‘Hitler’s Deserters’ by Douglas Carl Peifer review

Hitler’s Deserters: Breaking Ranks with the Wehrmacht by Douglas Carl Peifer surfaces the stories of those who sought to sit out the Second World War.

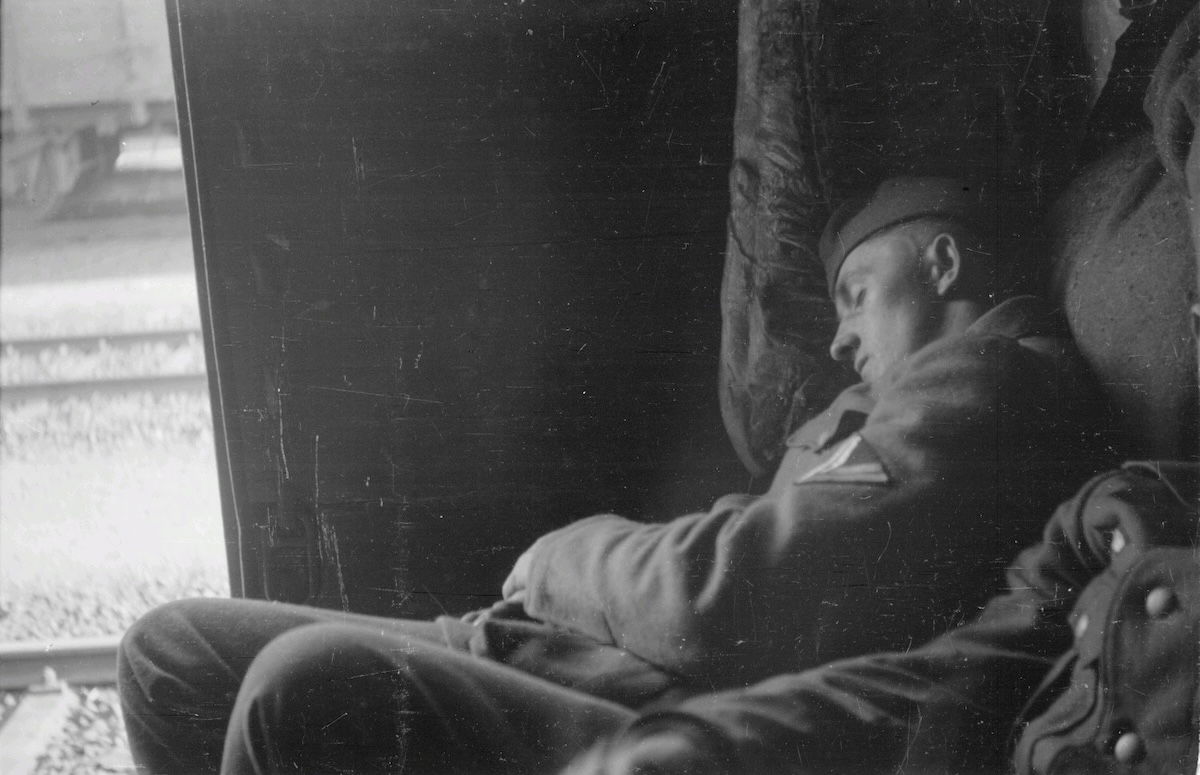

In 1989, as the Berlin Wall was about to fall, Turkish sculptor Mehmet Aksoy was completing his ‘Memorial for the Unknown Deserter’. Originally designed for Freedom Square in the West German capital Bonn it was placed, instead, at Unity Square in Potsdam, formerly in East Germany, in 2001. The sculpture, carved from Carrara marble, depicts an absence: in the centre of a large, rock-like formation is a human-figure-shaped hole outlining the space where a soldier might have stood. Douglas Carl Peifer’s work, Hitler’s Deserters, tells the story of men who similarly absented themselves from active duty in the German Wehrmacht during the Second World War. Since the precise number of those who committed this ‘crime’ cannot be known, Peifer’s focus is on those who were prosecuted for it. Military courts and tribunals sentenced an estimated 18-20,000 German soldiers, sailors, and airmen to death for desertion, ‘subversion of the military spirit’, and treason. Peifer recounts their possible motivations for evading military service and the paths taken to do so. It is a well-told tale, one that manages to humanise the victims of Nazi military justice and embed their individual narratives in a thorough examination of the world at war.

