‘The Diver of Paestum’ by Tonio Hölscher review

The Diver of Paestum: Youth, Eros and the Sea in Ancient Greece by Tonio Hölscher – and translated by Robert Savage – searches beneath the surface for the meaning behind a beguiling fresco.

On 3 June 1968, as protesting students occupied the Sorbonne, and Robert Kennedy was preparing his speech to celebrate victory in the California presidential primary, a small team of archaeologists, led by Mario Napoli, were uncovering a remarkable tomb at Paestum. The tomb consisted of five frescoed slabs of travertine limestone, four walls and a ceiling – its dimensions in situ roughly 200 × 100 × 80 centimetres – dating to c.480 BC. Such elaborate tombs were common at Paestum and elsewhere in Magna Graecia, which encompassed the southern part of the Italian peninsula and Sicily. Paestum (or Poseidonia, to give the ancient city state its Greek name) had been founded in about 600 BC, south of Neapolis (Naples), overlooking the Gulf of Salerno, amid fertile plains that today are home to Mediterranean buffalo whose milk is used to produce mozzarella di bufala.

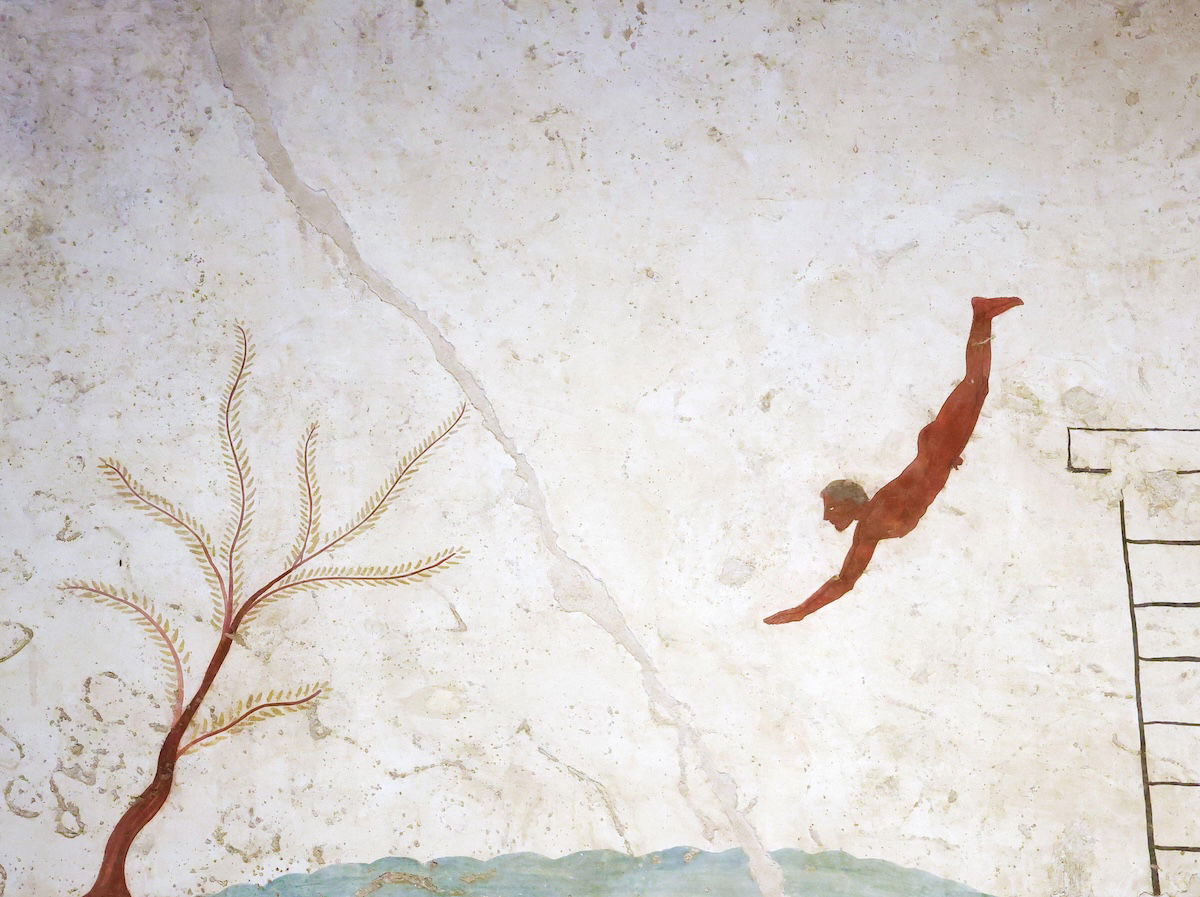

The long side panels of the Paestum tomb show a symposium, with older and younger male figures reclining on dining couches (klinai), variously in rapt debate or post-prandial merriment, such as playing an aulos (a twin-piped flute), or holding a lyre, while others are shown participating in kottabos, a game invented in Greek Sicily that involved flicking the last dregs of wine from a shallow drinking dish (kylix) at a target. (Plato noted his disapproval of the game when visiting Syracuse.) The end panels show other figures dancing or playing instruments, and a young man next to a table on which is a large vessel (krater), presumably serving the watered-down wine that is being abundantly consumed. However, it is the ceiling panel that gives the tomb its name. It depicts a young man, probably an adolescent of military training age (ephebos), identifiable by his lithe body and scarce facial hair, captured mid air, diving head first into a body of gently rippling water, having jumped from a tower to his right. The only other details in the otherwise minimalist composition are a couple of stylised trees and a painted black line framing the panel, with a delicate palmette in each corner.

Starting with Mario Napoli, most interpretations of the image of the diver have been eschatological, seeing it as a representation of the dead youth leaving the world of the living and plunging towards the unknown afterlife, an ‘image of the passage of the soul through the purification of water’. However, other scholars have conducted erudite exchanges in academic journals, such as William J. Slater, who in 1976 suggested that the diver was ‘a petauristarius’, an aerial acrobat, who often entertained at symposia. In 1977 R. Ross Holloway instead suggested that such theories overlooked the exotic elements of the paintings, the drinking and overtures of homosexual love, that brought to mind a fragment of a poem by the Greek lyric poet Anacreon (c.573-495 BC): ‘Burning and drunk with love, I dive into the grey sea from the white rock.’

