A History of Haggis

The origins of haggis are as mysterious as the Loch Ness Monster.

In 2009, the world of haggis was rocked by controversy. While most of us might think of it as the quintessentially Scottish dish, Catherine Brown, a Glasgow-born food historian, claimed to have discovered a cookery book from 1615 ‘proving’ that the ‘great chieftain o the puddin’ race’ was actually an English invention. Her fellow Scots were outraged. There was no way a Sassenach could have come up with such braw fid, they growled. As one Edinburgh haggis-maker scowled: ‘I didn’t hear of Shakespeare writing a poem about haggis.’

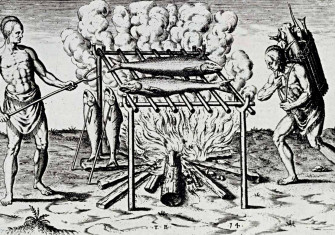

So who is right? It’s hard to say. Haggis’ origins are shrouded in mystery. There is no telling where – or when – it came into being. Some believe that it was brought over by the Romans. Although evidence is scarce, their version – made from pork – probably began as a rudimentary means of preserving meat during hunts. Whenever an animal was killed, the offal had to be eaten straight away, or preserved. This wasn’t an easy thing to do in the middle of a field or forest, so the offal was simply chopped up, packed in salt, stuffed into the animal’s stomach or wrapped in caul fat and then boiled, sometimes in a rudimentary basin made from the hide. It wasn’t pretty, but it lasted for a couple of weeks – and ensured that nothing went to waste.

Others think that a similar type of proto-haggis may have been imported from Scandinavia by the Vikings at some point between the eighth and 13th centuries. In support of this, the Victorian philologist, Walter Skeat, suggested that the root, hag, may have been derived from the Old Norse haggw or the Old Icelandic hoggva – both of which mean ‘to chop’. As such, the name would have meant something like ‘chopped up stuff’ and referred to the method of preparing the offal before it was stuffed into the stomach or caul.

Others still claim it as a French innovation. As Walter Scott pointed out, hag is also surprisingly similar to the French verb hacher, which – like haggw/hoggva – means ‘to chop’ or ‘to mince’. Given the historically strong relationship between France and Scotland (the so-called ‘Auld Alliance’), it is possible that some sort of precursor – not dissimilar to the modern crépinette – might have been brought over at some point after c.1295.

But none of these theories is particularly compelling. At root, they are all based on speculation. Given that sausage-like dishes are found throughout Europe from a fairly early date, it is just as likely that the earliest form of haggis (the ‘ur-haggis’) emerged somewhere in the British Isles. Where, however, is uncertain. If it was made with sheep byproducts, as it is today, then it could have been prepared almost anywhere – and at any time.

An English ‘puddynge’

The earliest references to a dish recognisably similar to haggis come from England. It is first glimpsed – dimly – in The Forme of Cury (c.1390), a rudimentary cookery book written by ‘the Chief Master Cooks of Richard II’. Though a far cry from modern haggis, the recipe for raysols called for grated meat to be cooked in a pig’s caul; and was evidently thought enough of a delicacy to grace the royal table. Some 40 years later, the word ‘haggis’ (or ‘Hagws’) made its debut in a Middle English recipe. Again, this was a rather rich dish, featuring the womb of a sheep, rather than the stomach; but nevertheless made use of a similar technique to that of its modern descendent:

Take þe Roppis [guts] with þe talour [tallow], & parboyle hem; þam hakke hem small; grynd pepir, & Safroun, & brede, & ȝolkys of Eyroun, & Raw Kreme or swete Mylke: do al to-gederys, & do in þe grete wombe of þe Schepe, þat is, the mawe; & þan seþe hym an serue forth ynne.

‘Hagas’ also features in the Promptorium parvulorum (c.1440), a bilingual English-Latin dictionary attributed to Geoffrey the Grammarian, a Norfolk friar. No recipe is given, but it is defined, for the first time, as a ‘puddynge’ – and was almost certainly made of sheep, given their importance to the local economy. And given Geoffrey’s background, there is no doubt that haggis was enjoyed by ordinary folk – as well as by kings.

We should, however, be careful of reading too much into these texts. That they all come from England does not necessarily mean that haggis was invented in England – or that it was unknown elsewhere in the British Isles. Given that a further recipe is found in the Liber cure cocorum, produced in Lancashire at some point in the mid-15th century, there can be no doubt that it was eaten in the north of England; and since the ‘border’ with Scotland was then rather fluid, it is not inconceivable that it was also enjoyed north of the Tweed.

So much, however, is conjecture. Not until c.1513 is haggis attested in an identifiably Scottish text. It appears, albeit fleetingly, in a verse by William Dunbar, a poet associated with the court of James VI. But even then, there is no sense of it being claimed as a distinctively Scottish – or even English – dish. It was just something people ate.

For the next century or so, haggis remained a culturally non-specific food. As Catherine Brown has rightly pointed out, it is found in Gervase Markham’s The English Huswife (1615), a decidedly idiosyncratic book of recipes and remedies, which went on to become something of a bestseller. It also features in Thomas Hobbes’ translation of Homer’s Odyssey, where it is used to translate γαστέρα, a paunch stuffed with minced meat.

Becoming Scottish

So how did haggis come to be seen as Scottish? And what does this tell us about the formation of Scottish identity?

