‘The Maginot Line’ by Kevin Passmore review

The Maginot Line: A New History by Kevin Passmore confronts the myths surrounding the fall of France in 1940.

Visitors to the Maginot Line fort at Schoenenbourg can experience something of the cold, dark, and damp conditions endured by the French forces who spent months living 30 metres underground during the Second World War. At the fort’s entrance, plaques honour the bravery of the combatants who were ‘handed over’ to the enemy on 1 July 1940 ‘without having been defeated’. The defiant tone of the memorials is in marked contrast with the criticisms that have often been levelled at the Maginot Line, and which lie at the heart of Kevin Passmore’s book.

The fall of France in 1940 remains shrouded in myth and controversy. Claims that the French lacked the will to fight, that soldiers sat idly behind outdated fortifications, and that the nation’s leaders were fundamentally defeatist continue to pervade popular perceptions. Passmore sets out to dismantle these myths. He disputes notions that the fortifications’ flaws reflected any cohesive national ‘mentality’, arguing instead that the problems were a result of political and military disagreements concerning pacifism or militarism during the period in which the defences were conceived and constructed. To make his case, Passmore adopts a more expansive approach than is suggested by the book’s title: the Maginot Line becomes a concrete lens through which to explore the history of France from the late 1920s to 1940.

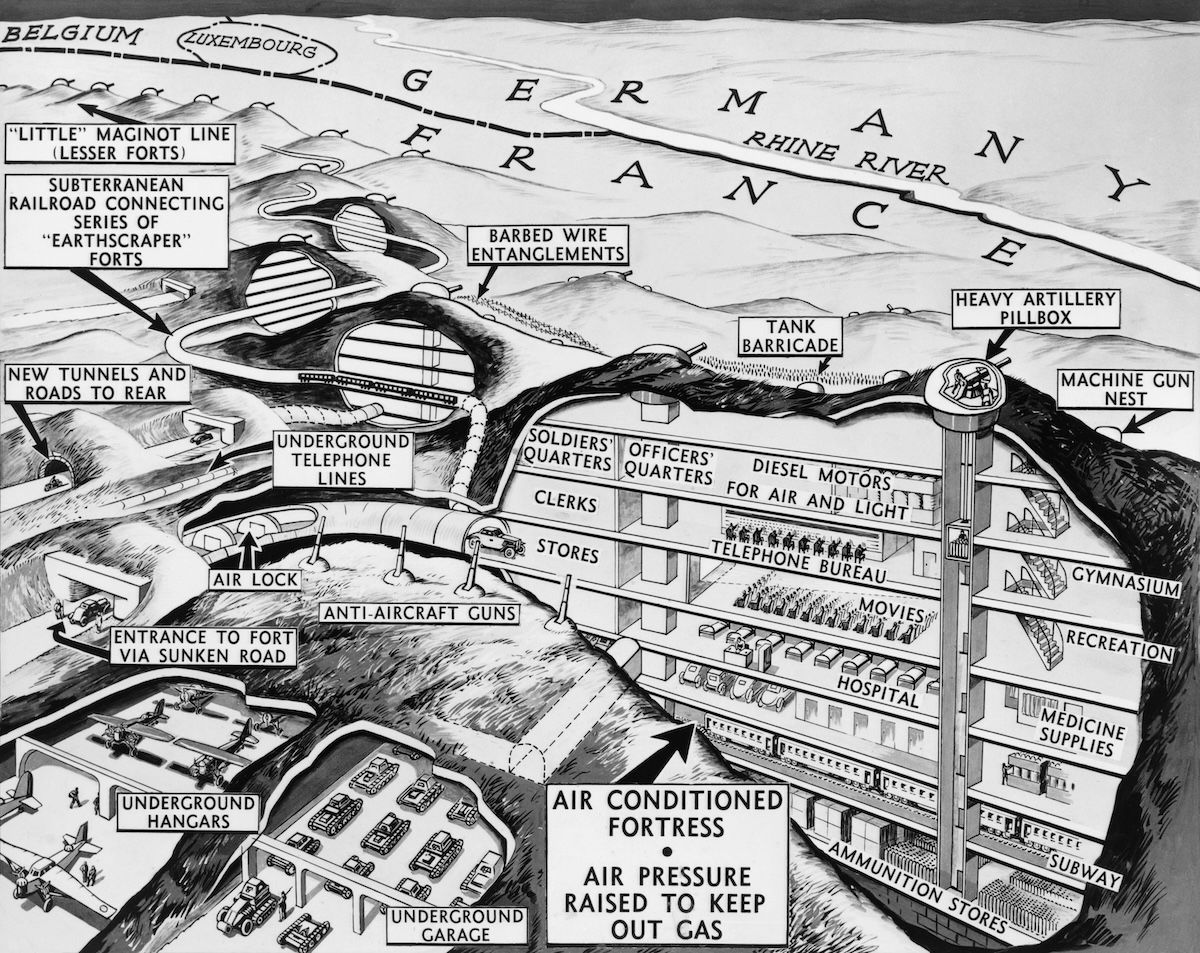

It was not until five years after the death of André Maginot in 1932 that the forts and bunkers built along France’s eastern border became widely known by his name. Appointed as war minister in November 1929, Maginot argued that the defences would be essential for a safe reconciliation with Germany. Until 1929 French generals had considered a defensive war unlikely because Germany had been so weakened by the Treaty of Versailles. Nevertheless, while pacifism was widespread, most French people followed Maginot in wanting to ensure France’s ability to defend itself. It was not without some irony that the forts intended to protect national boundaries were built and staffed in significant part by immigrant workers, including from Germany and Italy, whose loyalties were often questioned by the French authorities. There were numerous cases of suspected espionage, although often they turned out to be unfounded. Big business competed for contracts and played a key role in the forts’ construction, which cost around six billion francs (roughly seven billion euros in today’s money). The designs were produced by a new generation of engineers educated at the École Polytechnique and reflected the modernist architectural styles of the time. The accommodation was compared to ‘upside-down versions’ of Le Corbusier’s skyscrapers and included central heating, air conditioning, and electric ovens long before they were common features of domestic homes. However, the sleeping areas provided little modern comfort. Damp was a significant problem, while air quality was poor.

