Weathering Storms

In the wake of Hurricane Irma we are reminded that the effects of natural disasters are never entirely natural.

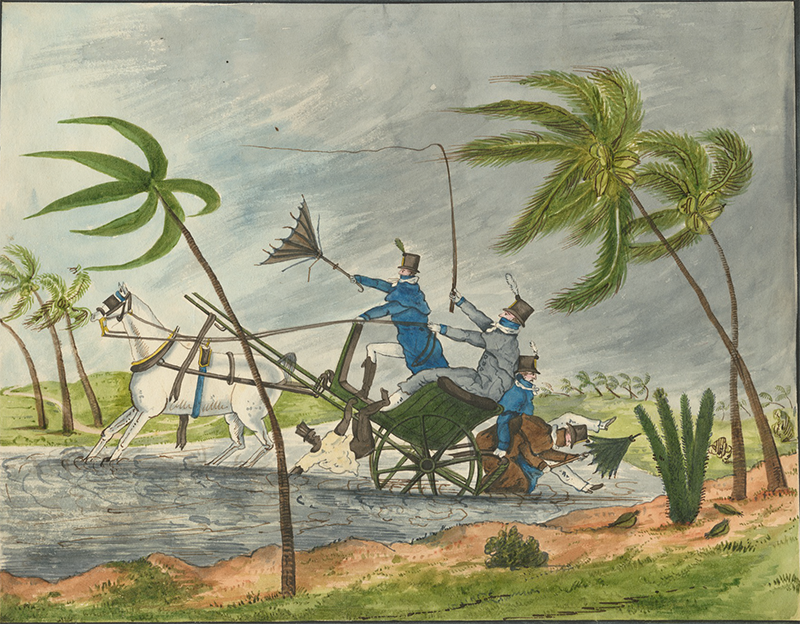

For most of the 19th century, besides being aware of the hurricane season (June-November), there was little that those living in the Caribbean could do to predict the arrival of storms. As rains and winds began to pick up, the wealthy took shelter in the cellars of their stone houses, while the wooden shacks of the enslaved population offered almost no protection. When a storm hit, the majority of the enslaved population simply found themselves having to try and survive days and nights out in the open, exposed to the weather. Even when slavery was abolished, the distribution of land and power in the Caribbean meant that the population of former slaves remained the most vulnerable, despite being notionally free to choose where they lived. The power of the landowning class to evict labourers meant that the majority lived in transportable housing, built without nails and without any permanent anchor in the soil.

For most of the 19th century, besides being aware of the hurricane season (June-November), there was little that those living in the Caribbean could do to predict the arrival of storms. As rains and winds began to pick up, the wealthy took shelter in the cellars of their stone houses, while the wooden shacks of the enslaved population offered almost no protection. When a storm hit, the majority of the enslaved population simply found themselves having to try and survive days and nights out in the open, exposed to the weather. Even when slavery was abolished, the distribution of land and power in the Caribbean meant that the population of former slaves remained the most vulnerable, despite being notionally free to choose where they lived. The power of the landowning class to evict labourers meant that the majority lived in transportable housing, built without nails and without any permanent anchor in the soil.

Being forced into the open during a hurricane must have been a harrowing experience, made worse by the indelible mark left on the Caribbean colonies by the sugar plantations. The forests of the Caribbean had been consumed by the sugar industry: timber built the British settlements and fed the boiling houses. Where forest survived in small copses, it was purposely chopped down lest it provide cover for escaping slaves or, in line with the miasmatic theory of disease, prevent the passage of fresh air and lock in ‘bad’ tropical air which encouraged disease. The scale of the deforestation across the British Caribbean was immense, but it was particularly bad on Barbados, which was in effect one huge sugar plantation and had been dependent on imported timber since 1760. In the event of a hurricane, the reality of deforestation meant that for those forced into the open there was no natural cover to be sought. What is more, where tree cover would once have acted as a windbreak, impeding a hurricane’s speed, the winds that lashed both people and buildings were unbowed in their ferocity.

The damage caused by deforestation did not end there; without tree roots there was little to bind the soil. Thus, from the 17th century, soil erosion plagued the British Caribbean colonies. Wherever trees were cut down and sugar planted, landslips soon followed, especially in the face of the deluges brought by hurricanes. Eyewitnesses to the Barbadian hurricane of 1831 report seeing huge sinkholes opening in the ground, which swallowed livestock whole. The fragility of the soil not only created another hazard for those without shelter, but it had consequences for the capacity of British Caribbean colonies to feed themselves in the event of a hurricane. Sugar cultivation monopolised nearly all agricultural land and it was easily swept away by hurricane-force winds. In small patches around their plantation shacks, enslaved people were permitted to grow other vegetables. However, enslaved people, at least in Barbados, preferred to plant plantain and guinea corn for its relatively high resale price, thus allowing them a meagre level of economic autonomy, compared with yams, a deep-rooted tuber that usually survived hurricane winds. Just like the timber required to rebuild property, food had to be regularly imported following hurricanes to avoid starvation.

Until the establishment of telegraph lines to the British Caribbean in the 1880s, the delay in communications between Britain and its Caribbean colonies meant it usually took at least a week for knowledge of disaster to arrive in Britain. The most immediate relief, therefore, usually arrived from neighbouring islands in the days following a disaster. This relief usually consisted of potted beef and pease pudding; items that, given the limited capacity for long-term food storage in the 19th century, had some chance of surviving the journey between islands.

The British colonial authorities had no set way to respond to disasters and provide relief in the Caribbean. Yet certain informal patterns emerge across the 19th century. The most striking of these is that the protection of colonial and other forms of private property always took priority over providing relief. Given the inherently fractious nature of a society founded on slavery, the deployment of armed militias was usually the first form of organised response. In 1831, enslaved people were arrested or even shot for attempting to stockpile what corn and other foodstuffs could be salvaged from the wreckage of plantations. After the abolition of slavery, this pattern of response remained unchanged. In 1907, following an earthquake that levelled Kingston, Jamaica, the West India Regiment was armed and deployed on horseback to guard places of value to the colonial regime.

Following the impact of hurricane Irma, much debate has centred on the scope of aid Britain should provide to the Caribbean. In the 19th century, there was debate, but of quite a different nature. Relief was never a given and a justifiable case for relief had to be made to a Parliament wary of the Caribbean planters deliberately overestimating their losses. The wrangling over the scope of relief could take years to resolve. What is more, once it arrived, there was little oversight into what happened with it. Visitors to Dominica in 1836 found that much of the housing for apprenticed labourers had never been rebuilt despite Parliament allocating money specifically for that purpose.

The interaction of natural phenomena on the 19th-century Caribbean shows that how humans shape the environment and organise themselves socially can have a significant impact on the scale of a disaster. Global climate change increases the potential for natural hazards to impact not just on Caribbean societies but societies around the world and it is the case, now more than ever, that we need to understand that it is within our capacity to limit their impacts. No disaster is ever entirely natural.

Oscar Webber is a PhD student at the University of Leeds, researching British responses to natural disaster in the 19th-century Caribbean.