‘Heimat: A German Family Album’ by Nora Krug review

The question of the responsibility of the ‘everyman’ and ‘everywoman’ remains a pressing one in Heimat: A German Family Album by Nora Krug.

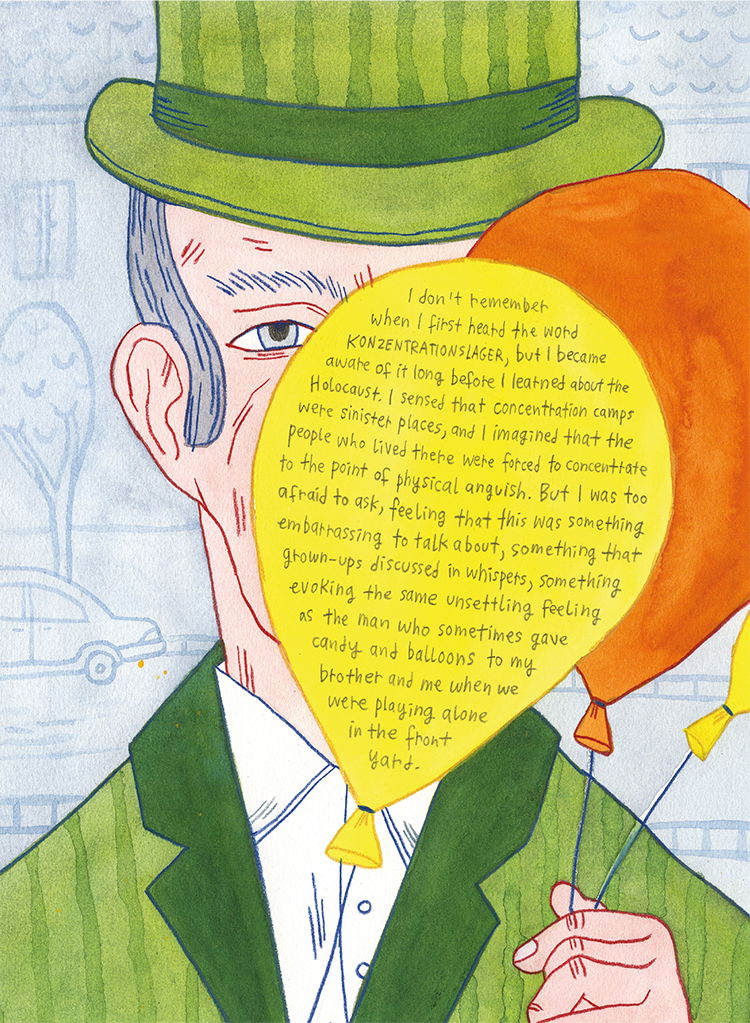

Growing up opposite a US military base in Karlsruhe, Germany in the 1980s, Nora Krug knew that something ‘had once gone terribly wrong’. She and her classmates would use certain words, without fully understanding their meaning. A Konzentrationslager, for example, was sinister and ominous, but as a child she imagined it as a place where people were ‘forced to concentrate to the point of physical anguish’.

Growing up opposite a US military base in Karlsruhe, Germany in the 1980s, Nora Krug knew that something ‘had once gone terribly wrong’. She and her classmates would use certain words, without fully understanding their meaning. A Konzentrationslager, for example, was sinister and ominous, but as a child she imagined it as a place where people were ‘forced to concentrate to the point of physical anguish’.

Krug’s inchoate knowledge of Germany’s wartime history meant that asking her parents questions often led to confusion. She caused her mother alarm when, returning from school, she asked: ‘Are Jews evil?’ Later, travelling the world as a teenager before moving to the US, Krug felt ashamed of her nationality and heimatlos – without a place she could consider home.

Krug associates the burden of shame experienced by many of her postwar generation with the German equivalent of original sin – inherited sin. Visiting church as a child, she promised Jesus that she would bear the consequences of the previous generations’ actions. Now in her thirties, living in New York and married to a Jewish man, Krug channels the unease felt by her generation in a more productive manner, with a frank exploration of her family’s actions during the war. This stunning graphic memoir is the result.