As international tensions rose in the late 1930s, the issue of fortification became increasingly polarised. Those in favour of appeasement saw fortifications as a defence; others, especially on the left, were keen to directly confront fascism. After Belgium declared neutrality in 1936, a contrast emerged between the French government’s public support for a continuous barrier along France’s borders and the resources it allocated, as prime minister Édouard Daladier began to realise the significant financial cost involved. The government sometimes gave misleading messages about the inviolable nature of the fortifications to an anxious public. Propaganda films sought to reassure the people that the Maginot Line would protect France’s borders, while also emphasising that the fortifications were just one element in the defence plans.

At the outbreak of war in September 1939 the Maginot Line fulfilled its function of covering French mobilisation. However, the soldiers, who were not properly kitted out, endured the coldest winter since 1838. Many suffered from fatigue as a result of spending extended periods underground, though Passmore refutes suggestions that morale was poor during the Phoney War, and argues that it had improved significantly by the time the fighting began in May 1940. Far from seeing French military doctrine as the product of sclerotic thinking, Passmore points to commander-in-chief General Maurice Gamelin’s orders to advance into the Low Countries under the Dyle-Breda plan to emphasise how the French army did not merely seek refuge in defensive strategies.

The German army’s original intention of invasion through Belgium, sweeping northwards to the coast, would not have been so immediately disastrous for French forces. However, on 12-13 May 1940, German forces concentrated armoured and air forces on the weakest points in the French defences at Dinant and Sedan. Weaknesses in the depth of the northern fortifications meant that if one line fell, the others would be vulnerable to rear attacks. On 14 June 1940 six German divisions attacked the line from Saint-Avold to Puttelange with intense artillery bombardment followed by an infantry assault, compelling French forces to retreat. Ultimately, however, it was Allied weakness in the air, the inability to locate German forces, and communication problems that proved fatal to the French.

Overall, the Maginot Line’s contribution to the defence of France was mixed, Passmore argues. It blocked the easiest routes to Paris, Alsace, and Nice and was not the disproportionate burden on spending that it is often thought of as being. It was less susceptible to technological obsolescence than other forms of weaponry, though its construction coincided with a revived emphasis on mobility in battle. But most importantly, the book refutes the portrayal of the Maginot Line as a symbol of a defeatist French mentality that, having been originally propagated by supporters of Charles de Gaulle, has been echoed in numerous studies since 1945.

-

The Maginot Line: A New History

Kevin Passmore

Yale University Press, 512pp, £30

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Karine Varley is Senior Lecturer in French and History at the University of Strathclyde.