Wimpy vs McDonald’s: The Battle of the Burgers

In the 1970s and 1980s Wimpy faced off with McDonald’s in a battle over what it meant to eat British.

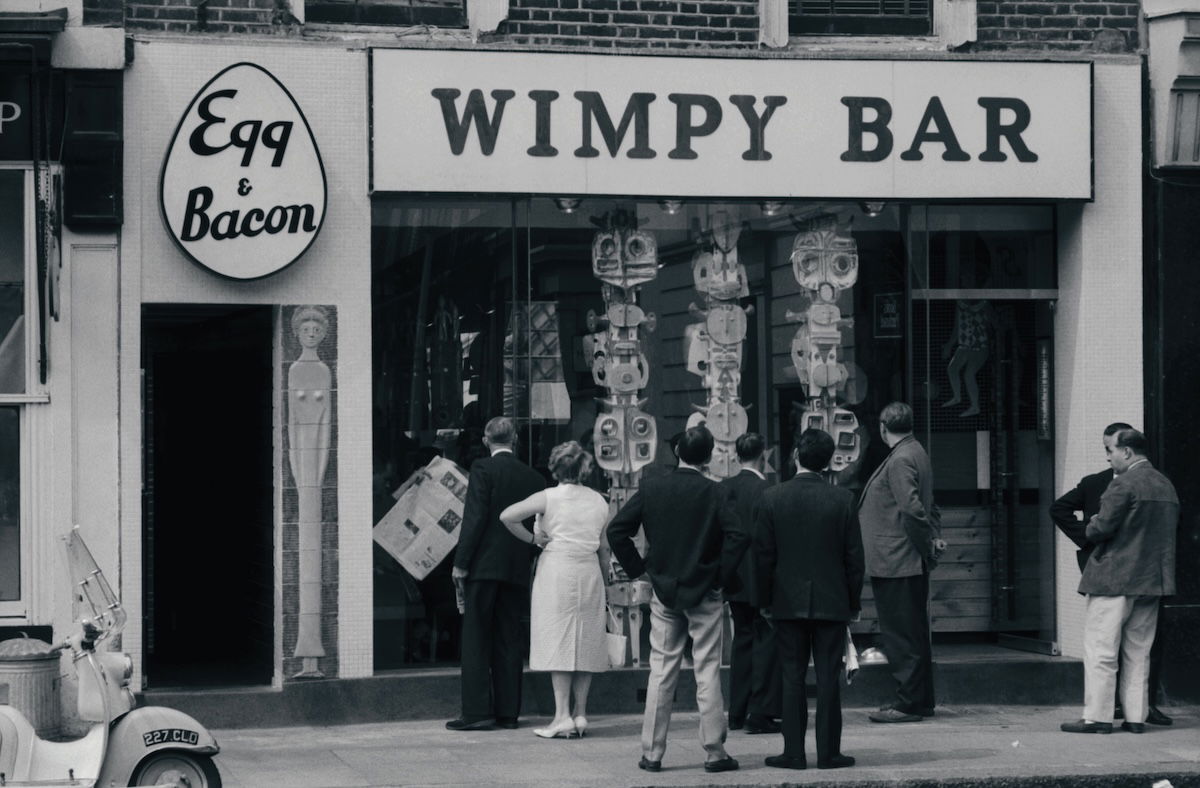

When the burger landed on the tables of the first Wimpy Bar in 1954, it marked a new era of modernity, global connection, and convenience for a Britain rebuilding from the austerity of the Second World War. But it later found itself at the heart of a cultural war against these same ideals. ‘The McDonalds are coming’, declared the Reading Post in March 1983 as Wimpy’s competitor gained ground on the British high street. ‘It looks like the battle of the burgers is about to erupt.’