Fifty years of the Journal of Contemporary History

Few publications have done more for the cause of contemporary history than the JCH.

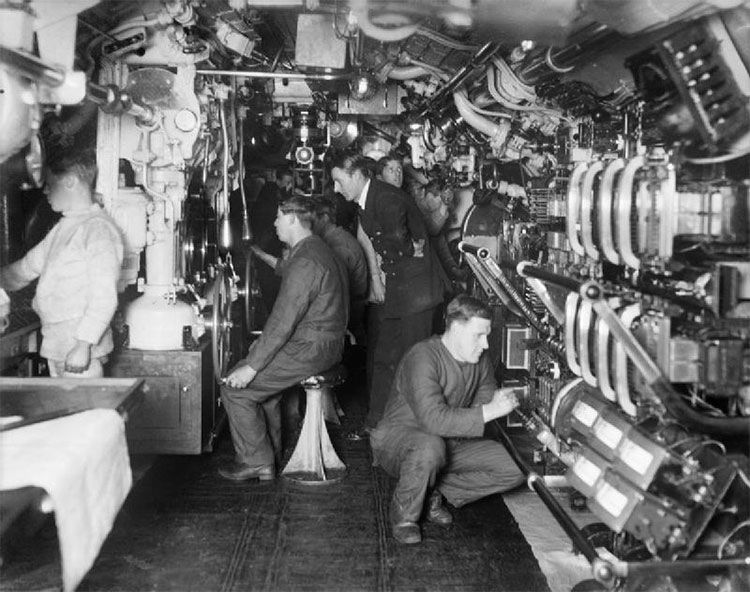

'The Ministry of Defence does not comment on submarine operations.’ This stonewalling sentence is delivered with steely calm to anyone who seeks to garner information on the Royal Naval Submarine Service (RNSS), the ‘special breed’ of men (soon to be joined by women) who dive into the depths aboard Britain’s nuclear submarines. The sheer difficulty of getting any information out of the MoD on this subject makes The Silent Deep, the new history of the RNSS by Peter Hennessy and his research assistant, James Jinks, all the more remarkable. Over 800 or so pages, they have managed to reveal to the world, using copious documents and the testimonies of submariners themselves, to tell a tale that, in its frankness, has surprised even Royal Navy veterans. It is a testimony to the skill – and charm – of Hennessy, perhaps Britain’s most famous contemporary historian.

'The Ministry of Defence does not comment on submarine operations.’ This stonewalling sentence is delivered with steely calm to anyone who seeks to garner information on the Royal Naval Submarine Service (RNSS), the ‘special breed’ of men (soon to be joined by women) who dive into the depths aboard Britain’s nuclear submarines. The sheer difficulty of getting any information out of the MoD on this subject makes The Silent Deep, the new history of the RNSS by Peter Hennessy and his research assistant, James Jinks, all the more remarkable. Over 800 or so pages, they have managed to reveal to the world, using copious documents and the testimonies of submariners themselves, to tell a tale that, in its frankness, has surprised even Royal Navy veterans. It is a testimony to the skill – and charm – of Hennessy, perhaps Britain’s most famous contemporary historian.

Such achievements do not stop some academics, however, dismissing Hennessy as ‘not a real historian; he just deals in gossip’. That comment may be inspired by envy, but it also reveals a lingering contempt for the pursuit of ‘contemporary history’, that somehow, what Niall Ferguson describes succinctly as ‘history within the memory of some persons now living’, is not real history.

Ferguson is a former editor of the Journal of Contemporary History (JCH), which celebrates the 50th anniversary of its first publication, in January 1966, with a gathering of distinguished historians at London's Wiener Library on 12 November. Few publications have done more for the cause of contemporary history and, as current editor Richard J. Evans points out, over the last half century the JCH ‘has remained true to the vision of its founders as a pioneering academic periodical that presents new research and explores new fields while remaining accessible to the non-specialist lay reader’.

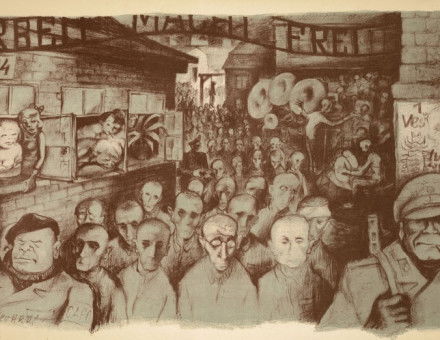

Those founders, George L. Mosse and Walter Laqueur, were part of that great generation of Jewish emigres who, having fled Nazi Germany, enriched their new country with their talents and pioneering techniques. Mosse was a scion of the family which owned the liberal broadsheet, the Berliner Tageblatt. Having fled on the accession of Hitler, he eventually gained a place at Cambridge before embarking on a distinguished academic career in the US, whose most famous fruit was his 1975 study of Nazism as a political religion, The Nationalization of the Masses. Laqueur, born in Breslau (now Polish Wroclaw), fled to Palestine in 1938; both of his parents, who stayed behind, were murdered by the Nazis. He, too, built an academic career in the US, one mixed with regular forays into the worlds of journalism and think tanks.

The JCH was born after Laqueur was appointed director of London's Wiener Library, whose mission was to collect sources and documentation on Nazi ideology. The JCH was established in the same building, then in Fitzrovia, and the publisher George Weidenfeld, another exile from Central Europe, agreed to handle its production and distribution. Unsurprisingly, the first issue was devoted to the subject of fascism. It was the journal's ‘special issues’ (insisted on by Weidenfeld, always with one eye on the commercial) that became the hallmark of the JCH. Recent examples – the edition on the Fischer Controversy and the origins of the First World War, edited by Annika Mombauer (2013), and Matthew Frank and Jessica Reinisch’s tackling of refugees and the European nation state (2014) come to mind – have proved both timely and prescient. The next volume, the 50th anniversary edition, will be the last edited by Stanley Payne.

The JCH has played a crucial role in establishing contemporary history as a (largely) respected discipline, as well as encouraging welcome growth in the study of International Relations. And, like History Today, it has sought to present serious history to a non-specialist audience, never an easy task. As Laqueur wrote: ‘Contributors had to be convinced that readability was an important consideration and that there was a difference between a dissertation in which the author had to enumerate everything he had ever read and an article for a journal of this kind.’

Paul Lay is the editor of History Today.