A Warning from History for the Google Translate Generation

The decline of language skills threatens the study of the past. And machines won’t come to the rescue.

The UK education system is failing to produce enough students with foreign language skills, an indispensable tool for the study of history. Research published in June this year by the Confederation of British Industry revealed that one in five schools in England had a persistently low take-up of languages, after what the government is describing as ‘a decade of damaging decline’. This slump has taken its toll on the university system. In the past 15 years more than a third of UK universities stopped offering specialist modern European language degrees, arguing that rigorous marking at A-level had deterred teenagers from studying languages at school.

The UK education system is failing to produce enough students with foreign language skills, an indispensable tool for the study of history. Research published in June this year by the Confederation of British Industry revealed that one in five schools in England had a persistently low take-up of languages, after what the government is describing as ‘a decade of damaging decline’. This slump has taken its toll on the university system. In the past 15 years more than a third of UK universities stopped offering specialist modern European language degrees, arguing that rigorous marking at A-level had deterred teenagers from studying languages at school.

The same period of time has witnessed the ‘rise of the machine translators’. In 2006 Google launched its pioneering ‘Google Translate’ service, offering instant on-screen translations between English and Modern Standard Arabic. Today Google offers translation services in and out of more than 70 languages, meeting the needs of the monolingual student generation with ever increasing efficiency and popularity. However, the one-dimensionality of machine translation restricts the response of the on-screen polyglot to a singular, literal definition of each word or phrase. Mistranslations across the widest cultural gulfs abound.

The problem lies in the machine’s inability to consider the cultural context that gives each word its meaning

The French idiom se taper le cul par terre, for example, is understood by every Francophone as ‘to laugh heartily’ and has little to do with the literal definition offered by Google – ‘ass banging on the floor’. The dangers inherent in this acultural approach to foreign source material did not begin with the invention of the robotic interpreter. Some of history’s most ambitious translation projects have failed just as miserably to notice or bridge the cultural gap between what is said and what is meant.

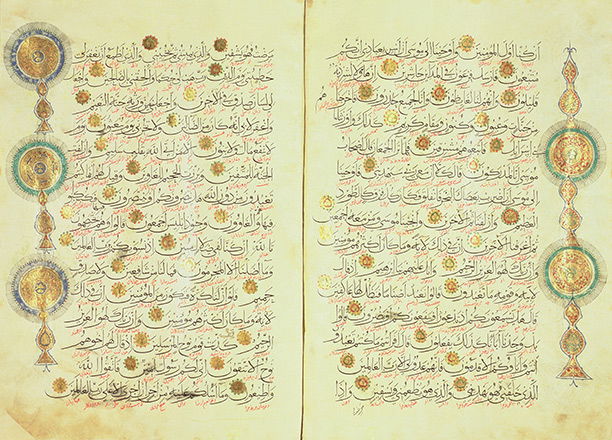

The Christian preoccupation with Muslim belief, which became obsessive during the Crusades, resulted in the first European attempts to make sense of the Quran. Arabic-to-Latin translation services were in no short supply. Centuries of Arab astronomy and mathematics had made Arabic-Latin bilingualism a matter of scientific necessity. Yet, whether out of ignorance or hostility, these early Christian translations were often woefully devoid of cultural understanding. In this most nuanced of subject areas, a singular or literal interpretation is often the most damaging or damning. The first western attempts to make sense of this notoriously complex source, therefore, offer some valuable lessons to the upcoming Google Translate generation.

In the Quranic account of Joseph’s adventures in Egypt, for example, a certain innocuous verse describes the reaction of the Egyptian women to his beauty. In the Arabic original the verb is akbara, for which dictionaries carry a number of definitions primarily associated with the process of ‘honouring’ and ‘glorifying’. Muslim translations therefore converge on variants of ‘when they saw him they all admired him’ or ‘when they saw him they all praised him’. However, when Robert of Ketton, the first to translate the Quran into Latin, came across this word in 1143, he scrolled through his lexicon with all the blinkered literalism of an automated translation service. Selecting a definition seemingly at random, he found that the verb akbara could also be used to describe an unrelated physiological process. The first Latin translation thus became quo uiso omnes menstruatae sunt (‘when they saw him they all menstruated’), a literal but improbable interpretation.

