A History of Chop Suey

Chop suey arrived with the Gold Rush, spread with the railway and endured prohibition. Although Chinese by origin, it was claimed by America.

On the night of 14 June 1904, New York’s Chinatown was plunged into a deep gloom. For the past 20 years, it had thrived off the city’s seemingly insatiable appetite for chop suey. Every night, restaurants along Moot and Pell were thronged with sophisticates clamouring for a taste of ‘authentic’ Chinese cooking. But suddenly, all that seemed at risk. A few days earlier, a chef named Lem Sen had arrived from San Francisco. Chop suey, he claimed, was ‘no more Chinese than pork and beans’. In fact, he had invented it a decade before, while working at a ‘Bohemian’ restaurant in San Francisco. His recipe had been ‘stolen’ by an American diner, who had since grown rich off the profits. Now Lem wanted compensation. Through his lawyer, he demanded that restaurants stop making chop suey – or pay him for the privilege of using his recipe.

Happily, Lem soon dropped his suit. Even he must have known it was absurd. But the myth of the dish’s ‘American’ origins persisted. Over the next few decades, newspapers regularly claimed it as Uncle Sam’s own and mocked those who were ‘gulled’ into believing that it was really Chinese. Even today, the expression ‘as American as chop suey’ can still be heard.

California Dreaming

There is little truth to any of this. But myths can be revealing. Consciously created to mask culinary realities with nativist pretentions or (in Lem Sen’s case) naive self-interest, the tales told about chop suey are a testament to the United States’ conflicted relationship with Chinese immigrants – and a witness to almost two centuries of curiosity and contempt.

Chinese people began settling in the US in the early 19th century. At first, their numbers were small, and most stayed only for short periods of time. But when gold was discovered in California in 1848, all that changed. Carried by clipper ships, word soon reached Hong Kong, Macau and Guangzhou that the pickings were so rich that it was possible to dig up as much as a kilo or more each day; and within months, hundreds of eager Chinese were flocking across the Pacific Ocean in the hope of making their fortunes.

San Francisco was their first port of call. Barely more than a village when the Gold Rush began, it was now thronged with people of every nationality – and was growing every day. Most of the new arrivals were men, with little more than a knapsack to their name. They lacked tools, clothing and, above all, provisions. It was to this need that the first wave of Chinese immigrants applied themselves. Though some headed to the gold fields, most set up as merchants, or as restaurateurs; and before long, a host of eateries festooned with yellow flags had sprung up all over town. They soon won a reputation for high-quality food and unusually low prices. An all-you-can-eat meal could cost as little as $1 – less than half the price of the meagre platters on offer elsewhere. The menus were also diverse. Though Chinese dishes were on offer, much of what they served was western in origin – and with rare exceptions, their ‘European’ customers were happy to stick to what they knew.

The Chinese population grew quickly. In 1851, around 2,700 people arrived in California; a year later, there was almost ten times that number. Inevitably, an ever growing proportion began to go into mining. But they did so in a manner of their own. When they landed in San Francisco, they were met by Chinese merchants who were contracted to supply the major mining firms with labour. They were then attached to a gang and hired out as a group. While this minimised linguistic difficulties, it also meant that they were paid less than Westerners, who tended to be employed as individuals. As a consequence, they were much in demand – so much so that, by late 1852, American miners feared they might soon be out of a job. A wave of hostility took hold. Attention often focused on the supposedly ‘bestial’ character of Chinese food. On 18 June 1853, the Weekly Alta California sneeringly claimed that the ‘Celestial’ shunned beef and bacon in favour of ‘rats, lizards … terrapins, rank and indigestible shellfish’, and ‘small deer’. A decade later, Mark Twain recalled that, visiting Mr Ah Sing’s restaurant, he and his friends had been offered ‘several small, neat sausages, of which … we suspected … each link contained the corpse of a mouse’.

