‘The Colonialist’ by William Kelleher Storey review

Though his relics are reviled, his impact is more keenly felt than ever. Can The Colonialist: The Vision of Cecil Rhodes by William Kelleher Storey find the man for our time?

He was a polarising figure, revered by his admirers as a patriotic hero yet reviled by others for his egotism and amorality. At least one journalist thought he had a ‘vein of vulgarity’, exemplified by ‘a passion for diamonds and a contempt for women’. This powerful man was susceptible to ‘flattery of the grosser kind’ and showed ‘a tendency to bully those who were in no position to retaliate’. He was guilty, too, of ‘racial arrogance’. His peculiar brand of charisma worked by converting conspicuously bad behaviour into a display of dominance. ‘We have always a weakness’, Edward Roffe Thompson wrote, ‘for the strong man who shows his strength by smashing the Ten Commandments’.

Cecil Rhodes as the Donald Trump of the late 19th century: the analogy is less outlandish than it might seem. Representing a disruptive combination of wealth, celebrity, and megalomania, Rhodes mixed business with politics and conflated territorial conquest with personal aggrandisement. The Trump that returned to power for a second term has been increasingly Rhodes-like in his fixation on enlarging the boundaries of the United States, and in his view of land inhabited by other people as inert repositories of extractable resources. Like Rhodes, oddly, Trump reveres the British monarchy while disdaining almost every other institution. Despite its hostility to immigration, the Trump administration has rolled out the red carpet for the population most beloved by Rhodes, the white minority of South Africa. The Trumpist magnates who grew up in South Africa, Elon Musk and Peter Thiel, are even more indebted to Rhodes’ technologically sophisticated, surveillance-intensive, and militarised brand of capitalism. Of course, there are significant differences, too; Rhodes saw the accumulation of wealth as a means to the ultimate goal of imperial expansion rather than the other way around. Still, one of the frustrations of William Kelleher Storey’s thorough but unfocused biography is that it holds back from acknowledging the troubling connections between Rhodes’ world and our own, even when they leap off the page.

