‘The Heretic of Cacheu’ and ‘Worlds of Unfreedom’ review

The Heretic of Cacheu by Toby Green and Worlds of Unfreedom by Roquinaldo Ferreira, painstakingly recreate the worlds at the beginning and end of Portugal’s slave trade.

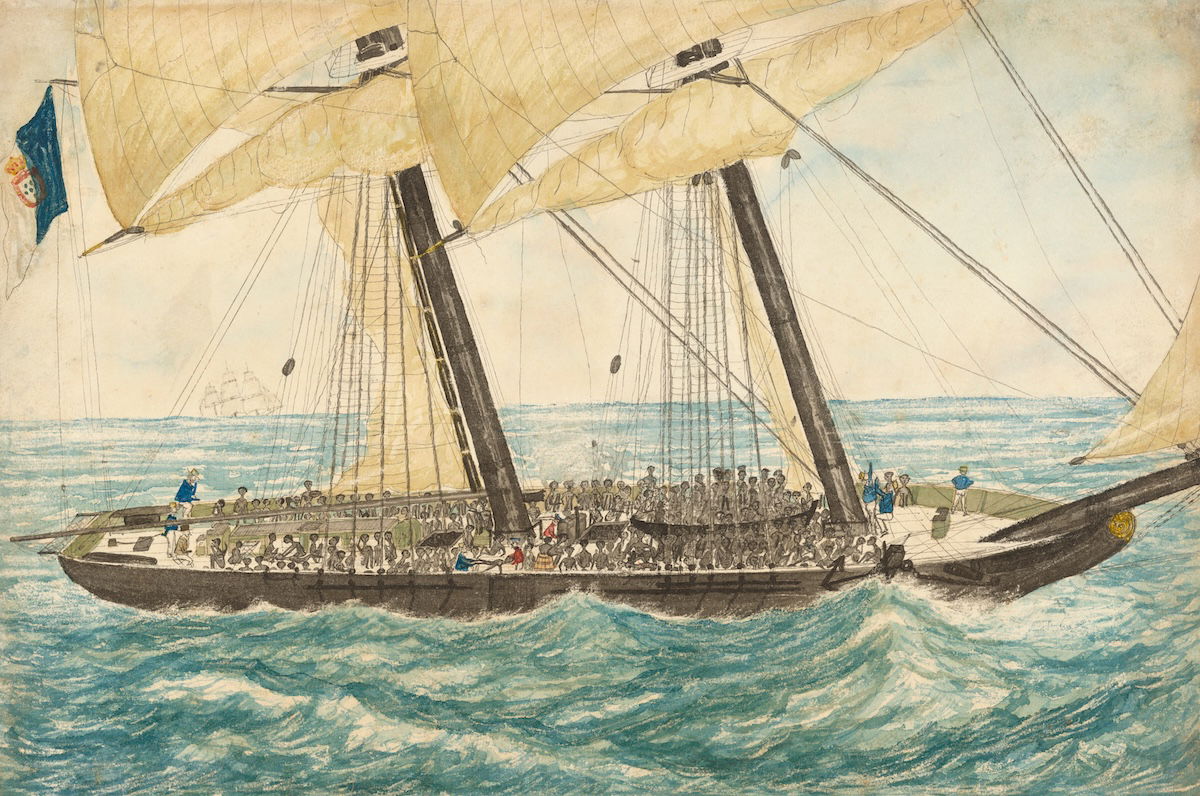

The Portuguese pioneered trans-Atlantic slavery, trafficking more people than any other nation and continuing to do so decades after Britain’s abolition of the trade in 1807. Yet the country’s first, long-promised, memorial to victims of slavery – Angolan artist Kiluanji Kia Henda’s ‘Plantation – Prosperity and Nightmare’ – only materialised in Lisbon in 2021. As is the case in other countries with a shameful history of involvement with the slave trade, discussions of that history can be contentious. ‘Those who question the narrative are called “woke” and face arguments such as “it was the British Empire that was racist, not ours”’, explained historian Pedro Cardim in 2023. The question ‘what about Portugal?’ has likewise been posed by those seeking to decentre Britain’s own history of participation in the slave trade.

These two books from historians immersed in the lusophone colonial world bookend the beginning and end of Portuguese involvements in the Atlantic slave trade. In The Heretic of Cacheu Toby Green explores the minutiae of everyday interactions among Portuguese slave traders, mixed-heritage middle-women, and African chiefdoms in a town where trans-Atlantic slave-trading was taking off in the early 17th century. In Worlds of Unfreedom, Roquinaldo Ferreira develops a similarly fine-grained account of Portuguese traffickers’ relationships with Africans at a time when abolitionism was threatening the economic dominance of all those complicit in that trade.

Green’s story is centred on the arrest and Inquisitorial trial for heresy of Crispina Peres, a woman of Portuguese and Bainuk descent, who was married to the former captain-general of Cacheu in today’s Guinea-Bissau, in the mid-1600s. Like most of the town’s elite, Peres both owned domestic slaves and traded captives to the Portuguese ‘market’. The latter were obtained primarily by armed groups known as gampisas in the interior, and by Bijagó islanders who lived on the offshore archipelago and raided mainland communities. Local and more distant African polities – the Bainuk, Pepel, Flouk, Mandinga, Jolof, and Serèer – variously avoided, resisted, or profited from the Atlantic trade networks.