One of the Quran’s more controversial verses mentions a ‘spirit’ sent by God to assist Jesus: ‘We gave Jesus clear signs and supported him with the spirit of sanctity’. The ‘spirit of sanctity’ (rūh al-qudus) is easily associated with ‘the Holy Spirit’ (spiritus sanctus). Indeed, translating the passage with Google today will yield exactly this result. The problem with this translation is the uniquely Christian sentiment that it conveys. The predominant Muslim belief is that New Testament notions of God as ‘Father, Son and Holy Spirit’ undermine the singularity of Abrahamic monotheism. Muslim translators, therefore, commonly refuse to translate rūh al-qudus as ‘the Holy Spirit’, favouring instead variants on ‘holy inspiration’ or ‘divine grace’. Yet in 1210 Mark of Toledo, the second Latin translator of the Quran, automatically selected the words spiritus sanctus and thereby forced the Trinitarian theory into the mouth of its loudest critic with the same misleading literalism as can be found on Google to this day.

Another problematic Quranic verse describes what appears to be Islamic reincarnation. Literally, the verse reads: ‘How can you not believe in God? For when you were dead, he gave you life.’ The idea that God brought us into life from a state of death (after, presumably, a previous life) conflicts fundamentally with the Islamic belief in one life according to which we are judged in the hereafter. The tendency among Muslim translators of the verse is, therefore, to avoid a literal reading of the words ‘you were dead’ at all costs, favouring instead words like ‘you were nothing’, ‘lifeless’, or ‘without life’. Yet when Ludovico Marracci, the last Latin translator of the Quran, came across this passage in 1698, he automatically offered the literal interpretation, rejected by the Muslim tradition, in which God brings us into life from death: fuistis mortui (‘you were dead’). He thereby proposed a culturally misleading, reincarnationist revision, which would continue for the next 250 years of non-Muslim Quran translation.

The ‘rise of the machine translators’ therefore began long before the machine. Indeed, it should now be said that although, like Google Translate, these translators can rarely be faulted on their interpretation of individual words, their purpose was largely to facilitate Christian refutation and ridicule of the Quran. Wilfully read at its most literal level, the Quran was falsified into a Trinitarian extension of the New Testament, with some novel ideas about life after death and Joseph’s effect on womankind.

These interpretations would thus provide ample fodder for generations of anti-Islamic Christian scholars, who felt no need to study Arabic themselves because literal Latin translations of the Quran were readily available. When in 1311 the Council of Vienna established language schools in Paris, Bologna, Oxford, Salamanca and Rome to educate monks in Quranic refutation, their principle source for the doctrines of Islam was Robert of Ketton. Indeed, when the Latin Quran came into print during the Reformation, it was this translation that was published, complete with a horrified marginal annotation beside his adaptation of the Joseph story: o foedum et obscoenum prophetam (‘Oh the filthy and abominable prophet!’). Christian scholars seized upon the Holy Spirit’s unexpected cameo in Mark of Toledo’s Latin Quran, arguing that the text itself validated the Trinitarian doctrine and contradicted what Muslims themselves believed.

The Church’s most powerful weapons against Muslims off the battlefield were these selective literal interpretations of their written culture. The ‘decade of decline’ in language learning and the generation of Google translators it produced threaten our understanding of foreign cultures in just the same way. By exploring foreign source material in a cultural vacuum, the Google Translate generation risks straying just as irretrievably from the message behind the meaning behind the words. In an age of instant transnational communication, it is our ability to communicate across cultural divides that separates us from the machine translators.