ISIS and Islam

History is often skewed to support a chosen view, but, for ISIS, a past derived from questionable sources has proved a powerful weapon.

ISIS is an organisation as fascinating as it is abhorrent. It is not too cavalier to characterise it as the world’s bloodiest historical re-enactment society.

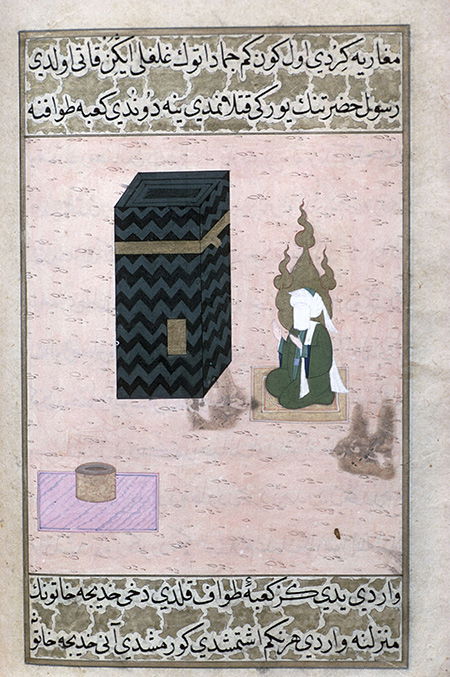

The chief conceit upon which ISIS bases its legitimacy is that it is practising Islam as lived by the prophet and his companions. Surrounded by enemies of Allah on all sides, it is its duty to wage jihad to give God’s sovereignty physical form. As Muhammad fought the polytheists of Mecca after fleeing to Medina, so must ISIS attack those it sees as analogous to the prophet’s foes: in effect, all who reject its version of Islam.

The group’s online magazine, Dabiq, contains a regular feature entitled ‘From the Pages of History’. Complete with pictures of its fighters in mock-medieval dress, ISIS presents examples of exemplary warrior behaviour from Islam’s early history to exhort its sympathisers to Holy War. The closing paragraphs of a piece on ‘The Expeditions, Battles and Victories of Ramadan’ make this purpose explicit:

This is how as-Salaf as-Sālih (the Righteous Predecessors) were in it! Jihad, battles, and action … do not allow another Ramadan after this one to pass you by except that you have marched forth to fight for Allah’s cause.

ISIS is hardly innovative in looking to the past to build a purer Islamic present. Its insistence that the true faith only existed in the generation of Muhammad and his immediate successors is taken in large part from the writings of modern Islamist intellectuals, such as the Egyptian Sayyid Qutb. Originally a nationalist whose development of extreme Islamist doctrines led to his execution in 1966, Qutb argued that all societies that fail to abide by the totality of the sharia, even if they are ostensibly Muslim, are in the same state of jāhilīyya (ignorance) that Islam came to correct. Allowing this situation to continue is unconscionable: it disrupts the natural order of God’s law and enslaves man to authorities beyond the only true authority, Allah.

For Qutb, preaching correction was not enough. As he says in his influential tract, Milestones: ‘Since the objective of the message of Islam is a decisive declaration of man’s freedom … in the actual conditions of life, it must employ jihad.’

Qutb delved into the annals of Islamic history to justify this verdict. He extracted telling episodes and choice quotes from the mouths of the men who fought in the armies of the seventh-century Arab conquests. One scene that he seems to have taken from the 10th-century historian and exegete Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari, for example, has an Arab warrior declare to his Persian enemy that he is impelled by God to fight them until they either convert or until he is martyred. There can simply be no other way.

Qutb’s philosophy became terrifyingly influential in Egypt and across the Middle East. Among the disciples who sought to enact the master’s creed was Ayman al-Zawahiri, one of the founders of al-Qaeda.

Yet the use to which Qutb and ISIS put the texts of Islamic history begs an important, if not obvious, question. Is this legitimate scholarly use or lethally misleading abuse?

Trying to reconstruct the early history of Islam from the texts of the tradition is a task fraught with difficulties. Cardinal tomes like the History of the Prophets and Kings by al-Tabari are not primary sources for the history of the faith. They were compiled about two centuries after the events they describe and were ultimately reliant on a mercurial oral tradition that forgot as much material as it remembered.

Moreover, these memories, as ever with oral tradition, were shaped to suit the assumptions and expectations of later ages, rather than to transmit accurate recollections from generations past. The Islamic histories often read more like historical romances than the accurate record they pretend to be, containing stereotyped episodes like that of the Muslim warrior explaining the philosophy of jihad to a Persian general. It clearly suits a literary scheme, but the notion that it captures more than an echo of the chaotic events of the seventh-century conquests borders on the incredible.

How, then, is it possible to reach beyond the rhetoric better to understand the first century of Islam? This is a question that has dominated recent western work on the subject and a question that is impossible fully to answer. By widening the source base and stressing the importance of earlier texts outside the Islamic tradition, however, it is possible to try to get a more nuanced idea of the complex and dramatic events that shaped the career of Muhammad and propelled his followers to conquest.

Two interesting accounts preserved in the pages of the Byzantine chroniclers Theophanes the Confessor and the Patriarch Nicephorus, for instance, tell the story of the outbreak of the seventh-century conquests in a manner that directly challenges the assumptions of the Islamic tradition. These histories may admittedly be compilations made later than the seventh century, but there is good reason to believe that they rely on written evidence contemporary to the events they describe: a more stable means for the transmission of information than an oral tradition.

They explain the outbreak of the supposedly Islamic invasions of the 630s in a manner that hardly resonates with the jihadist notion of Arabs moving out of the peninsula, driven solely by religious zeal. Rather, Theophanes and Nicephorus paint a picture of the breakdown of Rome’s relationships with the Arab clients to whom it had entrusted the security of its desert frontier. This rupture had solely material causes. After a long war with Persia, the Empire’s coffers were empty. Theophanes reveals that, when the Arab allies came to collect their wages, they were dismissed empty handed by an imperial official.

This decision had major strategic ramifications. An earlier raid on Palestine from the Hijaz had been repelled, but Theophanes records that the spurned Arab clients ‘went over to their fellow tribesmen, and led them to the rich country of Gaza’. The collapse of Rome’s eastern provinces, therefore, appears – as was the case with the fall of Rome in the West – to have come about, at least partially, when federate forces deprived of payment came to realise that biting the hand that feeds can lead to greater rewards.

Holy War, for some of the men remembered as the soldiers of Islam, did not enter into consideration. ISIS, therefore, is in hock not only to a novel Islamist ideology that rejects centuries of Islamic thought and practice. They are also in hock to bad history.

James Wakeley is studying for a DPhil in late Roman and early Islamic History at the University of Oxford.