The Pilgrim Settlers Before the Mayflower

23 years before the Mayflower, the first pilgrim settlers to America tried, and failed, to settle in Newfoundland.

This year, the US looks back four centuries to an intrepid band of refugees making a perilous home in New England. The Mayflower pilgrims had been outlaws in England, members of an underground church known as the Brownists or Separatists. They believed church should be a voluntary community rather than a compulsory state religion. For their refusal to submit to the Church of England they had faced raids, prison, exile and death for the previous 60 years.

The pilgrims were not the first British settlers in North America. The officially sanctioned colony of Jamestown, Virginia, was 13 years old in 1620 and Roanoake colony, founded in the 1580s, had disappeared. What is less well known is that the Brownists themselves had made a previous expedition to North America. They had attempted to become the pilgrim fathers as early as 1597, trying to settle in Newfoundland.

The idea for a Canadian colony came out of the crisis surrounding the execution of the Separatist leaders Henry Barrow and John Greenwood on 6 April 1593, the morning after Parliament passed the Seditious Sectaries Act against them. The surviving Brownists were effectively banished by the Act, on pain of death, and so a large part of the underground church moved to the Netherlands.

The more dangerous members, however, including their pastor Francis Johnson, were kept in prison in London. They petitioned the government for release, to no avail, until in March 1597 they came up with a new plan. The imprisoned Brownist leaders proposed to the Privy Council that they should be released into colonial expedition to Canada. The colony would claim fishing and hunting territory for England, the Separatists said, and ‘greatly annoy that bloody and persecuting Spaniard’, ensuring that the Americas did not fall entirely into the hands of the Catholic empire.

The Separatists’ own reasons for going were similar to the later Mayflower pilgrims – to found a settlement where they would be free to practise the faith that made them outlaws in their homeland, transforming them into state-sanctioned pioneers and gaining their church a measure of authorisation for the first time. This first attempt was a more desperate gamble than the 1620 journey, though. These Brownists were prisoners whose lives were on the line, escaping their fate by going to a continent where no English settler had survived. The Mayflower pilgrims in contrast had already escaped English law before 1620 by migrating to the Netherlands and were embracing the dangers of North America out of a sense that God had called them to the promised land.

