Inside the Ancient Bull Cult

King Minos and the Minotaur remain shrouded in mystery and mythology, yet evidence of a Bronze Age ‘Bull Cult’ at the Minoan palaces abounds. Were bulls merely for entertainment or did they have a deeper significance?

Detail from the Bull-leaping fresco from the Minoan Palace of Knossos. Carole Raddato (CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED).

It was Greek mythology, as represented in the works of Homer and Apollodorus, that first prompted antiquarians to search for the fabled island civilization of King Minos, the backcloth against which the struggle of the hero Theseus with the Minotaur was supposedly enacted. Interest in locating ‘Homeric’ sites of the pre-Classical Greek world was stimulated in 1870, when the pioneering archaeologist, Heinrich Schliemann, claimed to have identified the city of Troy.

His later excavations at Mycenae, in the Argolid region of mainland Greece, soon revealed further spectacular evidence of an ‘age of heroes’, including the so-called ‘gold mask of Agamemnon’. By 1876, Schliemann was convinced that the epic poems of Homer were, in fact, reliable historical documents; and when he turned his attention towards Crete, more sensational revelations were expected, this time of the lost civilization of King Minos. Schliemann, however, was unable to obtain permission to excavate; and it was not until 1899 that the site of Knossos was explored, under the direction of Sir Arthur Evans.

Like his predecessor, Evans was aware of the mythology of Crete and the ancient travel accounts of Pausanias; but he was primarily drawn to the island by his ambition to establish the origins of the Greek language. His excavations produced the curious Linear B tablets, which defied decipherment until 1952, when the outstanding researches of Michael Ventris and John Chadwick proved that the ancient Cretan script was the forerunner of Archaic Greek.

The tablets had defeated Evans; but he was left with the triumph of having unearthed the vast royal complex at Knossos, parts of which he ‘restored’ in controversial fashion. Evans was certain that he had discovered the royal seat of King Minos; he labelled the entire Bronze Age civilization of the island ‘Minoan’, after the mythical king. The account of the excavations at Knossos, published between 1922 and 1935, bore the grandiose title The Palace of Minos.

As in the case of Schliemann’s discovery of what he had believed to be the Homeric city of Troy, much of the romance that surrounded the findings at Knossos has now been dispelled. King Minos and the Minotaur remain shrouded in mystery and mythology; yet Evans’ consummate achievement was the exposition of the remnants of a culture in which the image of the bull held portentous significance.

Cretan painters, sculptors and metal-workers have bequeathed to posterity a wealth of scenes and artefacts which show that the bull and the associated ‘bull-sports’ played a prominent part in the lives of the Bronze Age inhabitants of the island. The precise meaning of the bull-image has provoked a good deal of speculation throughout this century, as the continuing process of excavation has increased our knowledge of Minoan culture.

Many ancient peoples respected the bull as a symbol of strength and fertility; its size, power and potency have impressed man for many thousands of years. Bronze Age Crete, however, constitutes something of a special case; it has produced not only static representations of the bull itself, but also the highly mobile figures of the bull-leapers, young people of both sexes, apparently performing astounding acrobatical feats using a charging bull in much the same way as modern-day gymnasts might use a piece of fixed apparatus.