Go East

Despite such prejudice, the Chinese community flourished. Migrants continued to arrive in their thousands; and, when the Gold Rush began to wind down, a growing number found work on the railways. This was a booming industry after the Civil War – and Chinese labourers were to play a particularly important role in the construction of the First Transcontinental Railroad. Working once again in gangs, they cooked their own food – and often ended up assuming responsibility for running the chuck wagons of whole sectors. Naturally, they catered predominantly to Western tastes, preparing Chinese classics only on request. But this nevertheless served to spread Chinese cuisine throughout the country. Along the tracks, Chinese-owned restaurants sprang up; and as Erica J. Peters has recently shown, many even attempted to combat ‘anti-Chinese smears’ with elaborate publicity campaigns.

Yet, the more Chinese immigrants put down roots, the greater the hostility became. Workers formed ‘anti-coolie’ leagues; the Irish demagogue Denis Kearney inflamed crowds with violent, anti-Chinese rhetoric; and, in 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed, banning all further Chinese immigration. This was just the beginning. Three years later, unemployed white miners in Rock Springs, Wyoming attacked the Chinese population, stabbing some in the street and burning others to death in their homes. Horrified, many Chinese left America for good. Others, however, moved east – to New York. And it was there that chop suey at last appeared.

Enter chop suey

As in California, many new arrivals found work as sailors, stewards, dockhands and labourers; but a sizeable minority took to selling food. There was, of course, the usual hostility. In 1883, a Chinese grocer was accused of cooking dogs and cats; and derogatory songs about Chinese cooking were sung on every street corner. But a dramatic shift had already taken place. Not only had white New Yorkers begun to frequent Chinese eateries more frequently – they had also started to eat Chinese food. Why this happened is a mystery. Most likely, it was due to diversity and poverty. More so even than California, New York was a melting pot of different nationalities – most of which lived in extreme poverty. Lacking basic cooking facilities, they frequented the cheapest restaurants they could find. More often than not, that meant Chinese.

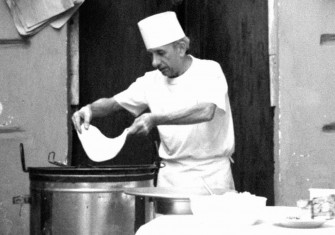

Chop suey was an early favourite. It was first mentioned by a prominent Chinese-American journalist named Wong Chin Foo in a list of common dishes he thought might appeal to Western tastes. As he explained, ‘chop soly’ could often be quite varied:

Each cook has his own recipe. The main features of it are pork, bacon, chicken, mushroom, bamboo shoots, onion, and pepper … accidental ingredients are duck, beef, perfumed turnip, salted black beans, sliced yam, peas and string beans.

Yet that it could properly be called the ‘national dish of China’ was not in any doubt.

This was, perhaps, an exaggeration; but chop suey was indeed of Chinese origin. Where exactly its roots lay has been debated; but it was probably first cooked in Taishan, in Guangdong, where most early immigrants had grown up. More properly written tsa sui (Mandarin) or tsap seui (Cantonese), its name means something akin to ‘odds and ends’.

Generally known to New Yorkers as ‘chow-chop-sui’, it soon attracted the curiosity of those further up the social scale. Though comparatively few were tempted to try it, those who did were intrigued. In 1886, the journalist Allan Forman noted that, despite its ‘mysterious nature’, it was a ‘toothsome stew’; and nine years later, the first recipe appeared in Good Housekeeping, albeit with some rather un-Chinese ingredients thrown in.

Myth-making

It was not long after this that the myth-making began. When, in 1896, the Chinese viceroy of Zhili, Li Hongzhang, visited New York, newspapers inaccurately reported that, while he had rejected Western dishes at a banquet given in his honour, he had enthusiastically tucked into a plate of chop suey. This caused a sensation. Wealthy young socialites and members of the aspirant middle classes flocked to try chop suey for themselves; recipes were published in newspapers – often with the most ridiculous ingredients. Speculation about its origins ran rife. Having never heard of it before – much less tasted it – many simply assumed that it was introduced to the US by Li Hongzhang.

