How Medieval Scribes Balanced the Books

As the medieval book trade declined, Oxford scribes had to turn their hands to other crafts to get by.

At its height Oxford’s book trade enjoyed the establishment of Dominican and Franciscan friaries in need of books for university activities and preaching, and an early demand from lay figures for luxury private prayerbooks. From the 13th century, these books were increasingly produced not by monks in monastic scriptoria but by professional craftspeople.

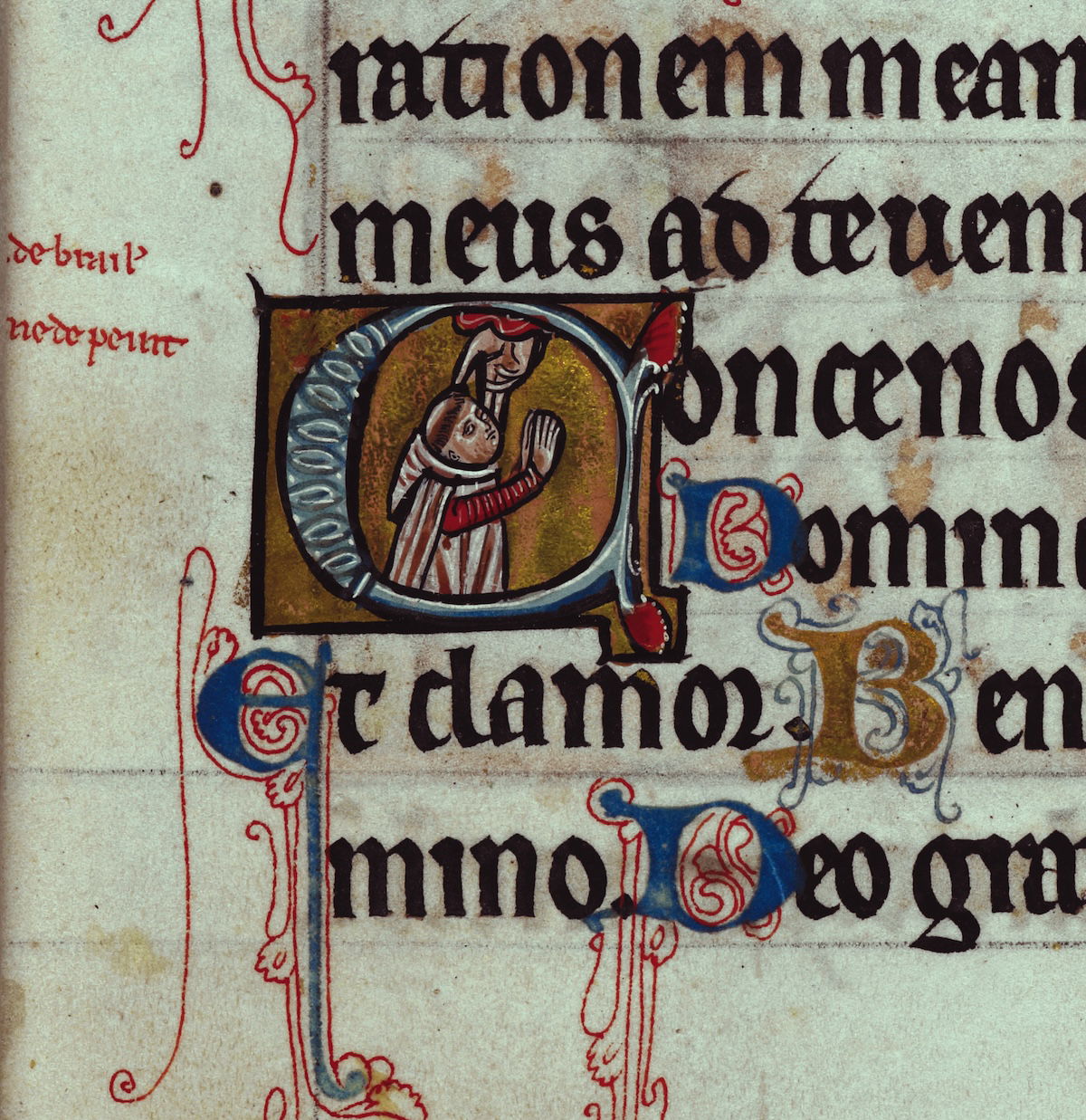

The best documented scribe of medieval Oxford is William de Brailes, who, in the mid-13th century lived in Catte Street, the city’s book trade quarter. He was an exceptional scribe and artist, producing several illuminated works for religious houses and wealthy lay owners, including the so-called De Brailes Hours (c.1240), the earliest known stand-alone Book of Hours written in England. At a time when most scribes remained anonymous, de Brailes signed his work and added a self-portrait, captioned: ‘W. de Brailes who painted me’. He is further recorded in several property deeds as a witness and as a property owner himself, reflecting his financial success.