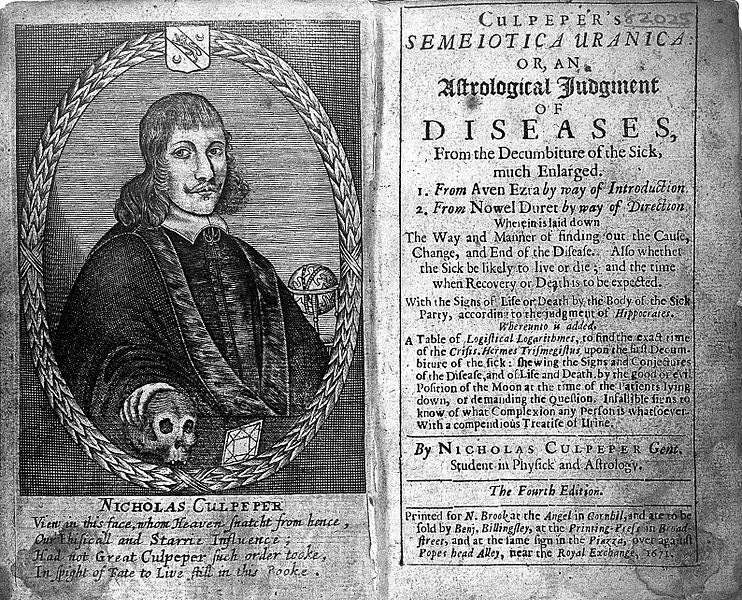

The English Physician

Despite his Complete Herbal being one of the most enduring medical texts, Nicholas Culpeper was firmly outside the establishment of the medical world.

October 18th, 1616 saw the birth of the botanist, herbalist, physician and astronomer Nicholas Culpeper and, while he is best known for his book The English Physitian, better known as Culpeper’s Complete Herbal, the dramatic and often painful elements of his life are less familiar.

October 18th, 1616 saw the birth of the botanist, herbalist, physician and astronomer Nicholas Culpeper and, while he is best known for his book The English Physitian, better known as Culpeper’s Complete Herbal, the dramatic and often painful elements of his life are less familiar.

One reason is that any ‘facts’ we know about him derive mainly from a 15-page biography published after his death by William Ryves, the veracity of which is open to question. And, over the intervening centuries, belief in astronomy went out of fashion and Culpeper fell from favour.

Just 19 days before Culpeper's birth, his father died. The affluent Culpepers (Catherine Howard was of Culpeper stock) offered Mary, Nicholas’ mother, no help, obliging her to return with the baby to her father’s house in Sussex.

The Reverend William Attersoll, rector of St Margaret’s Church in the village of Isfield, was already a dissatisfied man and the arrival of his daughter and the child was a further irritation. He described children as ‘the miserablist and silliest creatures that can be devised’, but he nevertheless saw it as his duty to provide instruction for his grandson. William Attersoll was a Puritan who had written several books of Biblical analysis. As well as instruction in scripture, classics and mathematics, he instilled in Culpeper a strong disrespect of the Crown. It was also from Attersoll, who was familiar with Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos, that Culpeper inherited his interest in astronomy.

Other formative influences in Culpeper’s life at that time were the Sussex fields and woods, where he familiarised himself with the plants with medicinal properties, known to herbalists as ‘simples’, which he found growing locally and then, in the company of his mother and other women, learnt their ‘virtues’, or uses.

At the age of 16 he went up to Cambridge, ostensibly to study theology, but he preferred to read Galen and Hippocrates and attend lectures on anatomy. Like many students, he spent time smoking and drinking in taverns. At this point, if Ryves' Life is to be believed, his youth was blighted by a romantic tragedy. He had met and fallen in love with ‘A Beautiful Lady’, whose father was one of the ‘noblest and wealthiest men in Sussex’. Judith, the daughter of Sir John Shurley, Baronet of Isfield, seems the most likely candidate as she and Nicholas had been childhood companions. They were apparently preparing to elope when, on the way to the tryst, her carriage was struck by lightning and she was killed. Although there is no record of this among coroners’ reports (and some claim it as astrological symbolism) it is at this point that Nicholas left Cambridge, ‘burdened by deep melancholy’ and went to London to begin a seven-year apprenticeship to Simon White, apothecary of Temple Bar.

There were strict divisions between what university-educated physicians and apothecaries could do, and for Nicholas this was a come-down. Then, to make matters worse, the business failed and White ran off to Ireland with the apprenticeship money. Homeless and penniless, Nicholas was lucky to find a new master, Francis Drake, who, instead of charging him, asked for Latin lessons in exchange. As part of his training he was taken on plant-hunting expeditions by Thomas Johnson, editor of the newly enlarged Gerard’s Herball, and things seemed to be going well. But, two years later, Francis Drake died and Nicholas found himself again ‘turned over’, this time to an unpleasant elderly apothecary. Shortly afterwards he dropped out.

Although unqualified, he decided to set up his own astrological-medical practice. He chose St Mary Spital, beyond the city walls and outside the jurisdiction of both the College of Physicians and the Society of Apothecaries.

At the age of 24 he fell in love again, this time to a 15-year old heiress, Alice, whom he had met when treating her father for gout. His good fortune, however, was not to last. Shortly after his marriage he fought a duel – it is not clear why – and he not only had to pay his opponent’s medical expenses but also to flee to France.

Upon his return, a serious accusation was made against him by a patient – witchcraft – and he was imprisoned. The groundless accusation was given weight because of Nicholas’s belief in the influence of the celestial bodies on the wellbeing of patients. This, with its associations of ‘magic’, counted against him but, when he was brought before a jury, he was acquitted.

As early as 1641 Nicholas had observed people drilling in the Artillery Ground at Spitalfields and it is not surprising that, as an anti-royalist, when the Civil War broke out he enlisted as a field surgeon with the Parliamentarians. On the way to the battlefield he collected medicinal herbs but before long he was in the thick of the brutal fighting and was shot in the chest and badly wounded. As a heavy smoker and possibly already suffering from consumption, this was to shorten his life.

He continued to treat poor patients cheaply, earning not only great local popularity but also the bitter condemnation of the medical fraternity, whose ire knew no bounds when, in 1649, he produced an English translation of their bible, the Pharmacopoeia Londoninensis. While this contained the recipes for their remedies, Nicholas’s translation, A Physical Directory, also set out the common names of the ‘simples’ and how to administer them; he also added valuable material of his own. Another important book was his Directory for Midwives, an unusual topic for a male herbalist, which may have been inspired by painful experience; for, although Alice bore him seven children, only one daughter lived to adulthood.

Nicholas Culpeper died at the age of 39 having written numerous influential works – his Herbal was among the books taken to by pilgrims to the New World. Perhaps his lasting legacy was to demystify medicine and place help in the hands of the people themselves.

Patricia Cleveland-Peck is a freelance garden writer who contributes to Hortus, The English Garden and BBC radio.