‘A Literary Tour de France’ by Robert Darnton review

A professionally organised covert industry satisfied the public’s demand for illicit books in the years before the French Revolution.

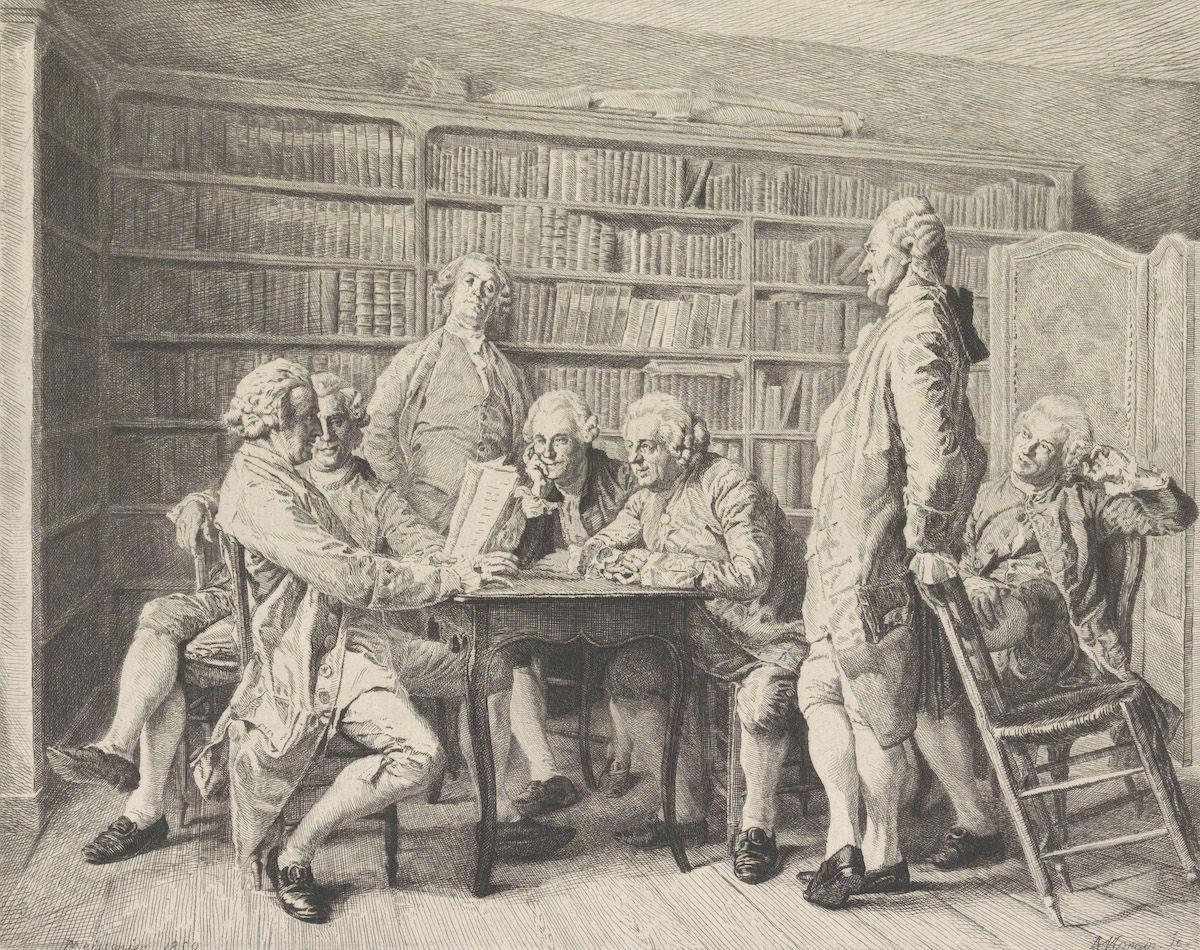

In Robert Darnton’s hands the accounts and letters of the Société typographique de Neuchâtel (STN) become an eye-opening story of how foreign publishers smuggled forbidden and pirated books into France between 1769 and 1789. Paris firms had a stranglehold on the nation’s publishing, reinforced by state edicts suppressing ‘subversive’ works. An illicit industry satisfied the appetite of readers for all kinds of writing, sanctioned or not.

Covert networks were extensive and professionally organised. From Amsterdam to Avignon, publishers not constrained by the laws of the ancien régime, let alone copyright, delivered books across France. Darnton follows the picaresque progress of one of the STN’s travelling salesmen, Jean-François Faverger, who journeys for five months in 1778, from Lyon to Marseille to Bordeaux, Orléans and Besançon and back to Neuchâtel. His mission is to discover which booksellers inspire confidence (the scale is ‘good’, ‘mediocre’ and ‘not good’), encourage orders, collect debts and undercut rivals. He contends with filthy inns, scabies, muddy roads, a lame horse and duplicitous clients, dutifully returning reports to his employers.

The STN’s catalogue of 300 titles included religious works, Enlightenment writings (Rousseau, Voltaire, Diderot’s Encyclopédie), authors such as Laurence Sterne, history and geography, science and medicine, libels about the court of Louis XV and pornography (Cleland’s Fanny Hill becomes La Fille de joie, classified under the heading of livres philosophiques). The STN did not issue such works, but could supply titles through exchange with other publishers. Its motive was to make money.

In this ferment, risk vies with caution and supply pursues demand. But deeper struggles surface. The STN was a Protestant organisation, using networks of Huguenots to further its business interests. Some of its books promoted the rational, anticlerical ideas of the Enlightenment, to which Protestants were receptive. Again, in 1781 the crisis at court provoked a spike in demand for the report of Jacques Necker, the former finance minister, on the state of the economy. The STN was happy to oblige.

Banned or pirated books were shipped in 50lb bales of unbound sheets, hidden among innocuous publications and carried across mountain passes. The process was overseen by passeurs, who guaranteed safe passage or ‘insurance’. At the French border, naïve or corrupt officials waved the contraband through, while the more conscientious stopped it in its tracks. With greater regulation and then the Revolution the STN collapsed. Faverger switched his energies to more dependable commodities: wine and groceries.

Darnton has mined the STN and related archives since 1965. This book is a tribute to determination, scholarly precision, interpretation and a sharp eye for human foibles.

- A Literary Tour de France: The World of Books on the Eve of the French Revolution

Robert Darnton

Oxford University Press

376pp £25.49

Peter Brown is Academic Director of the University of Kent’s Paris School of Arts and Culture in Montparnasse.