Jaipur’s Last Stand

The new government of an independent India sought to curtail the influence of the old princely order. When the Maharani of Jaipur entered politics in 1962, it had a popular problem to contend with.

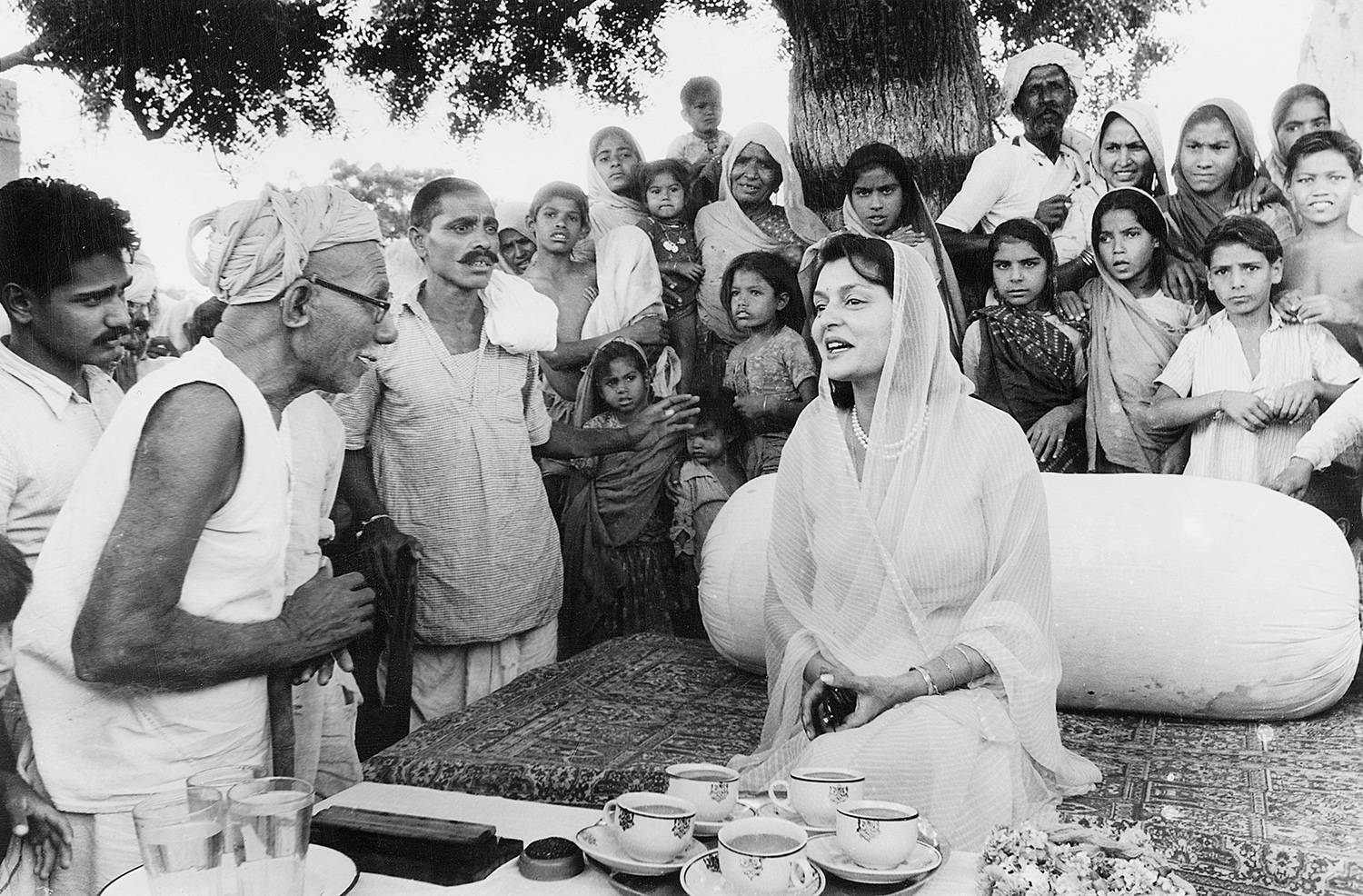

Gayatri Devi with villagers in Rajasthan during her election campaign in 1962.

Jawaharlal Nehru never hid his contempt for India’s royalty. The nation’s first prime minister loathed the ‘gilded and empty-headed maharajas and nawabs who strut about the Indian scene and make a nuisance of themselves’. To convince more than 550 princes to join an independent India, Nehru grudgingly allowed them to retain their titles, privileges and privy purses, but by the 1960s such dispensations were viewed as anachronistic.

Nehru’s daughter Indira Gandhi became prime minister in 1966. She inherited her father’s dislike of the princely order, believing it to be ‘incompatible’ with ‘the spirit of the times’. Her loathing was coupled with fear. India’s royals had lost little of their lustre and those with the audacity to enter politics were successfully taking on her Congress Party.

Of all those she despised, she held Gayatri Devi, the Rajmata of Jaipur, in most contempt. As the writer Khushwant Singh eloquently observed: ‘Indira could not stomach a woman more good-looking than herself and insulted her in Parliament, calling her a bitch and a glass doll. Devi brought the worst out in Indira Gandhi: her petty, vindictive side.’

In 1962 Devi made her first foray into politics, contesting the seat of Jaipur for the Swatantra Party. She won the biggest majority in a democratic election, earning a place in the Guinness Book of Records.

