Unsettled Legacy

Have dominant narratives of the American Civil War been detrimental to its emancipatory promise?

The southern writer Robert Penn Warren claimed that the Civil War was the United States’ ‘only “felt” history – history lived in the national imagination’. If ongoing debates about the management of Confederate statuary teach us anything, it is that its reverberations continue to be felt by Americans today. The grip of the Civil War certainly seems to have tightened in recent years as the rise of white supremacist violence and the efforts of the Black Lives Matter movement to challenge systemic racism remind us that, as Cody Marrs puts it, the Civil War is an ‘unsettled conflict that will continue to be refought as long as American civilization exists’.

For Marrs, the war’s unsettled legacy is rooted in the stories that soldiers and civilians began telling about it from its very start – and which continue to influence our understanding of the political upheaval and unprecedented death it caused. Historians including David Blight have detailed the battles fought over the war’s commemorative practices. Marrs unravels some of the literary plot lines that emerged alongside Memorial Day observances and monumental dedications, revealing how Americans have attempted to ‘give the struggle shape and meaning’ and exploring why those narratives ‘resonate on various frequencies into the 21st century and beyond’. In the process, he joins numerous literary historians in arguing for the centrality of narrative construction – in poems, short stories, military histories, soldiers’ journals, novels, speeches and visual artworks – to Civil War myth-making. ‘In the United States, regional, national, and political sensibilities have long taken shape through the war and the epic significance that is attached to it’, Marrs writes: ‘whenever we tell a story about the Civil War, we are almost always telling a story about ourselves.’

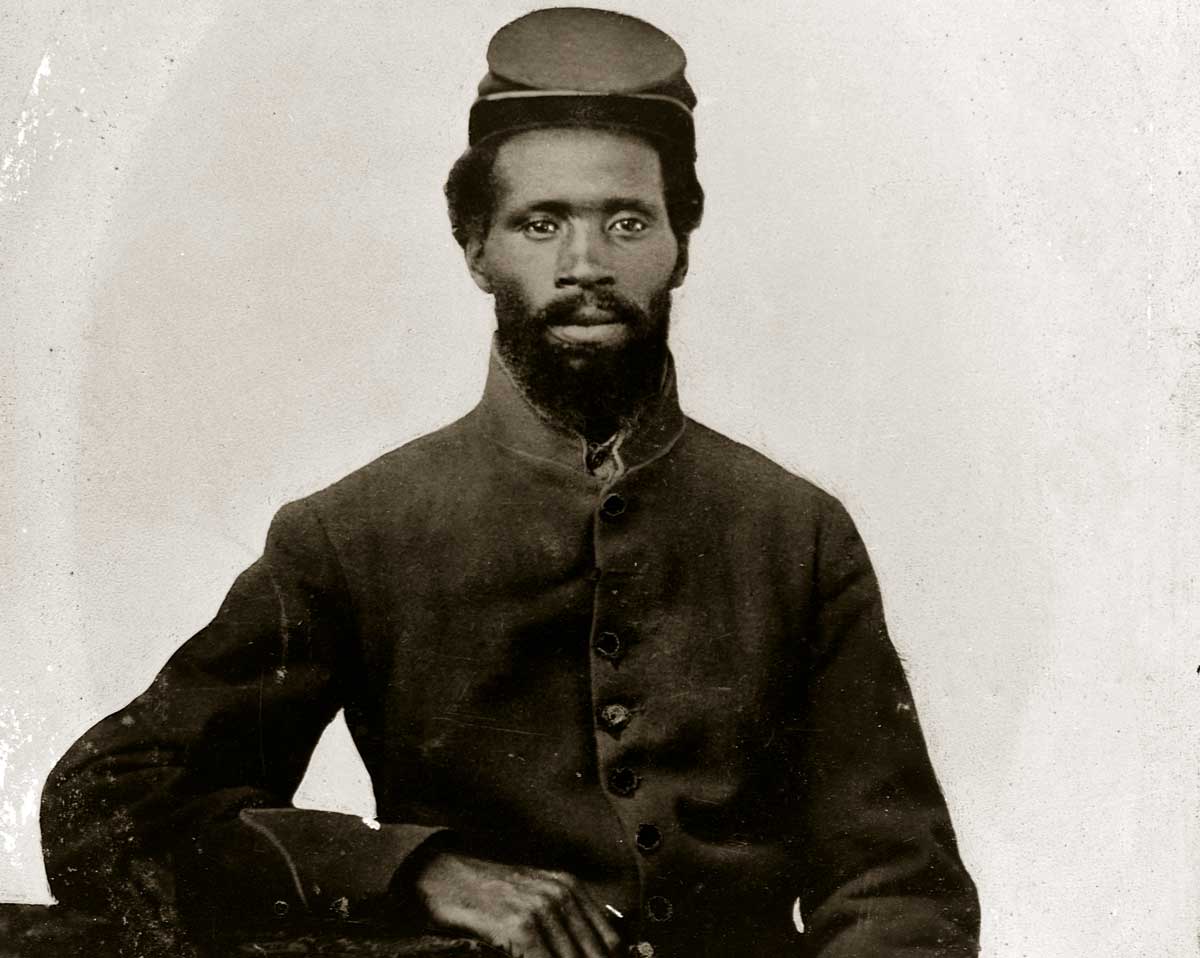

Not Even Past examines four key plot lines, which have become contenders in the war for Civil War memory. Indeed, as Marrs discusses the war’s various narrative manifestations – from the internecine ‘family squabble’ and a ‘dark and cruel’ moment of existential crisis, to the Confederacy’s infamous ‘Lost Cause’ and the narrative, shaped and critiqued by African Americans, of the ‘Great Emancipation’ – he acknowledges how some of these have become culturally dominant, often to the detriment of the war’s emancipatory promise. By explaining how the tropes of the ‘war between brothers’, the war as a history of military strategy (or ‘great men’s actions’) and the war as a struggle for ‘states’ rights’ privilege certain forms of belief and experience, placing ‘white Americans at the core of the conflict’, Marrs asks us to think critically about how such storytelling ‘decenters and devalues black freedom’. And he rightly amplifies the voices of the Black Americans who fought, and still fight, to realise the freedom promised by Lincoln’s Proclamation. One result of his focus, though, is that male voices ultimately prevail, while Emily Dickinson, Margaret Mitchell and Natasha Tretheway – among a handful of women writers featured – make brief cameos. Perhaps this trend is inevitable; but what might be gained from recognising the war’s ‘unofficial’ narratives? How might a woman’s war – white or Black – register in the cultural fabric of the US today?

These questions aside, Marrs’ study is an articulate and extremely accessible introduction to Civil War literary history. Discussing texts by a remarkable range of writers, both familiar and neglected, from Walt Whitman, Mark Twain and General William T. Sherman to William Wells Brown, W.E.B. Du Bois and Michael Shaara, Marrs offers moments of focused insight within an impressive chronological sweep, which records, with due urgency, the ways the war continues to shape US culture. Forthright in its conclusions about the insidious nature of some of these stories, this study is also by turns witty; Marrs has a talent for exposing the more absurd aspects of Civil War mythology and bringing a healthy dose of level-headedness to the proceedings. In this respect, his study rejects irreverence for necessary scrutiny and piercing honesty; it also works, most poignantly, to identify Civil War stories that are emerging even now, stories of ‘real equality’, which bring new futures into view.

Not Even Past: The Stories We Keep Telling About the Civil War

Cody Marrs

Johns Hopkins 226pp £20

Kristen Treen is Lecturer in American Literature at the University of St Andrews.