Did Sauropods Walk or Waddle?

Sauropod dinosaurs were the largest land animals ever to have lived – but how did they live?

Four feet long and made of plaster, a lifelike model of Diplodocus carnegii lurks atop one of the cabinets in the Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences in Cambridge. But the countless millions who have seen ‘Dippy’ the dinosaur – whether the original fossils at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, the cast formerly on display at London’s Natural History Museum, or one of many other casts worldwide – will notice that something is off. Diplodocus usually stands to attention with straight, elephantine legs, but the limbs on this model bend out to the sides, almost in the manner of a crocodile.

The Cambridge model was cast from a plasticine original in 1916 by the science journalist Henry Neville Hutchinson. He wished to register his belief that the diplodocus in London – and, by extension, everywhere else – had been incorrectly reassembled. Hutchinson believed that this sluggish reptile had waddled, not stridden, through life. His concerns spoke to a widespread sense of quasi-incredulous fascination with the long-necked sauropod dinosaurs. They were the largest land animals ever to have lived – but how could such animals have lived? With tiny brains, feeble teeth, and unimaginable bulk, they appeared utterly unfit for survival. Hutchinson and his contemporaries strained to imagine why such disproportionate animals had even evolved in the first place.

Answering these mysteries was important, because dinosaurs like Dippy had become fossil celebrities. If Hutchinson was right, then the Natural History Museum had made a very expensive mistake.

Sizing the dinosaurs

In the 1820s the earliest researchers of the extinct reptiles later called dinosaurs – then known from the South of England – had only isolated fossils to work with. They made sense of these through judicious use of analogy. Comparing monumental but incomplete fossil remains from Sussex with the bones of modern reptiles, for instance, naturalist Gideon Mantell suggested that his iguanodon was a saurian colossus as much as 100 feet long.

Further research deflated these estimates considerably, but they came to seem less incongruous when dinosaurs were unearthed in the US. After the Civil War ended in 1865, the US’ westward expansion continued apace: Native American peoples were hounded into reservations and new states added to the Union, while the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 made navigating these absorbed territories easier for prospectors, tourists, settlers – and palaeontologists. In 1877 men on the ground in Colorado and Wyoming sent word that gigantic dinosaur bones were there for the taking – if money for excavation was forthcoming.