This only served to fuel its popularity further. Within a matter of months, a host of new restaurants opened, especially near what is now Times Square. Known colloquially as ‘chop sueys’, these establishments adapted the recipe to suit their clientele. The more ‘exotic’ ingredients were replaced with easily identifiable meats and a few simple vegetables; and the taste was toned down so far that it became almost unrecognisably bland. The restaurants were also unusual in staying open late. Combined with cheap, ‘exotic’ food, this ensured that they became favourite haunts of theatre-goers and ‘Bohemian’ revellers. Soon, ‘chop sueys’ opened throughout the country.

Chop suey’s popularity spawned another – more bizarre – myth. Whether out of a misplaced desire to differentiate themselves from the common hoard, or because of a residual mistrust of migrants, well-to-do young sophisticates who fancied themselves as connoisseurs of Chinese cuisine began claiming that chop suey wasn’t Chinese at all – but an American hoax. In 1905, the Boston Globe tracked down six Chinese students who said they had never heard of it in China; and three years later, the Kansas City Star lamented that in none of the city’s chop sueys was ‘real Chinese cooking served’. A variety of alternative origin-stories was peddled – each more ludicrous than the last. The most common held that, at the height of the Gold Rush, a group of miners had pitched up at a San Francisco restaurant out of hours, demanding food, prompting the frightened chef to throw together whatever leftovers he had to hand to create what he dubbed ‘odds and ends’. It was nonsense; but it was soon accepted as fact.

Golden Age

Prohibition propelled chop suey to even greater heights. Unlike many Western restaurants, ‘chop sueys’ had never served alcohol – only tea; so while many of their competitors went out of business, they only increased in popularity. Their numbers grew; and, in an effort to cater to mass tastes, they began branching out. As well as an even simpler version of their eponymous dish, they offered their customers singing, dancing and in some cases opium and prostitutes.

This had a paradoxical effect. It strengthened long-ingrained prejudices. This was especially evident in films. In East is West (1930), chop suey joints were depicted as dens of unspeakable vice; while in The Detectress (1919), chop suey itself was mocked as a foul concoction of dead dragonflies, shoe leather and a puppy. But chop suey increasingly became a symbol of urbane sophistication. Louis Armstrong wrote songs about it; Miguel Covarrubias and Edward Hopper commemorated it in paintings of New York nightlife; and in Sinclair Lewis’ novel Main Street (1920), Carol Kennicott shocks the sleepy town of Gopher Prairie, Minnesota by serving it at a party.

Following the Japanese invasion of China in 1931, and the repeal of the Chinese Expulsion Act in 1943, the latter view began to prevail. As Chinese immigrants came to be seen less as a threat and more as victims, chop suey was embraced with fewer reservations. Restaurants became a common sight even in out-of-the-way towns; simplified recipes appeared in newspapers; and the first make-it-at-home kits hit the market. But the more ‘Americanised’ chop suey became, the more the Chinese themselves were pushed to the margins. By the 1950s, it was again being cast as a home-grown classic, rather than as a Chinese original; and the myths of half a century before were resurrected – albeit for rather different reasons.

The triumph of myth

Since Lyndon Johnson was roundly mocked for serving chop suey to Thailand’s Chinese-food-loving prime minister in 1968, chop suey’s popularity has experienced a steady decline. Though it is still occasionally found in restaurants and canteens, it is no longer the staple it once was; and despite the publication of some intriguing books (most notably by Andrew Coe), its past is all too often swamped by myth. This is both telling and sad. At a time when the shadow of nativism and prejudice is once again haunting the US, it would surely be salutary to revive this most ‘toothsome’ testament to Chinese immigration – and to appreciate it as such.

Alexander Lee is a fellow in the Centre for the Study of the Renaissance at the University of Warwick. His latest book is Humanism and Empire: The Imperial Ideal in Fourteenth-Century Italy (Oxford, 2018).