Portrait of the Portrait Artist

Holbein’s creative life during three decades of extraordinary political, religious and intellectual turbulence.

In Augsburg’s Staatsgalerie Altdeutsche Meister there is a three-panelled painting illustrating the life of St Paul, painted by Hans Holbein the Elder in 1504. Commissioned for the city’s Dominican convent of St Katherine, it includes a self-portrait of the artist with his two sons, Hans and Ambrosius – nicknamed, we know from another source, Hensly and Brosi – as witnesses at the baptism of the saint. We don’t know why, but Holbein the Elder is pointing to the young Hans, as if, aged seven or so, there is already something remarkable about him. It is fitting that this, the earliest evidence attesting to the life of Hans Holbein the Younger, should itself be a painting. And fitting that there should be something opaque about the meaning of his presence in it, because that quality too defines much of his work.

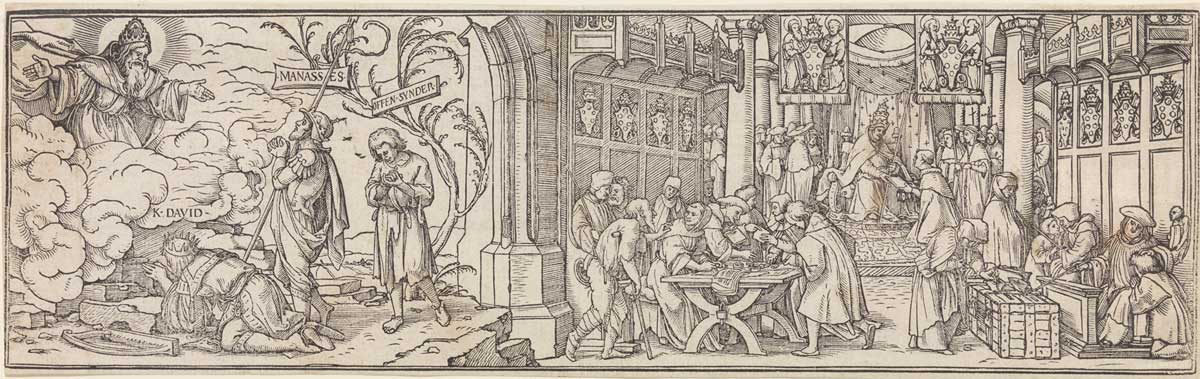

For his father’s generation of artist, as Jeanne Nuechterlein notes in Hans Holbein: The Artist in a Changing World, religious art was the primary source of income. Holbein the Younger, born in 1497 or 1498, was not so fortunate. He began his career at precisely the time that Luther exploded onto the European stage. By 1515 he was in Basel and there he might have stayed had religious images and image-making not been an object of Protestant ire.

Holbein’s own religious beliefs are unknowable. At a time when faith was a critical marker of identity, his is oblique, acquiescent. He was close enough to Erasmus in 1526 for the latter to write him a letter of recommendation to Thomas More in London and for More to welcome him into his home. Yet even some of his early Catholic religious work has a distinctive quality – an apartness – that he carried through to his later secular work.

Take his extraordinary Dead Christ in the Tomb of 1521-22, which strips the conventional religious image of all its theatre, representing a side-on view of the full-length body lain out in what Nuechterlein says is ‘arguably the most explicitly corpse-like rendition of the dead Christ ever made in art’. Is it, as she suggests, an image that acknowledges Reformed critiques of religious image making? Or might it critique de-sacralisation?

In 1530, when the Protestant authorities in Basel investigated the religious conformity of the city’s guild members, Holbein merely asked for clarity about the nature of the Eucharist before falling into line. By then he had already spent two years in London, returning to Basel in 1528 to witness, inauspiciously, a wave of iconoclasm that destroyed much of the city’s religious art. He was in London again by 1533 and it would be his home until his death in 1543. He came to England in search of financial stability; if he sought political stability too, he could hardly have been more disappointed.

Much attention has been paid to Holbein’s career as an artist at the court of Henry VIII. It is these portraits we remember most: exquisitely real, exquisitely inscrutable, but presented with a realism that is, in fact, also highly conditional. Holbein’s goal throughout his career, Nuechterlein argues, was ‘to reproduce worldly appearances in ways that … look entirely persuasive, but which incorporate various departures from reality that he thought made the image more effective’.

Hans Holbein: The Artist in a Changing World is not a biography. Instead, Nuechterlein offers a compelling thematic account of Holbein’s creative life that emphasises the steadiness of his artistic gaze as he navigated three decades of extraordinary political, religious and intellectual turbulence.

Hans Holbein: The Artist in a Changing World

Jeanne Nuechterlein

Reaktion 280pp £15.95

Mathew Lyons is author of The Favourite: Ralegh and His Queen (Constable, 2012).