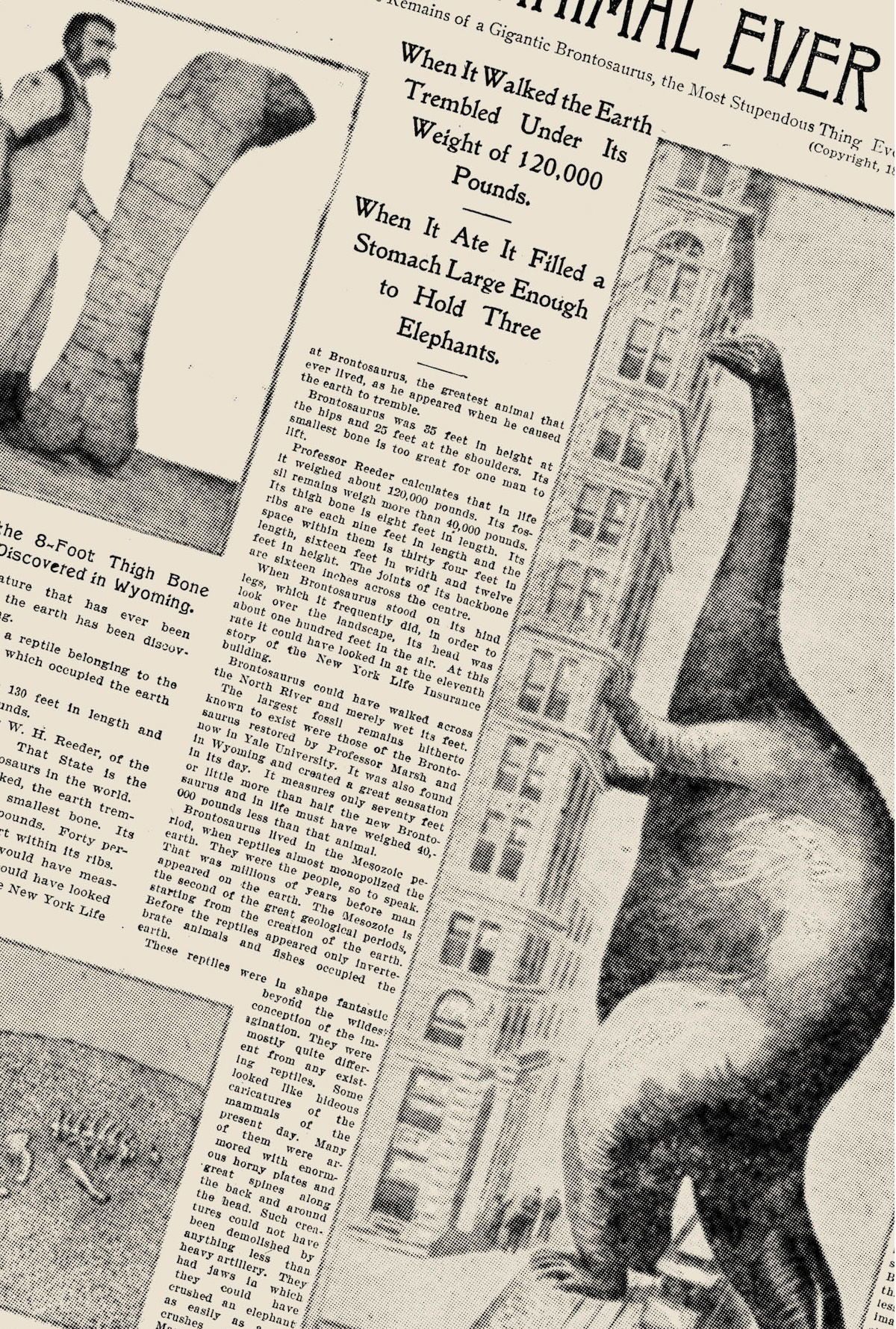

Two palaeontologists, O.C. Marsh of Yale College and his Philadelphia-based rival E.D. Cope, raced to acquire and classify as many of these bones as possible. In just three years, between 1877 and 1879, they named memorable genera such as diplodocus, brontosaurus, camarasaurus, and atlantosaurus. The sizes approached Mantell’s most sanguine estimates regarding iguanodon. Marsh told the American Journal of Science that, if Atlantosaurus montanus ‘had the proportions of a crocodile, it was at least eighty feet long’. He gave these prepossessing dinosaurs the bizarrely unprepossessing name sauropoda (‘lizard foot’).

Aware that palaeontology’s pace quickly rendered old interpretations obsolete, Cope and Marsh made only limited attempts to imagine how sauropods had looked and lived. They mounted no complete skeletons for display. When an atlantosaurus femur arrived in London in the mid-1880s it stood alone, like an evocative fragment of Grecian statuary. For the novelist Grant Allen, it evoked images of ‘unwieldy monsters hopping casually about’. The doyenne of occultism Helena Petrovna Blavatsky responded with her usual idiosyncrasy. Noting that the femur alone was ‘over six feet in length’, she concluded that, since dinosaurs were so large, prehistoric humans, too, must have been giants.

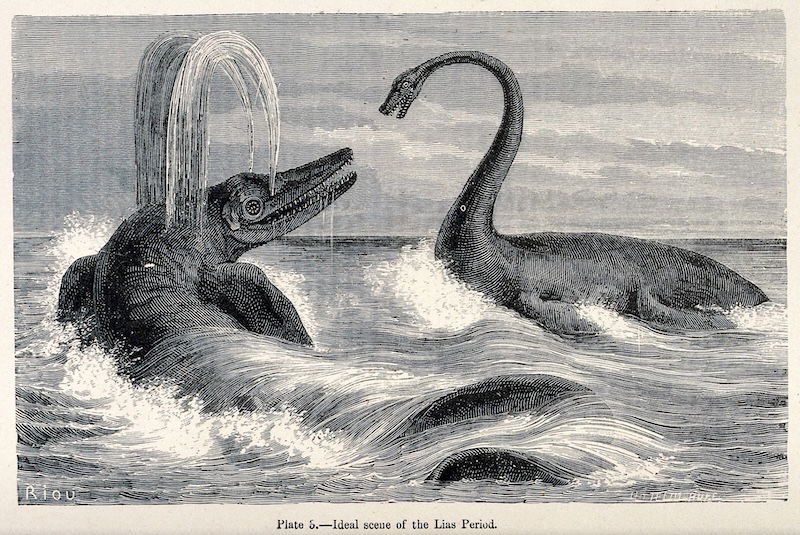

Hutchinson offered a more grounded response to the American specimens. The vivid illustrations by Joseph Smit in Hutchinson’s popular book Extinct Monsters (1892) would have been most readers’ first sighting of sauropod dinosaurs. Smit sketched two brontosaurs, one on land and one submerged, handily illustrating Marsh’s offhand suggestion that these animals were ‘more or less amphibious’.