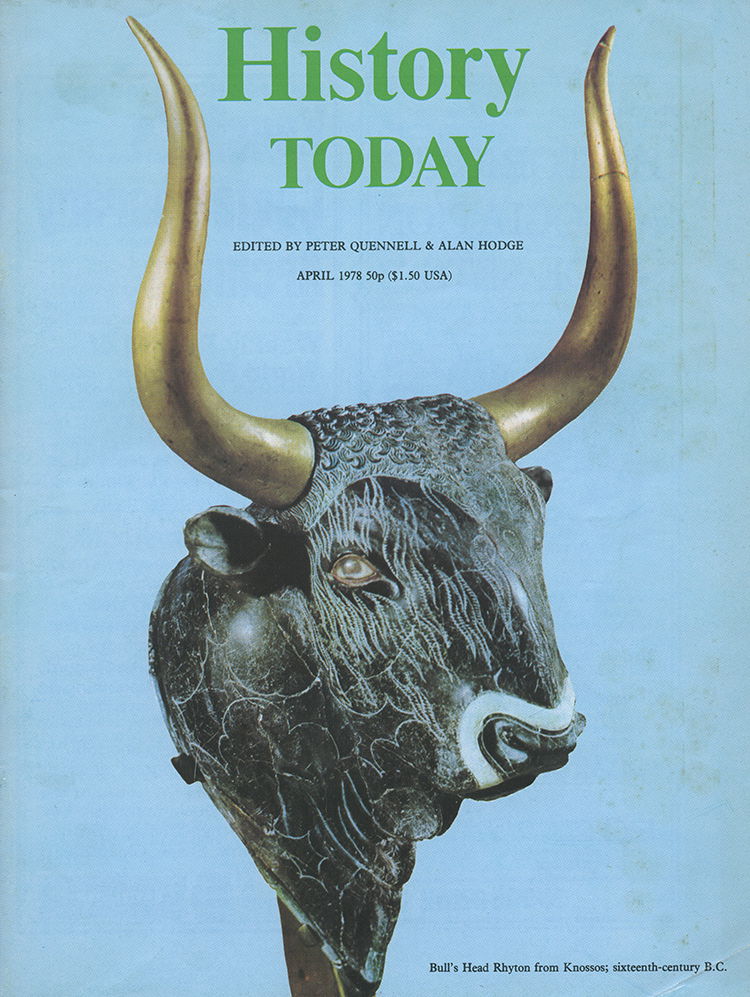

The palace at Knossos yielded the famous ‘bull-leap’ fresco painting; seals and signets found at several sites bear the bull’s horns motif; the image of the bull appeared on funerary furniture, and in the form of rhytons (pouring vessels).‘Bull-leapers’ were depicted in a variety of activities, and were fashioned from a wide range of materials, including bronze, ivory and terracotta.

At first it was thought that the ‘bull-cult’ had been confined to the royal precincts at Knossos; but examination of the palaces at Phaistos and Malia, the ‘summer palace’ at Hagia Triada and other important sites at Zakro, Armenoi and Pseira, has provided evidence that the phenomenon was fairly widespread throughout the island.

As has been noted, the bull had fascinated man both before and after the Aegean Bronze Age. Palaeolithic cave paintings from Lascaux in France, which depict the strength and ferocity of the bison, have been dated to c.13,500 BC by radiocarbon analysis. The civilizations that flourished in Anatolia and Mesopotamia between 6000 BC and 2000 BC have furnished us with many striking examples of the bull-image, from the vivid murals at Catal Huyuk to the intricate and delicately-made golden head of a bull from the city of Ur.

The theme of the bull persisted in Near Eastern artwork for centuries, culminating in the monumental winged bulls of the Neo-Assyrian age. There has been considerable speculation as to the possible magico-religious significance of such objects. The Ancient Egyptians observed the religious cult of Apis, the Bull of Memphis, and also revered Mnevis, a minor deity who took the form of a huge, heavily built black bull. Long after the waning of the Aegean Bronze Age, the Etruscan peoples of Italy decorated their funerary furniture with bull-scenes, in much the same way as the Cretans had done.