Curiously, the first people to identify haggis as Scottish were not the Scots, but the English. There were two reasons for this. The first was a shift in patterns of consumption. By the end of the 17th century, the English diet had begun to change. As the Agricultural Revolution swept the country, productivity increased dramatically, making a wider range of better quality produce available to more people. This drastically reduced the market for offal. Though it continued to be eaten, especially in poorer sections of society, it was no longer a food of first resort – and dishes like haggis began to go out of fashion. In Scotland, however, precisely the opposite process took place. The late 17th century had been a period of economic decline. Seven years of severe famine had been followed by a devastating crash, brought on by a madcap attempt to establish a Scottish colony on the Gulf of Darién in modern Panama. There had, admittedly, been a slight recovery after the Act of Union with England (1707). But the gains were unevenly felt. While many landlords saw their incomes grow as a result of enclosure and the introduction of modern farming techniques, many poorer tenants – whose rents were increasingly set by auction – found themselves priced out of their homes by the commercialisation of agriculture. Without land or livelihood, their living conditions declined markedly. This served to increase the popularity of haggis. Since its ingredients were all inexpensive, it was something that even the poorest could afford. So, while haggis had virtually disappeared from England by the mid-18th century, it was booming in Scotland.

The second – and most important – reason was political. Not long after the Act of Union, the United Kingdom was convulsed by the Jacobite Risings, a series of attempts made by the descendents of the deposed James II to regain the throne. Though these had all been crushed, they had left an unpleasant taste in the mouth. Among the English, there was profound resentment. While they were happy enough to welcome wellborn Scots into London society and held Scottish soldiers in high esteem, they regarded most Scots – especially Highlanders – with undisguised contempt. Vitriolic attacks were published in the press and cartoons depicting Scots as godless barbarians began to appear. Food was a common focus. Given that there was thought to be a close connection between victuals and character, the perceived poverty of Scottish fare was used to deride the manhood – and even the humanity – of Scottish people. Perhaps the best-known example of this was by Samuel Johnson. In his Dictionary (1755), Johnson defined oats as: ‘A grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people.’

Haggis was a natural target. Now that it was a rare sight in England, English critics felt justified in characterising it as a specifically ‘Scottish’ dish – and in denigrating it as somehow ‘uncivilised’. In Tobais Smollet’s The Expedition of Humphry Clinker (1771), one character, travelling through Scotland, hastily reassures an English correspondent that ‘I am not yet Scotchman enough to relish their singed sheep’s-head and haggice’. And, in an earlier satire for the Briton, Smollett has ‘Lord Gothamstowe’ claim that ‘the very prospect’ of a ‘Caledonian haggis’ turned his stomach.

The Scots were not the sort to take this lying down. Their pride having been wounded, as much by the defeat of the Jacobites as by such attacks, they made a conscious effort to define themselves as ‘different’ from the English and to claim haggis as their own, with pride. The most telling expression of this was Robert Burns’ ‘Address to a Haggis’ (1786). Here, Burns implicitly acknowledged that there was a connection between food and character, but turned it to the Scots’ advantage. Other nations might have their ragout, olio, or fricassees, he argued; but that sort of food only turned a man into a weakling,

As feckless as a wither’d rash,

His spindle shank [thin legs] a guid whip-lash,

His nieve [fist] a nit [nut]

Haggis, by contrast, was the sort of food real men were made of. Those who ate it made the earth resound with their tread and could cut heads off their enemies as easily as if they were the tops of thistles. If the English wanted to sneer at it, that was their business – but they’d better watch out!

An Invented Tradition

Haggis’ burgeoning association with Scotland was consolidated in the 19th century – albeit through rapprochement rather than rivalry. Once again, it was the English who provided the spur. After so many years’ animosity between the two nations, George IV decided to try to heal the wounds by making a grant visit to Scotland in 1822. His stay in Edinburgh was choreographed by Walter Scott, who was so anxious to make Scotland attractive that he effectively invented a new ‘tradition’ of Scottishness. At the banquet thrown in the king’s honour, everyone was decked out in tartan (previously the preserve of the Highlands and Islands); and care was taken to select foods that reflected ‘Scottish’ identity – including haggis.

George IV’s visit ignited a craze for all things Scottish. Tartan became the height of fashion; a memorial to William Wallace was erected in Stirling; Robert Burns was honoured with a national festival in Ayr; Burns suppers became major events; and haggis was eaten in ever-growing quantities. Scots living abroad played the biggest role. Perhaps out of nostalgia, they were determined to make haggis the culinary centrepiece of Scottish identity. In 1845, for example, a public dinner held in the Port Phillip District of New South Wales featured tables laden with ‘orthodox Scottish feed’. Haggis was the star attraction. But Scotland itself was not far behind. By the late 19th century, haggis was widely recognised as the ‘national’ dish – and the rest, as they say, is history.

Haggis’ origins will always be controversial. As long as there are Burns suppers, there will be people arguing over whether the ‘great chieftain’ is ‘really’ Scottish. And unless some dazzlingly new evidence comes to light, I don’t expect the question will ever be settled. But in a way, I hope it never is. Haggis’ journey from mysterious beginnings to Scottish classic is as nourishing as haggis itself. Debating its origins shows us that ‘national’ dishes are always a slightly artificial construction; and that food tastes better when prejudice is left aside.

Alexander Lee is a fellow in the Centre for the Study of the Renaissance at the University of Warwick. His next book, Machiavelli: His Life and Times, will be published by Picador in March 2020.