In his new study (admirably translated by Robert Savage), Tonio Hölscher, Professor of Classical Archaeology at the University of Heidelberg, uses his rhetorical skills to patiently and persuasively build his own argument, in an eloquent dialectic with previous scholars. Hölscher reminds us that the life stages for elites in Greek society were very structured, with several age-specific roles before entering life as a young citizen (néos) and later married life, perhaps holding public office, as an adult (anér). As a child (pais), our diver would have lived in the sheltered environment of the family home, and the social order of the city (polis), but as an adolescent (éphēbos or ephebe), he would have spent his time with his peers, in gymnasia and in military training, often well beyond the limits of the city in the wilderness of the countryside (eschatiá). There he would have learned to hunt animals, armed only with a spear (dory) or a sword (xiphos), or gone swimming in the sea, where there was ample opportunity for diving from cliffs, or perhaps from one of the defensive look-out towers built along the coast, or even from an elevated hunting scaffold, erected for sighting shoals of tuna, a culinary favourite of a people for whom mastery of the seas was an important part of their identity. Hölscher shows us examples of painted Greek pottery depicting similar scenes of youthful enjoyment, and suggests that Paestum’s diving youth captures the ‘suspended instant of descent … pure surrender to the senses’.

Later, the young man would have been admitted to symposia, becoming part of the networks in the upper echelons of society, where he and his peers would ‘master the art of conversation, dazzle with their wit’, each under the watchful eye of an older escort. Co-existing alongside heterosexual attitudes to marriage and family life, these mentors in homoerotic liaisons were an integral part of elite Greek culture that scholars through the ages have often highlighted, but which Hölscher reminds us must not be used as a cover for modern paedophilic practices within academic or religious institutions. Hölscher also argues that while ancient Greek society was heavily patriarchal, the grim picture of a woman’s role as solely domestic, as also suggested by scholars of previous generations, was inaccurate. Girls (kórai) would go through similar life stages to their male counterparts. A young woman preparing for married life (nýmphe) would also venture beyond the family home with her peers, to swim in grottoes beside the sea, collect water from fountain houses, and visit sanctuaries. Yet examples of Greek art depicting young women undertaking such activities were previously dismissed as representations of myths by scholars whose own gilded life experience may not have ventured much beyond their own college quads.

In conclusion, Hölscher suggests that the images of the symposium and the diver in the Paestum tomb provide a powerful evocation of exuberant youth, capturing the zeitgeist of the lifeworld of the entombed adolescent, provided by those who survived him. The fresco is a welcome glimpse of the zest for life that existed in the ancient Greek world.

-

The Diver of Paestum: Youth, Eros and the Sea in Ancient Greece

Tonio Hölscher, translated by Robert Savage

Polity, 136pp, £20

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Philippa Joseph is a member of the History Today editorial advisory board.