‘The First King of England’ by David Woodman review

The First King of England: Æthelstan and the Birth of a Kingdom by David Woodman looks beyond the empty tomb to find perhaps the most consequential monarch of the Anglo-Saxon age.

Tucked into a corner of the north aisle of Malmesbury Abbey is the tomb of the Anglo-Saxon king Æthelstan. Installed some five centuries after the king’s death, the tomb is a fine, if unremarkable, example of 14th-century funerary sculpture featuring a generic royal effigy atop an unadorned chest. Yet all is not as it seems. The tomb is – and perhaps always has been – empty. It was designed as an object of veneration, a way of creating an image of the king and calling it memory, in the hope of establishing a new royal cult. Æthelstan himself is nowhere to be found.

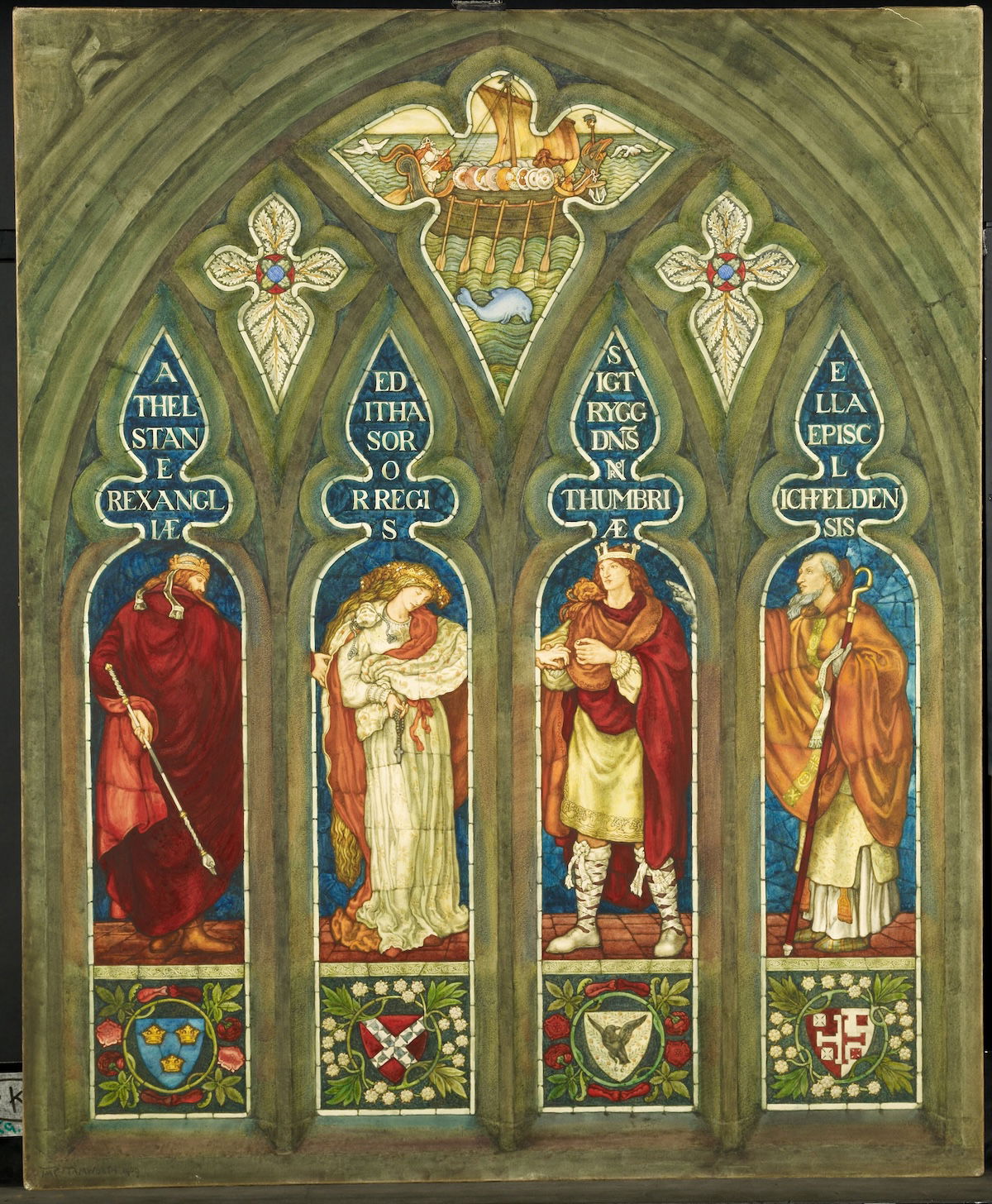

The paradoxical quality of Æthelstan’s tomb captures the challenges confronting his would-be biographers. His significance as a historical figure is undeniable: his conquest of Northumbria and the submission of the kings of Wales, Scotland, and Strathclyde made him both the first king of a unified England, and, in his own words, ‘king of the whole of Britain’; his victory at the Battle of Brunanburh in 937 was among the most significant English military successes of the pre-Conquest period; and his patronage of the Church laid the foundation for the ecclesiastical reform movement of the mid-tenth century. Nonetheless, as David Woodman writes in his splendid new biography, ‘working from the patchy, jaundiced, and stereotypical nature of the surviving sources, it is notoriously difficult to know anything about Æthelstan the man’. We know Æthelstan as a reputation, but not as a person. No contemporary life of Æthelstan survives and we have only scattered details regarding his childhood, the conditions under which he acceded to the throne, his manner of rule, and the circumstances of his death and burial. The few scraps we do know of his life derive primarily from the works of William of Malmesbury, writing nearly 200 years later. Even such basic matters as the chronology of his reign remain subject to controversy. A conventional narrative biography would be impossible.

These difficulties make Woodman’s achievement all the more impressive. By hewing rigorously to his sources and carefully weighing his evidence, Woodman takes his readers as close as possible to a ruler who was arguably even more important than his grandfather, Alfred, to the formation of the English state. Woodman wisely eschews a traditional chronological account in favour of a series of thematic chapters on such topics as Æthelstan’s establishment of an English kingdom, his development of a centralised royal bureaucracy, his relations with the Church, and his European reputation, among others. Readers encountering Æthelstan for the first time will be grateful for Woodman’s lucid and compelling prose as well as his authoritative presentation of what would be, in a lesser scholar’s hands, a bewildering mess of charters, annals, laws, and ecclesiastical records. More expert readers will appreciate his judicious weighing of the evidence for Æthelstan’s reign as well as his insightful discussion of problems such as the identity of the anonymous court scribe ‘Æthelstan A’ and the question of the king’s unnamed half-sister, an enigmatic figure referred to only obliquely in the records of his reign.

