‘Threads of Global Desire’ review

The story of silk, which connected the world with a thread.

As this erudite volume makes clear, silk connects, communicates and challenges our assumptions about luxury and consumption. In the introduction, the editors explain why they have focused on ‘a liquid extruded by a caterpillar [which] upon contact with air … solidifies into a filament’. The results, they argue, form the basis for a remarkable story of wealth and power, ‘transforming economies and societies’.

To understand this story across time and space, three scholars organised an international conference almost a decade ago. This brought together specialists in silk cultivation, spinning, weaving, trade, design and use from across Europe, Asia and the Americas. Long in the making, the published results are fascinating. While it will be tempting to dip in and out according to specialist interests, it is well worth reading the whole book as an exercise in comparative history and material culture.

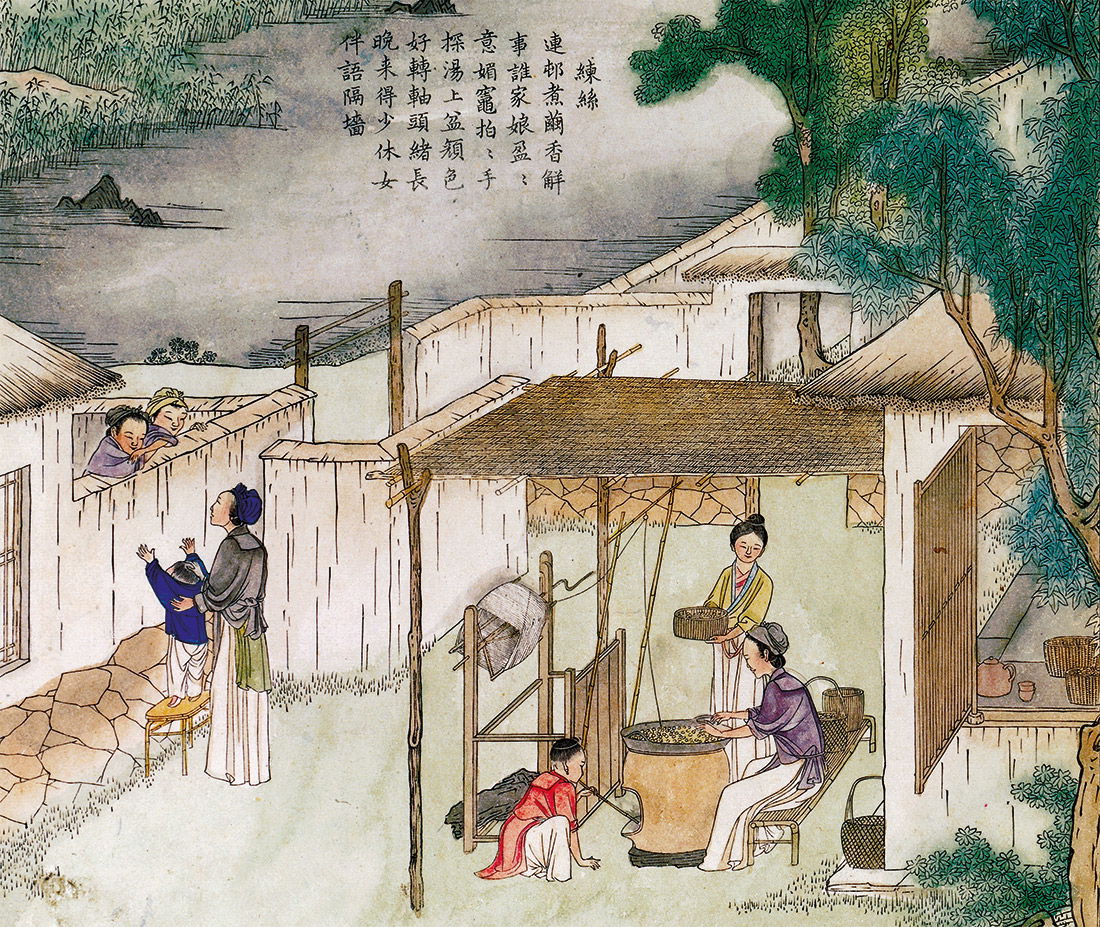

So what do we learn from this volume? First, that silk has an extraordinarily long history dating back in China to at least the third-century BC Han dynasty. Far from being ubiquitous, it was the very difficulties of its cultivation and production that made silk such a rare commodity. Silk was not something that spread with ease: it was not addictive like tobacco or mildly stimulating like coffee; it could not be planted throughout the colonies like tea or picked like cotton. Instead, raising mulberry trees and silk worms demanded a particular climate and labour supply, while creating threads and cloth required skills, technology and significant capital investment. Knowledge, labour and experience were stolen, exchanged and bartered, which made workers in the silk industry as mobile as the products themselves.

How did this industry become a global one? Divided into three parts, the book’s experts look first at silk’s Asian origins, then at European developments and finally at global exchange. All three sections take a broad chronological approach, but the majority of essays focus on the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. This was a period of expanding maritime travel, trade and colonialism (topics are covered from the perspective of China, Europe, Japan, the Ottoman Empire, New Spain and North America, as well as through the lens of the Dutch and English East India Companies). It was also a period when fashions were in flux. It is valuable to read about the role that silk fabrics played in Japan alongside chapters on the ribbon supply in Restoration England; such a comparison puts to rest the traditional suggestion that there was little, if any, fashion innovation in Asia.

The chapters on the trade between Mexico and China are similarly nuanced, demonstrating that Latin American consumers understood the differences between local silk products and imports, valuing both for different purposes.

Many of the chapters focus on the specific circumstances of silk production or consumption in particular moments and places. However, in the last chapter, one of the editors, Giorgio Riello, provides a thoughtful and sometimes provocative overview that brings the volume to a close. Drawing on some of his earlier work, he divides the globe into three ‘textile spheres’: wool, cotton and silk. In doing so, he demands that we consider not only trade routes and new technologies, but also where the textile itself came from (animal, insect or plant), how it was made and by whom and, above all, its aesthetic and tactile qualities.

The book’s illustrations, ranging from Ming dragon robes, Ottoman cushion covers and an Italian priest’s robe to woven banyans from Spitalfields, also reinforce the importance of silk’s special sensory nature, a reminder that it was the sight, sound and, above all, the feel of silk that made it such an important signifier of luxury and desire.

- Threads of Global Desire: Silk in the Pre-Modern World

Dagmar Schäfer, Giorgio Riello and Luca Molà (eds)

The Boydell Press/Pasold Research Fund

447pp £60

Evelyn Welch is Provost (Arts & Sciences) and Professor of Renaissance Studies at King’s College London. She is currently running a project on Renaissance skin, renaissanceskin.ac.uk.