Seeing the Sights: Satire and Strangers

An excursion through the joys and trials of holidays past: taking in the scenery, enjoying the regional delicacies and being rude about the locals.

In the late 1700s, the vogue for sight-seeing – now a typical pursuit on Bank Holiday weekends – had arrived to stay. Even the satirists thought so:

I'll ride and write, and sketch, and print,

And thus create a real mint

I'll prose it here, I'll verse it there

And picturesque it everywhere.

Thus ran William Combe's parody of William Gilpin (1724-1804), architect of popular taste and pioneer of the idea of the Picturesque. In William Combe’s none too kindly hands, William Gilpin became Doctor Syntax, setting out on ‘Three Tours in search of the Picturesque, Consolation and a Wife’. Combe gave Syntax a horse named Grizzle, a beast with the inconvenient habit of throwing him into the nearest water whenever he stopped to see the sights.

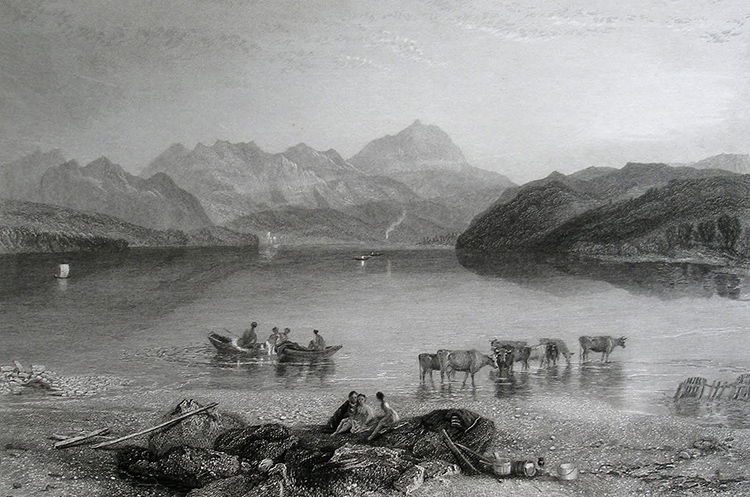

The tale of poor Doctor Syntax reminds us that tourism – especially in the upland parts of the United Kingdom – was, by then, well on the way to a permanent place in the calendar. Even the concept of the ‘season’ for tourists was making an appearance. We find it, for instance, in the journal of Nelly Weeton, who lived and worked as a governess and companion near Windermere in the early 1800s. The cult of the Romantic, the Sublime, the Picturesque was at its peak: Wordsworth was Weeton’s near neighbour; and, like the swallows, visitors were beginning to arrive in the Lake District every spring. ‘The season is now commencing for visits to the lakes,’ Weeton recorded in May 1810. She noted that in addition to the scenery, one S.T.Coleridge was also ‘worth observation’.

Yet it was not long since destinations like the Lake District had been viewed with horror. Keith Thomas’ study ‘Man and the Natural World’ demonstrates how, in the 1600s, mountains were viewed as ‘warts’ and ‘deformities’. And, even in 1769, the poet Thomas Gray is said to have found the sight of Skiddaw so disturbing that he shut the blinds of his carriage to keep the vista of untamed nature at bay.

As for that intrepid traveller, Celia Fiennes (1662-1741), it seems that the further into the north west of England she travelled, the less she liked it – and the prospect of crossing the border into Scotland seemed almost to finish her completely.

Putting Windermere behind her, Fiennes headed over the Kirkstone Pass for Ullswater and Penrith, through ‘inaccessible high rocky barren hills’ and ‘villages of sad little huts’, which she mistook at first for cattle sheds. In Carlisle, she noted cathedral and adjacent streets approvingly, but balked at the price of accommodation. Charged 12 shillings for two joints of mutton, a pint of wine, bread and beer, ‘it was the dearest lodging I met with’, she confided to her journal.

But worse was to follow. Venturing ever so slightly north of Gretna into Scotland, Fiennes came upon a house in which she could not bring herself even to sit down. Almost everything was to complain about: the Scots were slothful, they were deficient in chimneys and bridges, their miles were too long and there was no wheaten bread to be had.

For the most part, she was told, ‘persons that travel’ in Scotland went from one nobleman’s house to another. And even then, there were problems. ‘Those houses are all kind of castles and they live great, though in so nasty a way ... one has little stomach to eat or use anything.’

A tourist’s dilemma indeed. Happily, to a seasoned traveller like Celia Fiennes, the solution was obvious. She quaffed in all innocence the ‘exceeding good Claret’ from France – the ‘truest French wine I have drank this seven year’ – and ‘Whisky Galore’, surely a beverage with a back-story; paid for the ‘good dish’ of salmon and amber-coloured trout with which her landlady presented her; and, spurning, the unpalatable Scots oatcake altogether, departed with her fish for a more civilised kitchen. That kitchen was to be found in England, back over the rivers Sark and Esk.

Nearly 150 years later, Miss Weeton covered some of the same ground that Celia Fiennes had travelled. This time, the place was busier and more civilised than in Fiennes’ day. Weeton, for instance, made one of a party wending its way up Fairfield, the highest of the Lake District fells, the men on foot, the ladies in a cart, until the point at which they had to disembark and make the last stretch of the journey on foot. At the summit they refreshed themselves with a ‘hearty meal’ of veal, ham, chicken, gooseberry pies, rum, brandy and bitters that had gone up the mountain with them and admired the sea view spread before them through the ‘prospect glasses’ which they had somehow also squeezed into their baggage. ‘I was much pleased, though awed by the tremendous rocks and precipices in various directions,’ Weeton recorded.

It is interesting too, to see how the local population met the demands of these ‘strangers.’ In the pages of Celia Fiennes, it seems nothing out of the ordinary for a traveller of Fiennes’ quality to impose herself on the inhabitants of a ‘poor cottage’ for the night. But what her landlady made of Fiennes using the best sheets in the house to protect her own linen from ‘dirty blankets’ is not something we find out.

By Nelly Weeton’s time, the impact of a burgeoning hospitality trade begins to be noticeable. Thirty years earlier, Weeton noted, a passing stranger would have automatically been offered the best bed and food, without expectation of return – the sort of ad hoc arrangement Fiennes had experienced. Now, however, all was changed. ‘Wealth has flowed into the country,’ Weeton explained, and where there had been ‘genuine’ hospitality, there was now ‘avarice and rapacity’.

But, regardless of the date, seeing the sights could prove wearisome. ‘The more I travelled northward the longer I found the miles,’ Celia Fiennes remarked. Or, in words with resonance for any parent – ‘Are we nearly there yet?’

Sarah J.P. McNeill is a historian and writer.