The basic facts of Æthelstan’s life are these: according to the 12th-century William of Malmesbury, Æthelstan acceded to the throne of Wessex in 924 at the age of 30, suggesting he may have been born c.894. However, as the source of William’s information is unknown, it is impossible to judge its reliability. Æthelstan was the son of future king Edward the Elder (himself the son of Alfred the Great) and his first wife Ecgwynn, whose background is unknown. Various sources suggest that she was of humble birth and perhaps Edward’s concubine rather than his wife, though these stories may simply have been the inventions of Æthelstan’s political rivals. He spent at least part of his childhood at the court of his aunt, Æthelflæd, ‘Lady of the Mercians’, and her husband Æthelred. On Edward’s death, Æthelstan moved swiftly to secure his position as king and thwart the ambitions of his younger half-brothers, sons of Edward’s second wife Ælflæd. Both brothers would later die under suspicious circumstances, though in the absence of reliable sources, what looks sinister to modern eyes may just have been common matters of illness and bad luck.

Over the first three years of his reign, Æthelstan consolidated his rule over the formerly independent kingdoms of Wessex, Mercia, and East Anglia, though the regions north of the Humber remained just beyond his grasp. In 926 Æthelstan arranged the marriage of an unnamed and otherwise unattested sister to Sihtric, king of Northumbria, who died just a year later. Æthelstan quickly led his army north to displace Sihtric’s successor Guthfrith, thereby bringing the north under his control. On 12 July 927 the rulers of Britain’s remaining kingdoms recognised his overlordship, effectively making him the first king of a united England. In the years following, he consolidated his authority through the issuance of legislation on such issues as the maintenance of public order and the care of the poor, the distribution of land, and a vigorous campaign against theft and other forms of lawbreaking. In 937 he defeated a combined Irish-Scandinavian army at Brunanburh, the precise location of which is unknown. The scale of the battle and Æthelstan’s overwhelming victory secured his reputation as a military leader, though the actual significance of the engagement remains a matter of dispute. Æthelstan died two years later of unknown causes and was – again, for reasons that can only be guessed at – buried at Malmesbury.

Woodman’s accomplishment lies in his ability to situate these crumbs within a broader context to produce a persuasive account of the ruler with the greatest claim to be the first true king of England. His biography not only documents a crucial moment in English political history, but it also illustrates the complexity of early medieval state-formation. This volume is no mere empty tomb, but a vital portrait of tenth-century kingship in action.

-

The First King of England: Æthelstan and the Birth of a Kingdom

David Woodman

Princeton University Press, 344pp, £30

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Andrew Rabin is Professor of English at the University of Louisville.