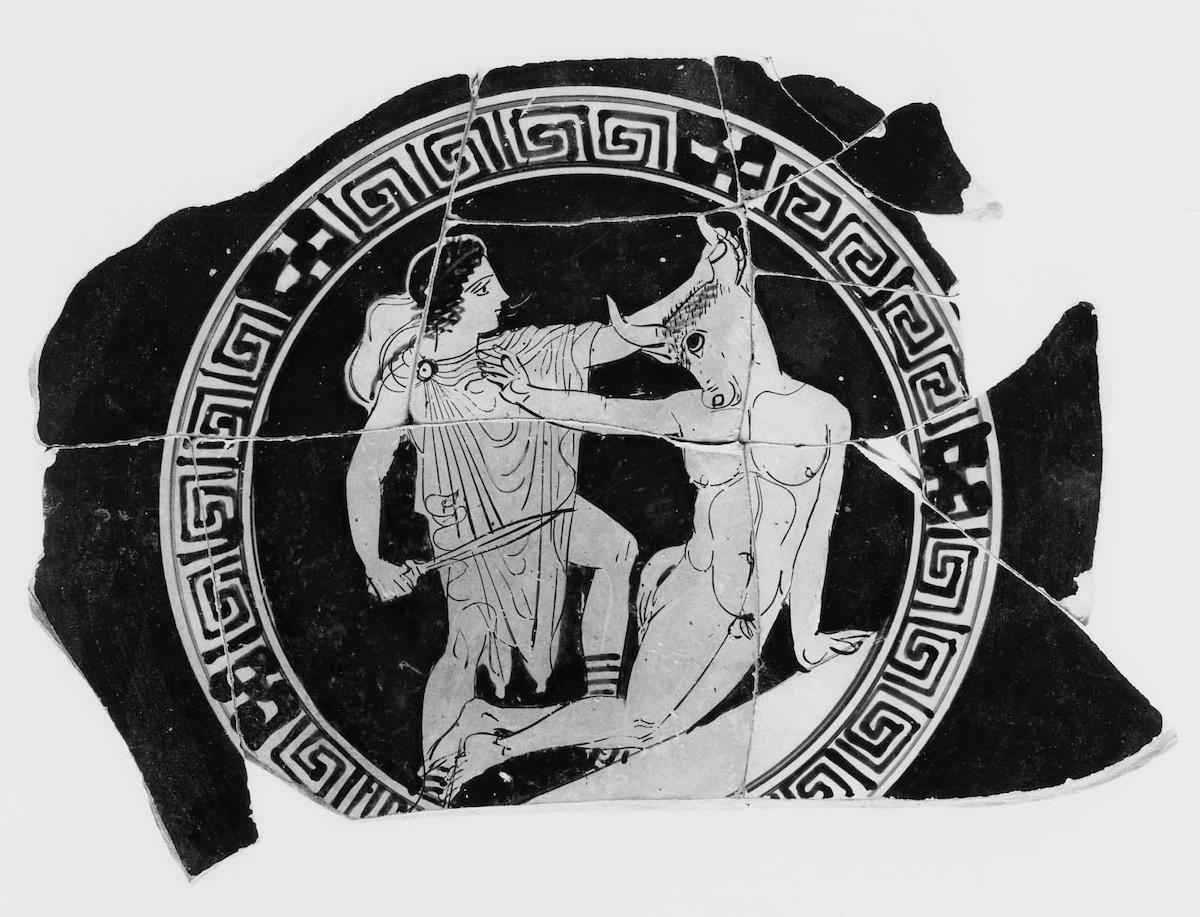

Greek vase-painters of the sixth century BC tended to depict some of the more outlandish mythological scenes; yet the theme of Theseus and the Minotaur was not neglected, as the black-figure ‘Francois vase’ and the red-figure work of the ‘Panaitos painter’ show. The bull continued to have significance well into the age of Rome; Cato gives an account of the rustic ceremony of the lustratio, the cleansing and purification of the land, in which a sacrificial bull is led around the field concerned, before its blood is scattered over the ground.

The wealth of bull-images found in Crete encouraged archaeologists to re-appraise some of the similar items found elsewhere. In particular, attention focused on two gold cups, called ‘Mycenaean’, discovered at Vapheio, near Sparta, some 20 years before the excavations at Knossos. These richly-wrought vessels, in the so-called ‘tea-cup’ style, depicted scenes very similar to some of those found in Crete, especially a rhyton from Hagia Triada. The first Vapheio Cup relief shows what is apparently a bull tethered by its hind leg, with a second bull recumbent nearby; but the ‘second bull’ is, in fact, a cow, probably used as a decoy to attract the bull, who was then smartly roped by concealed captors.