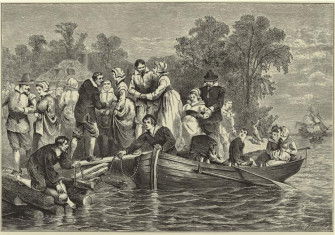

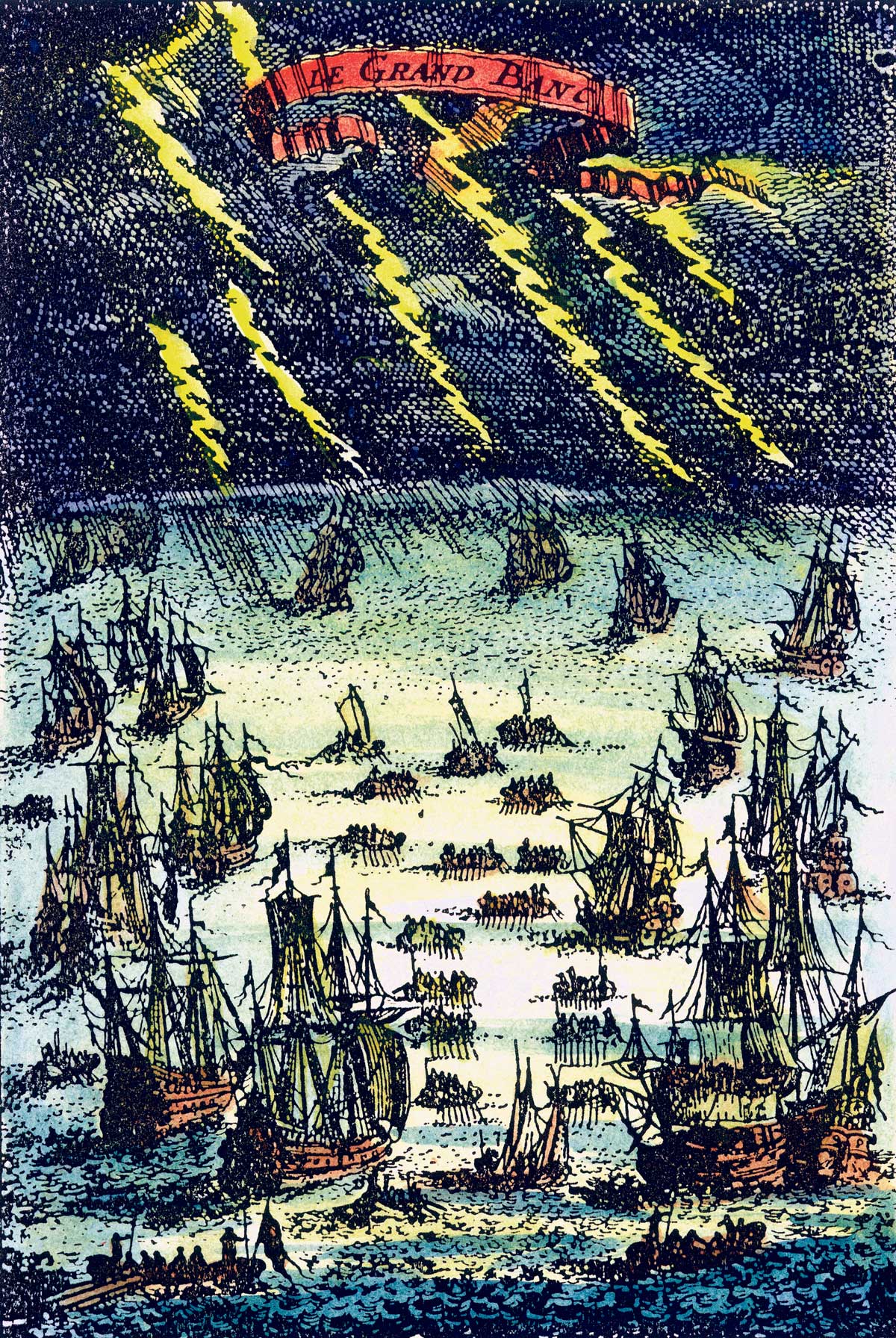

Four Separatists made the journey to Newfoundland in April and May 1597 in two ships, the dubiously named Hopewell and Chancewell – a generous provision compared with the Mayflower, which on its own had to carry 102 passengers with all their possessions and provisions. The four included Francis Johnson, the surviving leader of the movement, who travelled on the Hopewell, and his brother George on the Chancewell.

Arriving in Canadian waters in May, the ships were separated in the fog and the Hopewell reached its destination, the Magdalen Islands in the Gulf of St Lawrence, alone. They found the fishing there fantastic, catching 250 cod in an hour with four lines, though their attempts to catch walruses ended in them fleeing for their lives. Their greater problem was that the place was already rather crowded, with numerous French and Spanish ships and hundreds of indigenous Canadians, who had come from the mainland to hunt and fish. After a skirmish with the Europeans, the captain decided to try the north coast of the gulf, but the crew refused and turned the ship for home.

The Chancewell, meanwhile, found itself at Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, where it hit the rocks. The crew managed to get it into a bay, but it was raided by more French sailors who took all the settlers’ possessions. The captain offered his two Separatists a choice: stay on the island and be ‘devoured by the wild’; surrender to a French ship where ‘they should be urged to hear Mass’; or join the crew in trying to hijack a Spanish ship. George was too frightened to choose and asked the captain to make the choice for them, but he refused.

At that moment they had the extraordinary luck – or providence, as the Separatists saw it – to spot the Hopewell passing on its return journey, and they flagged it down. Once reunited, they negotiated the return of some of their lost possessions and seized a French man-of-war and so were at least able to return home with as many ships as they started with. The Canadian adventure was over and the Separatists decided to settle in Amsterdam.

The Newfoundland expedition developed a tradition that the Mayflower pilgrims followed. Francis Johnson’s congregation also seem to have made two further attempts to settle in the new world before 1620, about which very little is known except that they ended in disaster. The journey of 1597 has had little recognition as an early colonial attempt on North America, partly because nothing came of it, but also because even those involved seem to have had little interest in the story. Francis Johnson wrote eight or so books without ever making any mention of the expedition. The captain of the Hopewell published his log, containing details of their explorations and their encounters with the French, but made no mention of any would-be settlers on board, apparently not being particularly keen to associate his name with the transportation of felons. George Johnson wrote a brief account of the journey, but it is buried in a much longer account of his theological and personal quarrels with his brother.

Because of this, little is known of the Separatists’ feelings about the expedition or the destination, their hopes, fears or disappointments. We do know that what they attempted and failed was achieved by their spiritual brothers and sisters 23 years later.

Stephen Tomkins is the author of The Journey to the Mayflower: God’s Outlaws & the Invention of Freedom (Hodder & Stoughton, 2020).