One of Green’s key insights is how tenuous the boundary was between the different forms of slavery in Cacheu. Societies in West Africa had long practised a domestic form of enslavement for war captives and those born into slavery. These captives survived within the owner’s household in relationships of dependency, subject always to their caprice. But the slavery introduced by the Portuguese was different. It entailed the reduction of captives to the status of commodity for export. Green writes that Peres had ‘a clear understanding of the hatred that underlay her daily interactions’ with the enslaved in her household, but exploited their ‘terrible fear of being sold into Atlantic trafficking’. Household slavery in Cacheu was at least preferable to the Middle Passage. The town’s social hierarchy rested on free people’s attempts to mark their free status and enslaved peoples’ efforts to demonstrate their value to local owners and avoid being sold to the traffickers.

Green describes life in Cacheu in far more detail than historians of local colonial societies usually manage thanks largely to the Inquisition records of witnesses’ interrogation for Peres’ trial in Lisbon in 1665. They included some of Peres’ own household slaves. One of them, Sabastião Rodrigues Barraza, claimed that he had denounced Peres because he had been promised his freedom by her accusers. These included two of Peres’ major commercial rivals and the main instigator, the disgraced priest Luis Rodrigues, who had himself been arrested by the Inquisition for soliciting women in the confession booth. Together these men conspired to denounce Peres for the ‘use of African healing and knowledge’ which, they knew, would be interpreted in Lisbon as an assault on empire. Her real crime, Green argues, was her challenge to these Portuguese men’s dominance of the local slave trading economy. Having spent three years in the Inquisitorial jail, Peres died soon after her return to Cacheu in 1668.

Ferreira’s account takes place two centuries later and more than 2,000 miles south in Angola, the main source of captives for the by-then illicit slave trade. As the Portuguese historian João Pedro Marques has suggested, the imperial authorities adopted a gradualist approach after British abolition in 1807, partly as a ‘cautious guarantee’ to Portugal’s domestic antislavery campaigners, and partly to assuage pressure from abroad. The loss of Brazil as the main source of demand for Portuguese trafficking after 1822 meant that the empire had less to lose from enforcing abolition and more to gain by taking some of the initiative back from Britain. Enforcing abolition of the Atlantic trade also enabled Portugal to retain captive labour within its African colonies.

Like the British and French, the Portuguese were intent by the mid-19th century on extracting Africa’s raw materials. They learned from the British how to use antislavery initiatives to pursue this new post-slavery project, invading the Kongo kingdom and taking control of the Bembe copper mines in 1856 on the pretext of suppressing slavery before the British could do so. Their ‘antislavery’ military expedition conveniently carried mining equipment. Abolition thus became ‘a tool for the creation of new forms of unfreedom’. As one French official explained, referring to the British practice of forcing Africans ‘liberated’ from slave ships to work elsewhere in its empire, ‘England herself gives us an example’, the only difference being that the ‘French bought their captives on land and the English seized theirs at sea and forced them to emigrate’. The Portuguese justified the removal of African men and women from Angola to work on the coffee plantations of São Tomé and Príncipe by invoking the British example of forcing ‘apprentices’ from Sierra Leone to work on Caribbean sugar plantations.

Both authors take great care to emphasise the agency of African people. Ferreira tells the intriguing story of Eufrazina, an enslaved African woman whom the Luanda businesswoman and slave trader Dona Ana Joaquina sent as envoy to negotiate a treaty with the powerful Lunda Kingdom. Anticipating the supply of captives for the Atlantic trade drying up, Joaquina hoped to initiate and monopolise a new trade in wax, ivory, and captives purely for the local market. British officials praised her for leading ‘the only attempt to give capital a more wholesome direction’ by developing sugar production using locally enslaved African labour. But both books are obliged, ultimately, to recognise the limited ability of their African protagonists to challenge a highly militarised and increasingly rich and powerful Europe. At both the beginning and the end of slavery, West Africa’s economies were reoriented around European demands, first for the extraction of captives, and then for the exploitation of land and labour in situ.

In the meantime, between the 1650s and the 1850s, mixed-race elites had more power in the Portuguese slave-trading entrepôts than one might expect. In 1836, Benguela’s Portuguese governor lamented that: ‘Every time that elections have taken place ... those elected have always been either blacks or mixed-race individuals [pardos], and whites have been excluded.’ The resistance that Portugal encountered from these groups as it abolished its slave trade and developed as a territorial colonial power is a key part of the region’s history, as Ferreira’s book shows. Together these painstakingly researched studies recreate a world in which slavery was a significant but widely disavowed part of everyday life.

-

The Heretic of Cacheu: Struggles Over Life in a Seventeenth-Century West African Port

Toby Green

Allen Lane, 368pp, £25

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link) -

Worlds of Unfreedom: West Central Africa in the Era of Global Abolition

Roquinaldo Ferreira

Princeton University Press, 304pp, £30

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Alan Lester is Professor of Historical Geography at the University of Sussex.