The Scribes of the Salisbury Magna Carta

New research has, for the first time, identified the scribes of Magna Carta.

King John’s 1215 grant of Magna Carta, of which we are currently celebrating the 800th anniversary, is known from four surviving copies, two in the British Library, one in Lincoln Cathedral and another in Salisbury Cathedral. On February 2nd-4th, 2015 these four documents were brought together, perhaps for the first time, at the British Library, before an audience of 1215 people selected by ballot. This event facilitated a detailed comparison of the documents as part of the major Magna Carta project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and directed by Nicholas Vincent of the University of East Anglia and David Carpenter of King’s College London. Part of the work of this project has been analysing the hands of the early grants and reissues of Magna Carta. On June 14th, 2015, the team announced that their research shows the Lincoln and Salisbury charters to have been written by scribes at those very ecclesiastical institutions. Our independent research on the Salisbury Magna Carta suggests that same conclusion, though using different evidence.

King John’s 1215 grant of Magna Carta, of which we are currently celebrating the 800th anniversary, is known from four surviving copies, two in the British Library, one in Lincoln Cathedral and another in Salisbury Cathedral. On February 2nd-4th, 2015 these four documents were brought together, perhaps for the first time, at the British Library, before an audience of 1215 people selected by ballot. This event facilitated a detailed comparison of the documents as part of the major Magna Carta project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and directed by Nicholas Vincent of the University of East Anglia and David Carpenter of King’s College London. Part of the work of this project has been analysing the hands of the early grants and reissues of Magna Carta. On June 14th, 2015, the team announced that their research shows the Lincoln and Salisbury charters to have been written by scribes at those very ecclesiastical institutions. Our independent research on the Salisbury Magna Carta suggests that same conclusion, though using different evidence.

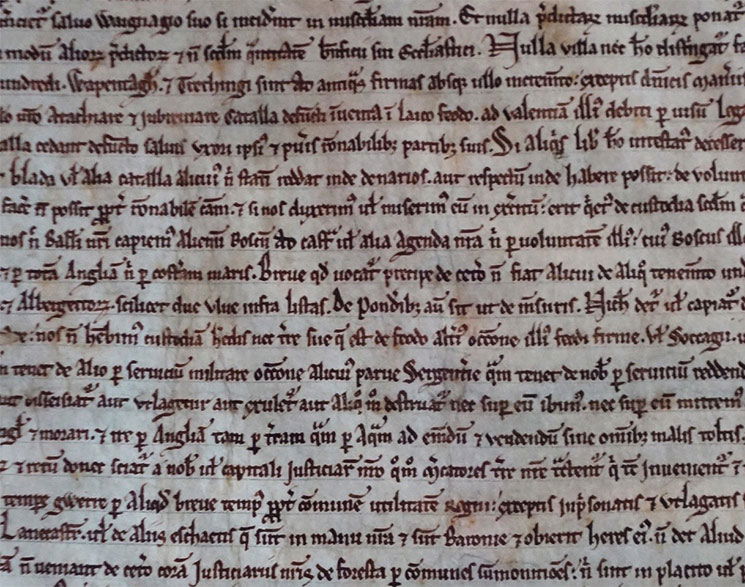

Of the four 1215 copies of Magna Carta, the one whose appearance differs most obviously from the others is that in the Salisbury Cathedral archives, which written in a different style of handwriting. While some scholars have noted this book hand, and indeed suggested an ecclesiastical scriptorium as a possible place of origin, others maintained that it must have been produced in the Chancery, the king’s centralised office of scribes.

Since neither Wiltshire nor Salisbury were mentioned in the list for the distribution of the writ for the publication of Magna Carta or in the schedule of charters issued, some scholars proposed that the Salisbury copy was not produced by the Chancery at all, and was even perhaps made a few years after 1215. What seemed to be at stake here was the authenticity of this version of the 1215 Charter. If it was not issued by the Chancery, it may not be ‘real’. However, our evidence, together with that of Magna Carta Project team, suggests that the chief issue here was our understanding of the methods of dissemination of royal charters in this period: if ecclesiastical scriptoria were responsible for writing these charters and then having them sealed, it changes our understanding of the use of written documents in government in the early 13th century.

