Colonial Projections

Studying African history through the lens of cinema.

Walking on the Island of Mozambique last November, facing the Indian Ocean, I came upon a relic of a lost past. The Cine Teatro Nina was an imposing building, with wide front steps and pillars supporting a stone veranda, but it was now abandoned, unused for a long time. Once, social lives were shaped here. The romances, disputes and passions that had been raised within were now gone.

In fact, as Odile Goerg’s new book shows, places like the Cine Teatro Nina were central to the urban landscape of colonial Africa. Across Africa, towns ‘became towns’ – as one of her interviewees put it – when they had cinemas. These were places in which authorities sought to control colonial subjects through censorship and where those subjects formed their own modern urban identities regardless. Studying African history through the lens of cinema, Goerg shows how cultural approaches can offer important new insights to the colonial past.

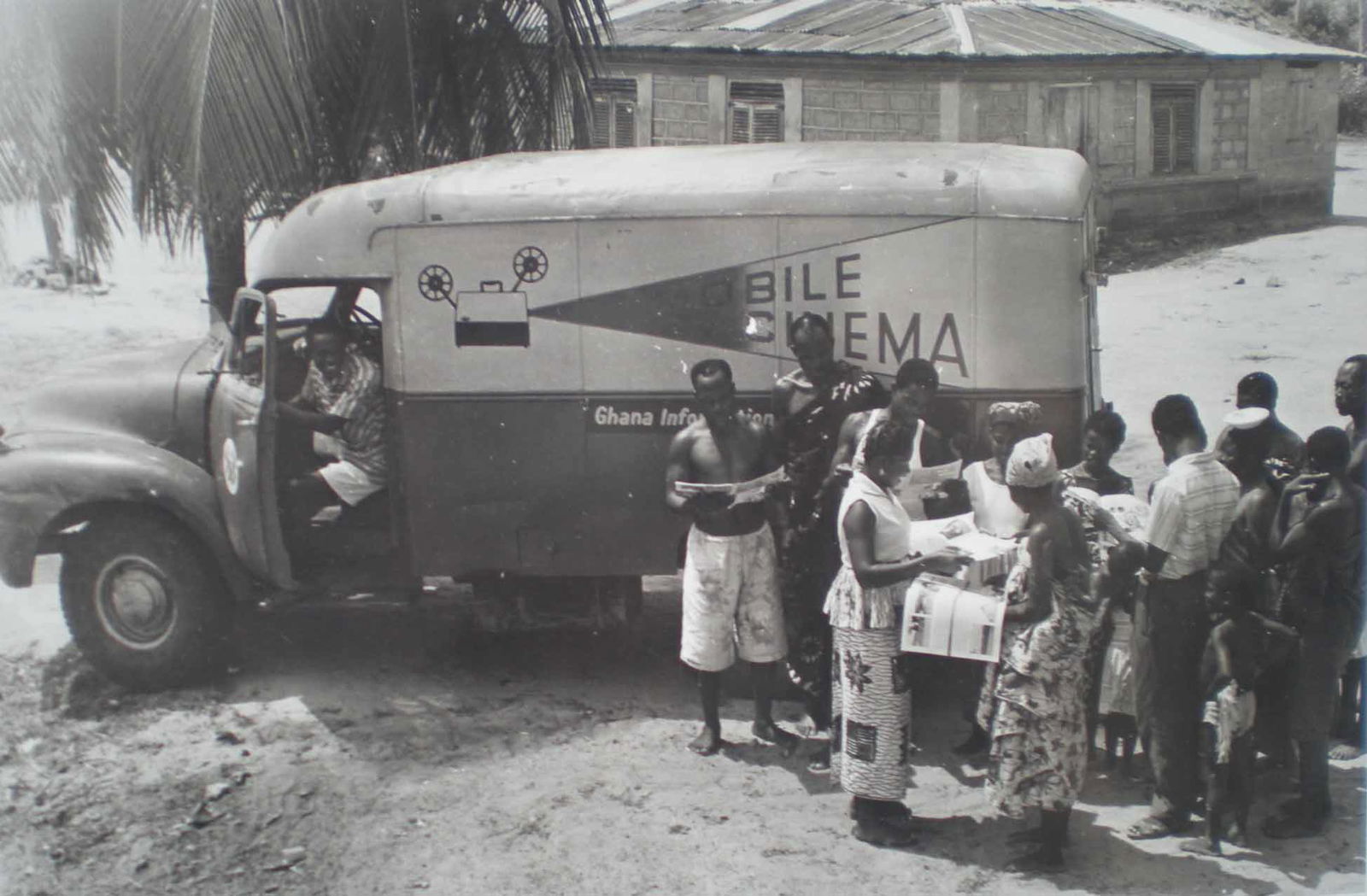

Goerg’s book takes us from the early 20th century to the rise of African nationalism. Her interests range widely, from the mechanisms of colonial censorship and the techniques of assemblage and projection, through to the social arena of the cinema and the impact of the mobile cinemas which toured rural West Africa until the late 1950s. This range provides a vivid and memorable impression of Africans in both urban and rural settings in the process of rapid self-transformation.

As everywhere, cinema was an economic activity and the films shown reflected the concern of both West African and European entrepreneurs to turn a profit. Cinemas became locations of class assertion, as elites in places such as Accra increasingly snubbed the medium as ‘for the masses’. The economic dynamism of the sector is fascinating, with West African and European entrepreneurs rubbing shoulders with Lebanese investors and an Ivoirien Islamic preacher who developed a chain of cinemas in the 1950s.

The book’s approach to the moving image from a colonial perspective offers some fresh insights on the ‘seventh art’. If cinema is a window for the self-expression and self-realisation of cultures in the era of mass reproduction, how does that artform appear, then, through the lens of colonial power imbalances?

It turns out that there is not a single answer to this question. Racist presuppositions were never far away, however. Films were produced ‘for the [imagined] African market’, while racist films about Africa for the metropolis were not distributed to this market. Settler colonies such as Northern Rhodesia and Angola imposed segregated seating, whereas in Dakar and other settings with a Western-educated African elite segregation was imposed – as in the West – through class and the economic cost of the ticket.

The ability of colonial powers to enforce control broke down after the end of the Second World War. Censorship lost ground in the face of the enormous increase in film production and the demands of the new nationalist elites eager to take the reins of power as independence loomed. With independence, African cinema entered a golden age of directors such as Ousmane Sembène, which lasted through to the 1980s. But over time the cities exploded and urban distances mushroomed. The difficulty of accessing cinemas such as the Cine Teatro Nina meant they fell into the decay, chimeric fantasies that characterised the colonial project.

Tropical Dream Palaces: Cinema in Colonial West Africa

Odile Goerg

Hurst 201pp £45

Toby Green is the author of A Fistful of Shells: West Africa From the Rise of the Slave Trade to the Age of Revolution (Allen Lane, 2019).