Writing in the age of evolution, Hutchinson was also intrigued by something that had not been part of dinosaur palaeontology in earlier decades: the notion that dinosaurs, however formidable they appeared, had been inadaptive failures. The gigantic sauropods seemed the apex of this paradox. Whatever its sublimity of scale, brontosaurus, a ‘stupid, slow-moving reptile’ lacking ‘offensive weapons of any kind’, hardly appeared a product of the survival of the fittest. That such inadequate animals had gone extinct, leaving no ancestors, made sense.

Crocodile stance

At the century’s close, sauropods became profitable objects of philanthropy. Men such as Scottish-American industrialist Andrew Carnegie realised that funding the excavation and display of these imposing skeletons cast the accumulation of outlandish wealth in a flattering light. The plaster diplodocus he commissioned was unveiled at the Natural History Museum in 1905; the original bones were mounted in Pittsburgh, where Carnegie had made his fortune, two years later. Other casts went to Berlin, Paris, Bologna, St Petersburg, and more. Sauropods were becoming indispensable exhibits for any world-class natural history museum.

As the public flocked to these displays, the era’s most talented palaeo-artists, including Charles R. Knight in the US and Alice B. Woodward in Britain, put flesh on the bones. Their paintings and drawings experimented with imagined postures and habits: lumbering on land, drowsing in swamps, and even – although not often – rearing on hind legs to seek food.

Following the precedent set by Cope and Marsh’s publications, and by the newly mounted skeletons, Knight and Woodward depicted sauropod limbs as held straight under the body, like the limbs of mammals. But this became controversial. After Dippy’s installation in London, scientists attuned to the mechanics of modern reptiles proposed that only the splayed stance of a crocodile would have made sauropod life bearable. In part, this was because most people assumed sauropods were algae-guzzling animals that lived around swamps, and perhaps even relied on water to hold up their bulk. In 1908 the American naturalist Oliver Perry Hay pointed out that, had sauropods’ load-bearing legs concentrated their weight underneath the body, these animals would have sunk and ‘perished miserably’ in mud.

From 1909 the Berlin zoologist Gustav Tornier emerged as the chief German proponent of the crocodile stance for sauropods. Aspects of this debate were nationalistic, especially as the media latched on: Tornier hinted that publicity-hungry Americans had prioritised spectacular height over solid anatomy. But it wasn’t all nationalism. E. Ray Lankester, who had been director of the Natural History Museum when Dippy was installed, later admitted that ‘on land he would have rested on his belly, as a crocodile does, with much bent legs on each side’.

Senseless sauropods

Conveniently for the museums bearing diplodocus displays, the controversy over stance had mostly fizzled out by the 1920s. Few now argued that these animals needed to be expensively remounted to remove their mammalian posture. In every other way, however, sauropods still represented the opposite of mammals. After the Mesozoic Era, mammals had taken over the world with their vigour, adaptability, and intelligence. In contrast, sauropods represented reptilian impracticality incarnate. Many palaeontologists saw them as victims of inexorable forces: once the trend towards size began, a kind of evolutionary momentum carried it beyond the point of utility for survival in anything other than the gentlest environments.

This self-defeating size, combined with negligible intelligence, made sauropods into targets of scorn. In a newspaper column of 1925 the Natural History Museum’s keeper of geology F.A. Bather suggested that brachiosaurus – a sauropod excavated by the Germans in colonial East Africa – could have lived on even ‘with the brain bitten out’, its heart continuing to beat ‘until bit by bit the living but senseless flesh’ was devoured by predators. This was an animal of mechanical instinct, Bather said, ‘devoid of all such sense as would give it craft or courage, pleasure or pain’.

For decades, only occasional dissenting voices broke through this disdain. From the late 1960s, however, something changed. Amid a wider analysis of the evolution, metabolism, behaviour, and intelligence of dinosaurs, spearheaded by US palaeontologists such as Robert Bakker, sauropods were transformed. Palaeontologists now attributed efficiency and adaptability to animals formerly seen as evolutionary mistakes. Cinema brought these reinvigorated animals to life. In a virtuosic rebuttal of most of the century’s sauropod science, the first showpiece of CGI in Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park (1993) depicted a terrestrial brachiosaurus nimbly launching onto its hind legs. No longer a lethargic swamp-dweller, this sauropod was an object of awe and respect – and once again the product of an astronomical investment of funds.

Richard Fallon is Research Associate in Natural History Humanities at the University of Cambridge.