentary gods' forming a special task-force of advocates for particular crises (for example St Blaise, against sore throats; St Boniface against threats of sodomy). Prostitutes, now a suddenly endangered species, fearing that their own St Mary Magdalen could not alone cope with such an epidemic, elected a second protectress: St Nefissa, 'who had given herself out of charity'; and in time, St Denis and St Job became the advocates against the French disease.

Since many hospitals refused to admit syphilitics, some devout laymen sought to respond to the crisis. Just as during the Black Death the friars devoted themselves to the care of the sick, so now pious groups opened special hospices, the first in Genoa in 1497. This movement spread, particularly after the foundation of the Oratorians of the Divine Love (1515), a religious order dedicated to nursing. A number of specialist hospitals opened in Spain, an early example being the Hospital Real in Granada whose charter stipulated that it was for the 'treatment of no other disease' but syphilis. One of the first venereal disease clinics in the New World was the Amor de Dios hospital in Mexico City. Similar foundations spread later to the missions in the Philippines and Japan where the Franciscans distinguished themselves as nurses, to the edification of the locals and the distress of their Jesuit colleagues who felt such work degraded the missionary. (Some scrupulous priests were troubled by the dangers inherent in medical work and St Vincent de Paul warned them against taking the pulse of any dying woman, young or old, for fear the devil would use the opportunity to tempt them. This of course was simply a spiritual version of the fears of some contemporary doctors who are alleged to be afraid to touch certain patients.)

In the beginning, the relationship between syphilis and sexual activity was not always recognised, even though a significant number of soldiers in the French army at Naples had complained of tumours in their private parts. Instead, the disease was first attributed to events in outer space: specifically, the conjunction of Mars, Jupiter and Saturn in Scorpio, which was thought to preside over the genital sphere. However, once the connection was made, the moralists rushed in as eagerly as the quacks had done in the medical area. Naturally, in a pre-scientific age which still held to the punishment theory of disease, syphilis was perceived as a carnal scourge. (This may perhaps be equated with modern speculations, and even legal defence pleas, that see links between lead pollution and juvenile delinquency, or between junk-food and murder.)

Ludwick Fleck, in his 'philisophical' study of syphilis (1935), maintains that in all history no other disease was ever to the same extent regarded as the result of moral decay. Even leprosy, for all its highly emotive connotations, was seen more as a terrible fate than a directly retributive blow from Jehovah. The invocation of Nature to sanction the moral code is old: even unwitting sexual impropriety brought disease (Genesis XII), just as impiety brought meteorological disasters. And so syphilis was proclaimed by one Portuguese bishop to be 'the wound by which Heaven revenges itself'.

This equation of health and holiness led to the view of heresy as mental illness, and inquisitors, like William Clowes' London magistrates, then became soul-surgeons. In time syphilis itself became a metaphor, and Locke, thinking of despotism as peculiarly French, allegedly kept the first draft of his Two Treatises on Government between covers marked 'De morbo gallico'. The idea still survives and in America during the early 1920s, and again in the McCarthy years, Communism was presented as an infection brought in by immigrants.

By an extension of the doctrine of specifics and the theory of God's poetic justice, it was deemed appropriate that the sinner should be punished in that part of the body with which he had sinned: 'the part that suffers most, is the part that's most to blame' (la parte pecante es la parte paciente) as Lopez de Villalobos put it in his 'Poem on the Bubas' (1498). Roderick, last of the Spanish Goths, sentenced to solitary confinement for lust, was, according to the old ballads and Don Quixote, heard crying out, 'I am being eaten away in the part wherewith I sinned'. So too Charlemagne, said the Latin poet, paid for his sins when animals lacerated his private parts. And Bosch (for syphilis made its appearance in art – Durer, Bronzino – as well as in literature) shows a sinner's sexual organ turned into a snake – el mal serpentino – tearing open his own belly.