It was an extraordinary performance for Devi, who had swapped her liberal upbringing in the small but progressive state of Cooch Behar in eastern India for ultra-conservative Rajput society when she married Sawai Man Singh, the Maharaja of Jaipur, in 1940. Used to continental excursions, horse riding and hunting – she shot her first panther at the age of 12 – Devi was forced into purdah as Man Singh’s third wife. Her rebellious spirit sat uneasily with such strictures and within a few years she had established a school for girls and was accompanying her husband on his annual trips to Europe.

Ayesha and Jai, as they were known to their friends, soon became India’s ‘golden couple’, its answer to John and Jackie Kennedy or Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip. In the 1930s, Jai had set the sporting world ablaze as captain of the most successful polo team of its day. Ayesha combined the exotic allure of the East with the sophistication of Western aristocracy. Vogue named her as one of the most beautiful women in the world.

They entertained their western friends as lavishly in London, New York and Paris as in their palaces, forts and hunting lodges in Rajasthan. They were the only Indians invited to Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball in 1966 at New York’s Plaza Hotel and Ayesha was the only woman who was permitted to break the dress code, arriving in a gold sari and a necklace of emeralds. Frank Sinatra, Rose Kennedy and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor were there, too. All were friends of the Jaipurs.

In 1957, Jai sounded out the Congress chief minister of Rajasthan about a role for Ayesha. He recognised his wife’s political aspirations but misread her allegiances. Congress, she told him, had been a great party when Mahatma Gandhi was at the helm. But having won power, ‘it was attracting people who were more concerned with a lucrative career than with achieving good for India’.

In early 1961, Ayesha accepted an offer to stand as a candidate for the free-enterprise Swatantra. The official announcement that she had joined the party was delayed because of Queen Elizabeth’s impending visit to India. The royal tour, which included a stop in Jaipur, put the Nehru government on edge. India was an independent nation; the last thing it wanted was a princely pageant that harked back to the colonial era.

As feared, the royal visit to Jaipur stole the limelight. A correspondent for Tatler described the sight of the Queen riding an elephant into the Pink City as ‘unforgettable’. Some 700 noblemen attended a durbar for the royal couple ‘attired in the court dress of the time of Sawai Jai Singh, the eighteenth-century ancestor of the present Maharaja’. The spectacle left the home affairs ministry in Delhi fuming.

Not all the publicity was positive. When an official photograph showing a nine-foot, eight-inch tiger shot by Prince Philip was released by Buckingham Palace, an Indian government spokesperson branded it ‘astonishing’. Jai had organised 200 beaters to lure the tiger to a position where the Prince was able to mow it down from the top of a 25-foot-high hunting platform. The Mirror condemned the Royal Family for not recognising ‘the modern enlightened view on the killing of animals for pleasure’.

On the election trail, Ayesha proved a star campaigner, despite her limited command of Hindi. She travelled from village to impoverished village in her 1948 Buick, switching to an open jeep where there were no proper roads. ‘Not in the fourteen years of Indian independence has there appeared a candidate with her aura and appeal,’ gushed a correspondent for Time. ‘She is rich, beautiful, intelligent, and a first-rate politician … The Maharani represents the most striking example so far of the return of India’s one-time ruling class to national politics.’

Ayesha repeated her success in the 1967 and 1971 elections, only to watch helplessly as Indira Gandhi used her parliamentary majority to change the Constitution and abolish the privy purses, sounding the death-knell for India’s centuries-old princely order.

Yet such populist measures failed to stem the Congress Party’s disastrous slide in the polls and when an Allahabad court found Gandhi guilty of electoral fraud in 1975 she responded by declaring the Emergency. Thousands of journalists, trade unionists and politicians were thrown into jail – including Ayesha and her stepson Bhawani Singh (Bubbles), who had become the Maharaja of Jaipur after Jai’s death in 1970.

Ayesha’s ‘crime’ was breaching India’s foreign exchange regulations. During a tax raid on her properties in early 1975, inspectors had found some loose change in foreign currency. If not for Gandhi’s personal enmity, such a trifling misdemeanour might have gone unnoticed. Instead, Ayesha found herself mixing with petty criminals in Tihar Jail.

Louis Mountbatten, one of Jai’s closest friends, lobbied for her release, while friends sent jars of Beluga caviar and Fortnum and Mason Christmas cakes. Ayesha’s failing health and a promise that she would refrain from participating in politics led to her release in January 1976 after six months of imprisonment.

Having banded together during the Emergency, the House of Jaipur became a house divided with the three branches of the family going to war over who should inherit Jai’s vast estate. As costly and convoluted litigation span out of control, Ayesha failed to use her position as the family matriarch to seek a compromise. When Bubbles ran for Congress in 1989, she actively campaigned for his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) opponent. Today the family is beset with allegations of forged wills, doctored share certificates, non-disclosure of assets, treasures gone missing and sick or senile people being made to sign away their fortunes. Some cases have reached India’s Supreme Court.

Ayesha left behind a complex legacy when she died in May 2009, aged 90. Critics blamed her for spending more time cultivating her rich and aristocratic friends in the West and defending feudal privileges than fighting for her constituents. Others laud her decade-long stint in politics and her work promoting women’s education and welfare. Few, however, would dispute that when it came to sheer force of personality, she had few peers.

John Zubrzycki is author of The House of Jaipur: The Inside Story of India's Most Glamorous Royal Family (Hurst, 2021).