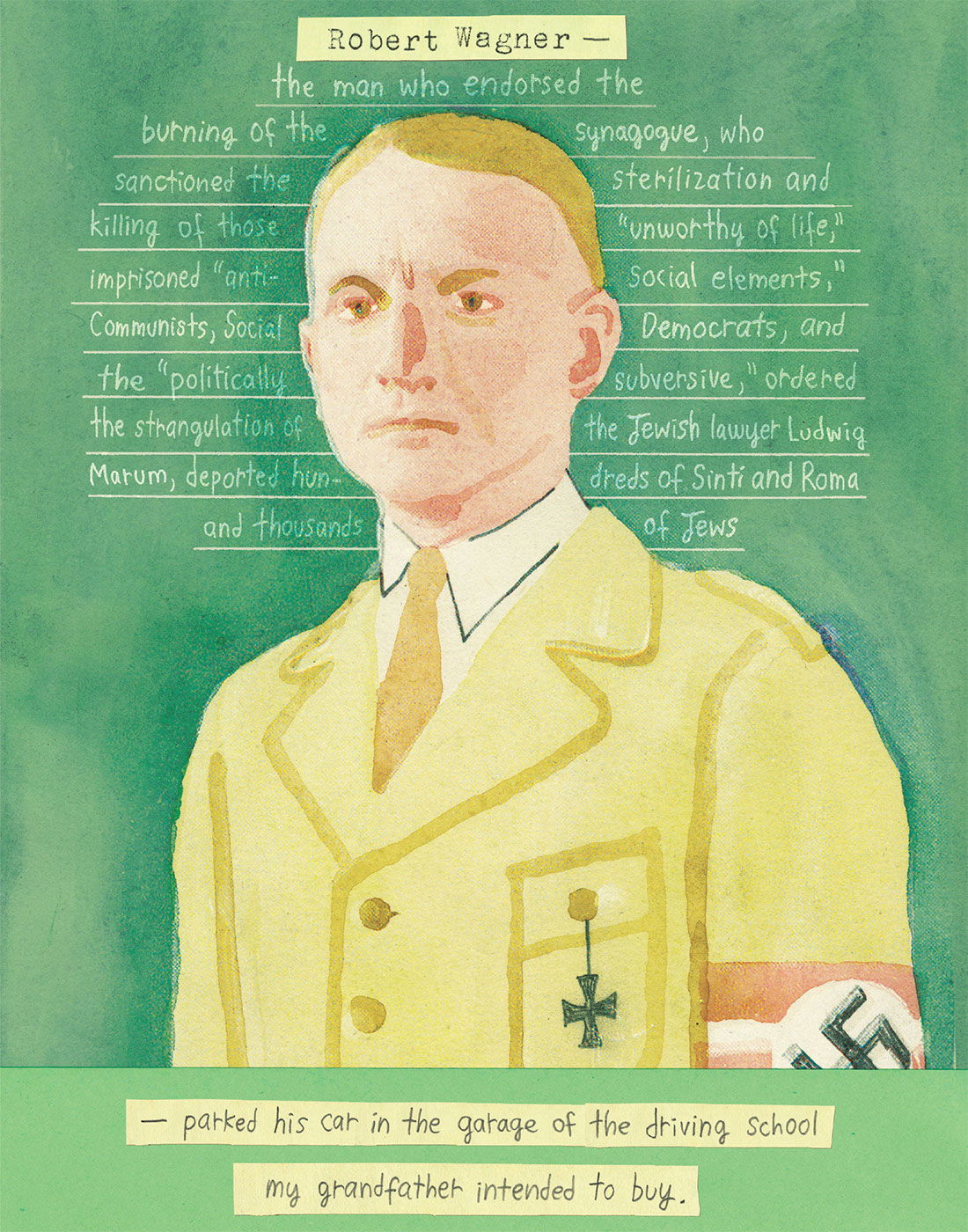

Heimat unravels like a murder mystery in which the detective hopes to catch the perpetrator, but does so knowing that they themselves will have to live with the repercussions. Krug’s quest, diarised in meticulous handwritten pencil, is documented with distinctive drawings (reminiscent of a children’s picture book), scans of letters and government papers and collages of photos and objects found in flea markets. It includes a copy of her soldier uncle’s primary school homework book in which he receives a grade ‘B’ for his story, ‘The Jew, a Poisonous Mushroom’, as well as photos taken by her grandfather that cast doubt on the family story that he hid his Jewish employer in his mother-in-law’s shed.

‘It takes far less courage to consult the vaults of an archive than to talk to one’s distant aunt’, Krug writes of her experience reaching out to family members. Often, they are not as ready as she to confront the past. In drawn scenarios, Krug tries to map her family’s day-to-day lives during the war. Did they have a radio? Would they have known what was happening? She studies photos, trying to spot relatives at events perpetrated against the Jewish community in Külsheim, her father’s hometown. Were they there, out of sight of the lens?

Krug finally discovers a document proving that her grandfather was a member of the Nazi party. But this brings no closure. Many Germans were forced to join. In a postwar questionnaire, he claimed he had no rank or dealings with the party. He describes himself as a Mitläufer (‘follower’) – ‘a person lacking courage and moral stance’. Krug imagines her grandfather pleading guilty to his ‘weak-mindedness’ and illustrates the page with a drawing of a sheep.

Were members of her family responsible for the mistreatment and murder of Jews in their town, country, continent? Krug’s findings are inconclusive. The question of the responsibility of the ‘everyman’ and ‘everywoman’ remains a pressing one. But despite her ambiguous conclusion, Krug’s fervent, unflinching research into family documents and archives is inspiring. Her exploration of inherited shame reminds us that antisemitism and prejudice are not confined to history. In Heimat, she shows us that ignorance is a tainted kind of bliss.

- Heimat: A German Family Album

Nora Krug

Particular Books

288pp £22

Jen Calleja is a writer and literary translator from German. She was the inaugural Translator in Residence at the British Library.