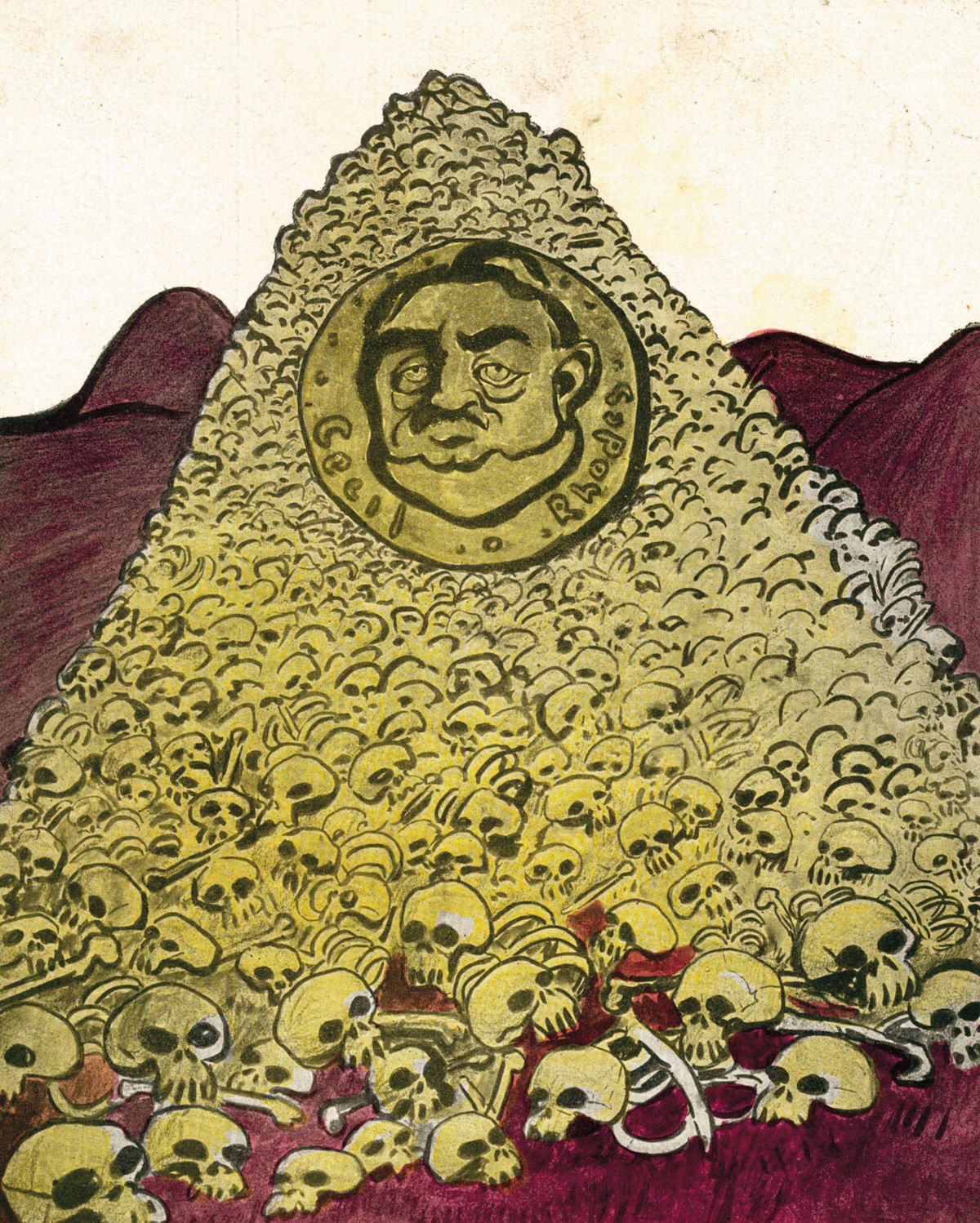

What does it mean to write the life story of an imperial conqueror in 2025? The challenge is especially acute with Rhodes, who styled himself a heroic figure of historical destiny and persuaded many others to see him that way. His acolytes fostered a posthumous cult of the Great Man, embodied in bombastic memorials across South Africa and beyond. Famously, the Rhodes Must Fall protest movement began in 2015 with the aim of toppling one of his statues, at the University of Cape Town. Installed in 1934, Rhodes’ likeness sits on a plinth inscribed with some lines from Kipling, evoking the fantasy of continuous British control from the Cape to Cairo: ‘I dream my dream by rock and heath and pine / Of Empire to the northward.’ The colony named in Rhodes’ honour, today independent Zimbabwe, endured until 1980 as one of the world’s last bastions of racial minoritarian rule. The diamond and gold mining operations that made his fortune pioneered systems of segregation, confinement, and compulsion that were foundational to apartheid in South Africa. Rhodes’ claim to greatness has always been entangled with armed expansionism and white supremacy.

Faced with such a problematic subject, Storey is conspicuously reticent about the role of the biographer. Aside from a few perfunctory pages at the outset about Rhodes Must Fall, we get little sense of how contemporary debates shaped the book and whether it is intended as a response to the British history wars incited by the Rhodes statue at Oriel College, Oxford. It is true, and rather striking, that nearly four decades have passed since the last major Rhodes biography, Robert Rotberg’s The Founder (1988), which remains indispensable even if its heated Freudian speculations have fallen out of fashion. It is also true, as Storey points out, that the Africans who worked for Rhodes, or had their land stolen by him, have left scant documentary traces for historians to examine. Given the vexed imperial tradition of hero worship, however, Storey might have mounted a more energetic case for revisiting the cradle-to-grave narrative of one endlessly memorialised man. The oddly generic title of the book, along with a subtitle that could be read as subtly glorifying, tell the reader not to expect a slashing polemic but offer no clear sense of the author’s perspective beyond that.

