Alexander: Cross-Dressing Conqueror of the World

Oliver Stone’s 2004 film Alexander portrayed the great Macedonian king as bisexual. Was he also a transvestite? Tony Spawforth looks to uncover the truth.

This startling claim was made by a contemporary Greek, Ephippus, in his lost pamphlet depicting Alexander’s court in the last two years of the reign (324-323 BC). In a surviving fragment Ephippus alleges that the king liked to cross-dress as Artemis, the Greek archer-goddess of the hunt. Supposedly Alexander often appeared in her guise ‘on his chariot, dressed in the Persian garb, just showing above his shoulders the bow and the hunting-spear’.

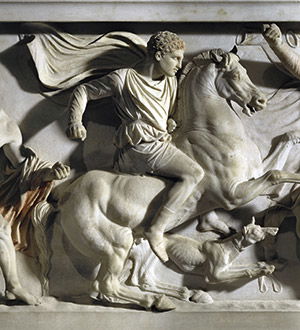

Chariot and bow were stock attributes of Artemis in Greek art but she did not wear ‘Persian garb’. Remarkably, Alexander did. Xenophobic Greeks routinely derided Persian costume as womanly. A sardonic Ephippus was put in mind of the Greek iconography of Artemis when he saw Alexander in his Persian robes going out to hunt on a chariot and armed with a bow.