A Woman's Place...

Sarah Gristwood considers some earlier female MPs who might have given Mrs Thatcher a run for her money.

In the heated discussions that followed Margaret Thatcher’s death, one word came up with notable frequency: divisive. Dividing not only right from left, hagiographers from haters, but women – those who would never have voted for her but now found themselves faced with the old question of whether they should, nonetheless, hail her achievements as a groundbreaker. After all, it would appear that in almost a hundred years of parliamentary politics there have been few other talismanic female politicians, at least, not until recently. But well before Betty Boothroyd, Shirley Williams, Mo Mowlam or Margaret Beckett, there were some memorable figures among the earliest women MPs.

In the heated discussions that followed Margaret Thatcher’s death, one word came up with notable frequency: divisive. Dividing not only right from left, hagiographers from haters, but women – those who would never have voted for her but now found themselves faced with the old question of whether they should, nonetheless, hail her achievements as a groundbreaker. After all, it would appear that in almost a hundred years of parliamentary politics there have been few other talismanic female politicians, at least, not until recently. But well before Betty Boothroyd, Shirley Williams, Mo Mowlam or Margaret Beckett, there were some memorable figures among the earliest women MPs.

When Lady Astor entered the House at the end of 1919 she was in fact the second woman to be elected. The first had been Countess Markievicz (1868-1927), elected in 1918 for a Dublin constituency, who as a member of Sinn Fein was never, in fact, going to take the seat she had contested only as part of the battle for Home Rule. Jailed for her part in the Easter Rising, she fought her campaign from Holloway prison.

Con Markievicz was a colourful figure, who posed for publicity pictures revolver in hand, but Nancy Astor (1879-1964) could match her. As Britain’s first female MP she was something of an anomaly; an American and a millionaire’s wife, whose personal obsession was the temperance movement. Perhaps it took the confidence of that social background to speak as the only ‘Lady Member’. The second lady member, the Liberal Margaret Wintringham (1879-1955), like Lady Astor, inherited a seat from her husband; so too did the third, Mrs Mabel Hilton Philipson (1881-1951), a former star of musical comedy. This would remain a regular pattern. It was left to the Labour Party to provide the first women who entered the House another way.

Margaret Bondfield (1873-1951) – ‘our Maggie’ to her Northampton constituents – was a lacemaker’s daughter who had started work at 14 and came to London with just £5 in her pocket. Her rise has a storybook charm – she first read about the Shop Assistants’ Union in her fish and chip wrapping – but this Cinderella’s payoff was to ascend through the ranks of that union. In 1923, the year in which she was elected to Parliament, she became Chairman [sic] of the General Council of the TUC.

Bondfield and the two other Labour members elected alongside her were the first of the new influx to have worked professionally in the political sphere – and also the first single women. This Maggie became the first woman minister and then Cabinet minister. She was Under-Secretary of State for Labour in 1924 and, five years later, Minister of Labour with a Cabinet seat. However Bondfield never did become an icon and lost her traditionally Conservative seat of Northampton in 1924.

Is it relevant that Bondfield was never a glamorous figure? Not as memorable as Lady Terrington, who did her electioneering on horseback, or as the Conservative Duchess of Atholl, the first woman member for Scotland, who would become known as ‘the Red Duchess’ for her sympathies with the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War and who once rose to her feet to explain to the House the precise nature of female circumcision?

This invites the vexed question of the links between a politician’s effectiveness and the persuasiveness of their public identity and whether they can present an image vivid enough to strike a chord. Thinking of Mrs Thatcher’s easy access to the potent, ready-made imagery of the nation’s nanny, it is tempting to ask whether this comes any easier to the women of the right. The answer, as history proves, is ‘not necessarily’.

The theory is given the lie most obviously by Barbara Castle, who Patricia Hewitt said ‘should have been Labour’s – and Britain’s – first female prime minister’. Minister for Overseas Development and then Transport; Secretary of State for Employment and then for Health and Social Services; but an inspiration even beyond her attempts to reform Britain’s industrial relations, her welfare reforms and her sponsorship of the Equal Pay Act.

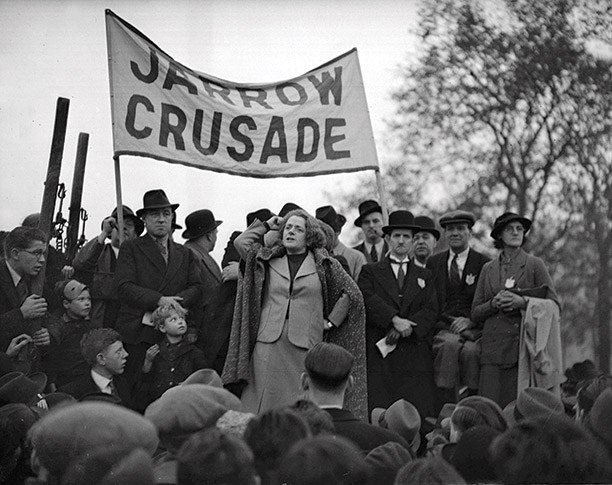

Back in the 1920s, two Labour women had blazed a trail. Jennie Lee (1904-88), the miner’s daughter elected to the House at 24, came to be considered by many the best arts minister Britain ever had, but memory of Lee’s own parliamentary career has tended to be overshadowed by her legend as Nye Bevan’s ‘dark angel’. As famous in her days was Ellen Wilkinson (1891-1947), the ‘Pocket Pasionaria’, the ‘Fiery Atom’ – as MP for Jarrow, an instigator of the famous march; and as ‘Red Nellie’, a hugely popular public personality. She was Parliamentary Secretary in Churchill’s wartime coalition and Minister of Education under Attlee.

Wilkinson articulated a number of the issues that continued to face female politicians. ‘I have women’s interests to look after but I do not want to be regarded purely as a woman’s MP’, she said. But she, like the other early women MPs was aware of being, as representative of her sex, expected to serve a dual constituency. Are these the grounds on which we complain that Thatcher left no feminist legacy? When ‘Blair’s Babes’ first came into the Commons, I had occasion to ask some whether they had ever heard of Wilkinson. They hadn’t. On several different levels, that ignorance seems a pity.