The closest Storey comes to offering a position on Rhodes Must Fall is the penultimate sentence of the book: ‘It will be much easier to remove a few statues than to reverse the legacy of Cecil Rhodes.’ Either a bracing materialist reproach to symbolic politics or a condescending dismissal of hard-fought activism, depending on your point of view, this statement is typical of the book as a whole: the debunking of the Rhodes myth is so bound up with awe of his achievements that it could almost be mistaken for an affirmation instead. The reason that Rhodes’ legacy will be so difficult to unwind, as The Colonialist shows in painstaking detail, is that his empire-building aspirations translated into durable structures woven through everyday life. That is why Storey likens Rhodes to industrial innovators including Samuel Morse, Thomas Edison, and Henry Ford; their respective achievements (the telegraph network, the power grid, the assembly line) reshaped social orders around new technologies. Presumably aware that this could be seen as a flattering comparison, Storey complicates it by labelling Rhodes’ mining-and-settlement empire a ‘disassembly line’, underscoring that he amassed power through racial discrimination, physical violence, and environmental destruction.

Little of this will come as a surprise to historians. But Storey performs a service by documenting just how consistently and completely Rhodes’ rise disadvantaged the black Africans of his adopted country. Acting as the determined gravedigger of the so-called ‘Cape liberal’ tradition, Rhodes spent his political career favouring legislation that replaced legal equality with racial despotism: outlawing gun ownership by Africans, allowing the police to detain them without trial, and hollowing out their right to vote with property qualifications and literacy tests. In his capacity as mine owner, Rhodes pursued a parallel agenda of subordination, enshrining a rigid hierarchy of white supervisors and black labourers. This exposed African miners to immensely disproportionate danger in tunnels that drove ever deeper into the earth; among the thousands who died on the job, more than 160 perished in a single 1888 fire, caused in part by shoddy design, for which Rhodes and his company escaped any accountability. Rhodes also presided over the concentration of black miners in prison-like ‘compounds’, justifying the most invasive bodily searches imaginable on the grounds that tiny gems could otherwise be smuggled out. Among the few goals that Rhodes did not succeed in realising was the codification of a legal right for white employers to beat African workers.

Beyond showing that Rhodes’ achievements were as morally dubious as they were socially significant, The Colonialist quietly undermines the Great Man idea by showing just how much of his success Rhodes owed to luck. His arrival in South Africa in 1868, facilitated by family connections and a free government grant of 200 acres, happened to coincide with the discovery of diamonds. As Rhodes’ annexationist ambitions grew, he could take advantage of a friendly atmosphere for the incorporation of chartered companies, an old imperialist vehicle that made a comeback in the late 19th century as politicians grew skittish about conquest by government action. The peculiar institution that was the British South Africa Company – combining virtually unlimited operational authority for Rhodes, a military force armed with machine guns, the power to impose taxes on Africans, and a mandate to return profits to investors back in Britain – could hardly have suited his needs better. Yet Rhodes’ instincts were not always sound. Shares in the company slumped when the promise of an El Dorado in what is now Zimbabwe failed to materialise. What is more, Rhodes’ costly drive to the north was a kind of overcompensation for an earlier miscalculation: failing to grasp the extent of gold deposits on the Witwatersrand and missing out on an even bigger fortune as a result.

Biography is not well suited to questioning the significance of the individual. But some of the most interesting passages of The Colonialist demonstrate that Rhodes’ project was a collective effort. His devotion to seizing land for the benefit of the Anglo-Saxon race emerged from the febrile atmosphere of late Victorian Oxford, where John Ruskin told undergraduates that England must ‘reign or die’. Obsessed with infrastructural networks as the path to progress, Rhodes managed to impose his vision on the landscape only with the help of a small army of mining, telegraph, and railway engineers. His bloody incursion into Zimbabwe was underwritten by a long list of aristocratic and otherwise influential shareholders in the British South Africa Company, who lent their prestige to a legally dubious land grab. Cheerleaders in the press, meanwhile, burnished Rhodes’ reputation as a continent-bestriding colossus. Storey might have spent less time on the technical details of mining machinery and more on the ways that violence inflicted on southern Africa emerged from ideological networks and material interests with deep roots in British society. Perhaps the next book written about Rhodes will abandon biographical narrative altogether, shifting focus to the people, institutions, and ideas that made his life’s work possible. That is a story with undoubted relevance to our political moment.

-

The Colonialist: The Vision of Cecil Rhodes

William Kelleher Storey

Oxford University Press, 528pp, £30.99

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Erik Linstrum is Professor of History at the University of Virginia and author of Age of Emergency: Living With Violence at the End of the British Empire (Oxford University Press, 2023).