The head of the bull is raised, its expression one of anger. The second cup depicts hunters, in the typically Cretan slim-waisted style, attempting to ensnare a bull by suspending a net between two trees. The bull is seen, on the next relief, to be apparently firmly enmeshed; but the final scene reveals that the bull has broken free and trampled one of his would-be captors, while a second, thought to be a girl, seemingly wraps herself around the bull’s horns. The theme, the figures and the style of workmanship are all typically Cretan, despite their location at Vapheio; the cups were probably imported from Crete, or produced on the Greek mainland by Cretan goldsmiths.

The not-so-gentle art of bull-catching is similarly portrayed on one of the reliefs of the Hagia Triada rhyton from southern Crete; a young man is shown near a bull, but not engaged in any form of athletic activity. He is about to attempt to capture the bull. And a painting on a crystal plaque from Knossos shows a rope being used to capture a bull; the resemblance to the subject matter of the Vapheio Cups is inescapable.

By far the most controversial of the finds from Knossos was the famous ‘bull-leap’ fresco painting. Executed around 1500 BC, the scene was discovered in a small enclosure in the eastern wing of the royal palace, and is thought to have once been part of a frieze. A huge bull charges forwards, a bronzed male seemingly performing a somersault along its back, while two attendants or fellow participants, painted in light colours to denote females, wait to catch or steady the performer. Sir Arthur Evans had no doubts about the interpretation of this amazing scene:

the girl acrobat in front seizes the horns of the coursing bull at full gallop, one of which seems to run under her left armpit. The object of her grip clearly seems to be to gain a purchase for a backward somersault over the animal’s back, such as is being performed by the boy. The second female performer, behind, stretches out both her arms as if to catch the flying figure, or at least to steady him when he comes to earth the right way up.

Given our understanding of gymnastics, such a feat as that outlined by Evans seems highly improbable. Many authorities, including Sir Denys Page and Professor John Chadwick, have argued that it would have been physically impossible for even the most highly trained athlete to have performed a backward somersault along the back of a bull charging at full tilt, much less to be caught by an assistant.

American ‘steer-wrestlers’, with first-hand experience of a similar kind of sport, have insisted that it would have been impossible to have grasped the horns of the bull in the first place, as the force of the charge – three times that of a ‘steer’ – would have thrown anyone standing in front of, or alongside, the bull off balance; and the danger of being seriously gored is self-evident.

Art historians have claimed that the scene can be explained in terms of the failure of the artist to show perspective; and this would account for the seemingly impossible positions of the participants. Yet other bull-leaping scenes are to be found on seals and signets depicting a variety of acrobatic skills; sometimes the performer lands on the back of the bull hands-first, sometimes feet-first. Such scenes cannot have been entirely the figment of the artist’s imagination.

The object of the exercise may have been for the performer to excite the bull to charge, and then to leap forwards, high in the air, at the crucial moment, tucking up the legs so as to allow the bull to pass underneath without contact being made. This manoeuvre may well have succeeded, provided that the bull was not charging at a great pace. Alternatively, acrobats could have performed somersaults and handstands across the back of the bull rather than along it, while the animal was still, or by approaching it from an angle outside its field of vision. One seal does show a sideways leap being performed across a recumbent bull.

Even so, the risk of death or serious injury must have been appallingly high. We may never know the exact nature of the leaps performed since, as has been wryly observed, few of the world’s top-class athletes seem willing to put the theories to the practical test. Because of the obvious dangers of bull-leaping, the question has invariably arisen, were the performers participating of their own free will, or were they forced to do so? Were the ‘bull-sports’ a refined form of human sacrifice?

A study of Greek mythology provided interesting insight into the matter; but the question cannot be answered on the basis of the archaeological evidence. It would seem unlikely that the Cretans practised human sacrifice to the bull, since they did not worship it as a major deity. Similarly, the question of the willing participation of the bull-leapers is one that cannot be answered; it remains a topic for speculation.