Reactions to the morbus gallicus epidemic were many and varied; some were to be expected, others less so. The epidemic is sometimes linked to the outbreak of the European witchcraze; to new thought-styles constructed out of the experience of the disease and the enquiry into its causes; to the social cult of Platonic love theories outlined in such works as the Dialoghi d'amore (Rome, 1535) of the Portuguese Jew Leon Hebreo (Judas Abravanel), and expounded by others. It is not overspeculative perhaps to see the disease as also introducing other developments, both trivial and sublime: in popular fashion and, however unconsciously, in new devotional trends.

If the sinful part of the body was to be the wounded part, there seems to have been a wish to safeguard that part and simultaneously to assert its health and. strength. The codpiece, which began modestly in the fifteenth century as a means of protecting the body, now during the Renaissance, developed into that exaggerated fashion which so puzzled Montaigne later. As if to offer reassurance by representing vigour and strength, the codpiece became a sort of psychological weapon, rejecting the neo-platonic solution of sublimation, and it gave a defiant even a bizarre riposte to the chilly warning being sounded everywhere. But in time it became absurd when it assumed the shape of a permanent erection.

Some corollary to this may be detected in the religious sphere, where that same preoccupation with man's newly-emphasised frailty is echoed not only in the liturgy and the 'corporal works of mercy' (for example, the new hospitals), but also in sermons and sacred iconography which alike reflect new tendencies. The emergence of 'incarnational theology' in the Renaissance, and the reassessment and redoubled interest in the mystery and meaning of certain aspects of Christ's life may be seen as a devotional reaction to the newly-enforced focus on the human body: the physicality of Christ, the 'word made flesh', was now commemorated and emphasised anew.

During the Black Death, many had sought succour and consolation from Jesus, the suffering Son, who was perceived as closer to wretched humankind than the awful figure of Almighty God, the father-judge. Similarly, some Renaissance preachers and artists now re-stated another aspect of the Passion, contemplating in particular the circumcision, the first of the five times when Christ shed blood as part of the divine plan for humanity's salvation. That feast was celebrated annually by the Church on January 1st, and the relic of the holy foreskin (subject of a sermon preached before Alexander VI in 1498) was venerated in the Lateran Basilica until its disappearance in the Sack of Rome (1527).

A link may also be detected between the new venereal plague and the sacred iconography studied in Leo Steinberg's The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art, where we are reminded that the humanisation of the Son of God, and the humanity of the suffering Christ must entail, along with his mortality, his assumption of sexuality. Hence Christ is now depicted as fully man, in all respects, and the representation of his genitalia is no mere naturalism but is invested with deeper meaning. Just as the Black Death made an impact on devotional trends in the fourteenth century, when preachers and pious writers emphasised the humanity of the suffering Christ, in much the same way these fresh emphases in the sixteenth century can be seen as a reaction to the new crisis: Jesus the Man, human, physical, virile, is presented to the faithful as an exemplar, prevailing over concupiscence through chastity. Sinners, now forcibly reminded of St Jerome's warning 'the power of the devil is in the loins', were also being reminded that supernatural help was available to them.

As in art, so too in sermons. Preaching at the papal court at this time exalted the Incarnation, stressing that the Jewish ceremony in Luke 2:21, the equivalent of Christian baptism, was a prefiguring of the Passion. Steinberg who, in his apparently outrageous thesis, offers these 'desperate raids upon the inexpressible' with all due delicacy, tact and sensitivity, sees this new focus in contemporary art and preaching as evidence of a 'serious and sustained theological concern with Christ's genitalia and, more specifically, of a Renaissance tendency to regard Christ's phallus as a symbol of power' (Andre Chastel), Such developments may well have been an unconscious response to the contemporary climate and part of the effort to come to terms with it.

In our own time penicillin was believed to have conquered syphilis and the disease was relegated to the archives of medical historians. In Barcelona, for example, in the appropriate city quarter, a wall-shrine to Alexander Fleming is regularly and gratefully decorated with floral tributes. This comfortable spectacle is somewhat disturbed however by recent reports of an American research team which is publishing evidence suggesting that Aids is a development of syphilis and that the old 'serpentine evil' still remains as a scourge of mankind. If proven, the theory would bolster the opinion of those who maintain that the appearance of the 'French evil' in 1493 was not the arrival of a hitherto unknown New World plague, but rather a variant strain of a disease as old as humanity itself.