Emily Naish, the archivist of Salisbury Cathedral, has recently made the important discovery that there is a copy of the text of the surviving Salisbury copy in another manuscript (ff. 5v-7v of the Salisbury Cathedral cartulary, ‘Liber Evidentiarum C’, compiled before 1284). While there has been discussion of the possible date of the Salisbury Magna Carta, there had been, until recently, few serious attempts to identify the location of its scribe and therefore the place where this copy was produced. Further examination of the handwriting of known Salisbury scribes from the first decades of the 13th century convincingly indicates that the Salisbury Magna Carta was written by a scribe from Salisbury Cathedral.

The Writing of the Salisbury Magna Carta

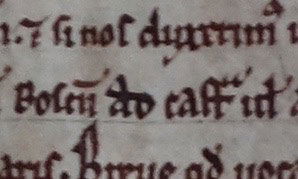

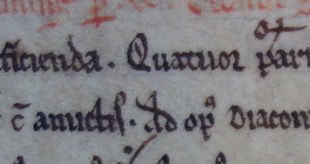

The style of handwriting used for Salisbury’s Magna Carta is called a Textualis hand rather than the diplomatic hand used on the other copies. An example can be seen in this rather odd yellowy image. It is regular and shows few idiosyncratic and therefore identifiable features. One repeated and distinctive practice in this text, however, is the conjoining of enlarged a and round-backed d, where the back of d crosses through the bow of a, as in the image here.

There is far more one could say, but this collection of data is sufficient to build a strong case for the production of the Salisbury Magna Carta by a Salisbury scribe. A number of other surviving manuscripts and texts exist to support this claim, by multiple Salisbury scribes that are, and always have been, in situ in the archive that created them. Some of these are closely datable to the 1215 date of the Magna Carta.

The Register of St Osmund

The Register of St Osmund, now housed in Salisbury Cathedral Archive, contains the work of many scribes who must have been at Old Sarum and Salisbury (Old Sarum was abandoned for the new Salisbury Cathedral foundation in 1220). This Register, until recently deposited in the Wiltshire County Record Office, is generally dated to c.1220, five years after Magna Carta, but it may have been begun slightly earlier in readiness for the move.

The earliest scribe in the Register who copied the opening pages has handwriting that is more formal than that associated with Salisbury’s Magna Carta, but there are notable similarities, including as seen here, the occasional use of a conjoined enlarged a and d in ‘ad’, where the round-backed d pierces the bow of a.

The close comparison of this, and of many other letter-forms and punctuation marks (as discussed in detail here) is certainly suggestive of the Magna Carta scribe’s work being a Salisbury product.

The identification of the scribe of this copy of Magna Carta as from Salisbury, together with the evidence of a distinctive tear at the bottom of the Charter where a seal would have been, suggests that it was produced by Salisbury and then presented for sealing with the Great Seal. This tells us important things about how Magna Carta was disseminated and about the preparation and circulation of government documents in the High Middle Ages. Although the royal confirmation of documents prepared by the beneficiary was commonplace in an earlier period, it seems that the practice persisted in 1215, despite the enormous developments in royal administration at that time.

One of the most exciting things to emerge from this research is how much more there is to learn about textual production in the medieval period. Major ecclesiastical institutions, such as Salisbury, Worcester and Lincoln, have as much to offer researchers as do the large repositories that have gathered discrete and disparate collections. Resources must be made centrally available for these institutions comparable to the national and university libraries and archives if we are to truly gain access to the rich documentary heritage that survives from medieval Britain.

Acknowledgements

Elaine Treharne should like to thank the Dean and the Chapter of Salisbury Cathedral for their permission to work in the Library and Archive. In particular, many thanks go to the Canon Chancellor, Reverend Canon Edward Probert, and the Archivist, Mrs Emily Naish.

Elaine Treharne is Professor of Humanities at Stanford University. Andrew Prescott is Professor of Digital Humanities at Glasgow University.