The bull-leapers are invariably shown to be young, slim, supple and well-proportioned, both boys and girls. They are clad in a loincloth, wear decorative bracelets, armlets and ankle-gaiters; they are long-haired, the hair usually curled. There was nothing particularly remarkable in the participation of women in the bull-cult; a society that frequently depicted women as ‘goddesses’ in varying shapes would have seen nothing unusual in this. The bull-leapers are unarmed; their activity did not correspond to a bullfight, but more to an exibition of athletic prowess.

There is little clear information on the subject of the location of the bull-leaping spectacles. Crete has yielded nothing in the way of bull-rings or amphitheatres as we know them. It has been suggested that, at Knossos, the area between the river and the state-rooms would have been a convenient situation for the staging of such events; but they could have been equally well accommodated in the large central courtyard of the palace itself.

Examination of the plans of other palaces, notably those at Phaistos and Malia, reveals a similar form of construction, and therefore provides no conclusive solution to the problem. Traditionally, it was thought that the bull-leaping would have been performed for the benefit of members of the royal court only; but modern opinion believes that the event would have taken place in public. But were the bull-sports merely for entertainment, or did they have a deeper significance?

There is a scene from a painted limestone sarcophagus from Hagia Triada showing a bull trussed up on a sacrificial table, while a priestess offers libation at an altar; it follows from this that the bull would hardly have been seen as a sacrificial animal, had it been a major deity in its own right. The people of Crete, like those of many other ancient societies, recognised the bull as a symbol of strength, and probably believed that bull’s blood had certain magical properties. Recent work on the Linear B tablets argues that the Cretans worshipped prototypes of some of the Classical Greek deities.

They also appear to have worshipped the mother goddess in a variety of forms; although the island is devoid of temples and monumental votive sculpture, there are many miniature likenesses of woman, the goddess of nature, usually shown in the company of her ‘subjects’, the snake, the dove and the bull. It is thought that the mother goddess was a nature goddess, the goddess of animals, the guardian of earth, sea and the harvest.

That the bull should occupy a prominent place in such a society was quite natural; its power and potency constituted an important adjunct to the aura of the mother goddess. The bull-leapers are invariably shown to be young and beautiful; the bull is usually shown to be ferocious and powerful. The bull-leap could be seen to combine the elements, almost, of ‘beauty and the beast’, which may well have held some form of magico-religious significance for the Cretans. Murals illustrate that the mother goddess looked down on the bull-sports, another factor which argues that the spectacle had some form of religious symbolism.

The bull’s head rhyton from Knossos may have been used as a libation vessel in religious ceremonies. Made from steatite, it was an exceptionally intricate piece; the eyes, of painted rock crystal produce a shimmering effect; and the muzzle is a fine example of shell-working. Such a vessel would have been far too elaborate for simple, everyday usage as a drinking vessel. The site of Pseira in eastern Crete has also yielded some unusual rhytons in terracotta, made from a mould, the size of which suggests that they may have been votive objects as well as pourers. They take the form of a bull in static, standing pose.

Sir Arthur Evans believed that the bull had an even greater significance to the ancient Cretans than has been shown. In the basement of a small house at Knossos he found the skeletal heads of two bulls, ‘the horn-cores of one of which were over a foot in girth at the base’. Taking a line from Book XX of The Iliad (‘In bulls does the Earth-Shaker delight’), Evans reasoned that there must have been a connection between the roar of a bull and the rumbling of an earth tremor, to which Bronze Age Crete was frequently subject.

He himself claimed to have experienced tremors in which ‘a dull sound arose from the ground, like the muffled roar of an angry bull’. Perhaps romance was beginning to gain the upper hand on reason. Yet was there not a slight possibility that the Cretans might have experienced similar sensations? It is hardly a scientific explanation of the importance of the bull-cult in itself. But remembering the reverence with which ancient rural societies treated the bull as a symbol of power and fertility, and given the seismographic fluctuations on the Aegean, dare we dismiss the idea altogether?

This article originally appeared in the April 1978 issue of History Today.