Peifer’s foremost contribution to the study of desertion in the Third Reich is bringing existing scholarship written in German to an English-speaking audience. This is the first comprehensive, academically rigorous English language account by a professional historian (a book with the same title was published in 2013 by a former conscript in the Swedish Air Force, but it was a popular history lacking references). Peifer has also carried out his own extensive research in the archives, making notable use of the Swiss Federal Archives in Bern, since neutral Switzerland was a key destination for many fleeing the Nazi war machine.

The book is well structured and accessible for the non-Wehrmacht-specialist, and readers not well versed in exactly what constituted Nazi-era military ‘justice’. Peifer outlines the military penal code and special wartime criminal laws that dictated how deserters were to be treated; the ideological obsession – shared between Wehrmacht officers and Hitler himself – with avoiding the spectre of an imagined ‘stab in the back’ (of the type allegedly suffered by Germany in 1918); and the contours of what Peifer calls a ‘politicized military leadership’ that propped up the Wehrmacht as a pillar of the Nazi state. The most poignant chapters, however, are those that humanise Hitler’s deserters by, in Peifer’s words, ‘putting a face to the numbers’.

These recount the experiences of eight men who dodged serving under the swastika. Among them is Wilhelm Hanow, who surrendered to authorities two and a half years after going missing from his unit, hidden by a brave wife who herself faced charges for aiding and abetting a deserter. Hanow was guillotined in May 1943. Ludwig Metz crossed the border into Switzerland, where he was questioned by the Swiss Military Intelligence Service, resulting in an unusually rich reconstruction of his path to, and motivations for, desertion. Stefan Hampel, born to a German mother and a Polish father, had contact with a Polish-Lithuanian resistance group while on the run from his unit. His sentence of 15 years of heavy labour was ‘little more than an extended death sentence’; incredibly he escaped from the labour camp only to be taken prisoner by the Soviets. Although, as Peifer rightly points out, there was no ‘typical deserter’, these short biographies highlight a factor that appears to have increased the likelihood of a death sentence in German military trials: the deserter’s supposedly ‘asocial personality’. Peifer thereby reveals just how inextricably intertwined military judicial ‘logic’ and Nazi ideological hatreds were.

The lengthy sections about why the vast majority of German soldiers continued to serve seem less necessary. Information about the ideological training provided by the Hitler Youth, contemporary notions of masculinity, and of comradeship are not entirely out of place, but this is well-trod terrain. Peifer might have been wiser to focus solely on who said no and why, rather than on the ongoing yeses. There are also some errors: Hitler was imprisoned at Landsberg not Landshut, President Paul von Hindenburg becomes Erich von Hindenburg and in some places is misspelled Hindenberg.

Despite this, Peifer deftly categorises the various motivations for desertion, emphasising that war weariness, fear, homesickness, and family issues topped the list, while moral reservations and political motives were much less frequent. Having these findings now available in English is a real service to scholarship on the Third Reich, and Peifer’s book goes further by examining the debates about the role of the deserter in postwar public memory in both Germanys. Maligned by many veterans as a traitor and a coward but later heralded as a hero and even a resister by peace activists, the German soldier who broke his oath to Hitler has been a polarising figure for decades.

That debate continues, playing out not only in academic publications and parliamentary debates but in public spaces. In 2009 in Cologne, a new ‘deserter memorial’ was unveiled, the Memorial for the Victims of NS Military Justice. Words made of metal form a shelter-like structure. They articulate a clear position on the controversial figure Peifer so skilfully depicts. They equate the deserter with a resister who ‘refused to shoot’, ‘refused to kill’, ‘refused to torture’, ‘refused to denounce’, ‘refused to brutalise’, ‘refused to discriminate’, and who ‘showed solidarity and civil courage when the majority remained silent and followed’. Whether the majority of Hitler’s deserters would have identified in this way is unlikely; most, when confronted by a brutal and eventually unwinnable war, simply chose to save themselves.

-

Hitler’s Deserters: Breaking Ranks with the Wehrmacht

Douglas Carl Peifer

Oxford University Press, 312pp, £26.99

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Kristin Semmens is Associate Professor in History at the University of Victoria, Canada. Her latest book is Under the Swastika in Nazi Germany (Bloomsbury, 2023).