The Original Anti-Vaxxers

When widespread vaccination was introduced there were objections – some justified, some not.

Anti-vaccination protests are nothing new, although in the past they did have some justification. When Edward Jenner introduced smallpox inoculation at the end of the 18th century he was widely derided as yet another quack trying to make a quick fortune. Envious rivals were swift to point out his lack of professional qualifications, while one satirist imagined his children turning into cows after being vaccinated:

There, nibbling at thistle, stand Jem, Joe and Mary

On their foreheads,

Oh, horrible! Crumpled horns bud …

Jenner’s technique sounded bizarre and the testing programme was perfunctory. After learning that dairymaids apparently became immune to smallpox after catching cowpox, he embarked on an unorthodox experiment. First, he inoculated his gardener’s son with lymph taken from a woman’s cowpox blister and, two months later, deliberately exposed him to smallpox. The boy remained healthy, as did a handful of further conscripts: Jenner was ready to launch his new procedure.

Doctors were already practising variolation (variola is Latin for smallpox), the Turkish antidote imported by Mary Wortley Montagu, which involved inducing a (hopefully) mild form of the disease to stimulate resistance. Risky and unpleasant – but it usually worked. In contrast, Jenner’s counter-intuitive recommendation was to contaminate human bodies with matter from a creature lower down God’s hierarchy. These suspicions were confirmed when patients reacted badly, probably because of poor medical hygiene. In his anti-vaccination propaganda, Dr Rowley of Oxford showed a boy with heavily swollen glands, remarking that he seemed to be ‘assuming the visage of a cow’.

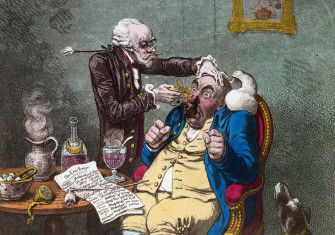

In a savage caricature, James Gillray played on contemporary fears by mocking a packed hospital clinic. Prominent in the centre is Jenner, wielding the spiked metal instrument used for scraping patients’ skin. To his right stands a scruffy charity boy holding a tub of ‘Vaccine Pock hot from ye Cow’ for Jenner to smear into the wound on the terrified woman’s arm. Above them looms a picture referring to the biblical story of Aaron blasphemously encouraging the Israelites to worship a golden calf. On the right, a pregnant woman is vomiting up a small cow, surrounded by people with cow-like tumours sprouting from their faces.

Opposition to Jenner slowly faded, but in 1853 the debates shifted gear when the government made it compulsory to vaccinate all newborn babies. What sounds like a sensible health measure proved enormously controversial, provoking riots and demonstrations. Antagonists from opposing camps were at loggerheads about two main issues: the clinical risks and benefits, and the right of the state to dictate an individual’s actions.

The anti-vaccinators voiced some powerful arguments. The procedure was long, painful and sometimes life-threatening. Practitioners scored cuts into a baby’s arm, rubbed in pre-prepared lymph and, eight days later, harvested new lymph from the blisters, which was then recycled for treating the next tiny patient in line. Parents might have been happier about subjecting infants to this ordeal if they could be confident it provided immunity. But, although data collection improved through the century, there was no incontrovertible evidence that vaccination guaranteed protection.

Inserting alien material threatened an innocent baby’s God-given purity. Parents not only objected to polluting their babies with animal matter, but also insisted that passing bodily fluids between children enabled infections to be transmitted. Perhaps insanity and progressive diseases were present in the serum – and suppose a privileged infant received cells from one that was Irish or Black?

Anger was exacerbated by conflicts over the cause of smallpox. Was a specific germ responsible, or did illness stem from a miasma of foetid air? Reformers agreed that the filthy, overcrowded slums needed to be cleaned up, but some health experts – Florence Nightingale, for instance – insisted that cleanliness offered a sufficient solution. Such arguments led only too easily to declarations that poor people were guilty of living fecklessly, of spreading disease through their failure to keep themselves clean and well-nourished.

The virus was too tiny for even powerful microscopes to detect and sceptics denounced doctors as scaremongers. Anti-vaccinators devised various strands of persuasive soapbox rhetoric. Should freeborn Britons be subject to the whims of the medical profession? Was vaccination just another tactic for the upper classes to lord it over decent hard-working people? In any case, was there any point in spending good public money on the impoverished dregs of society?

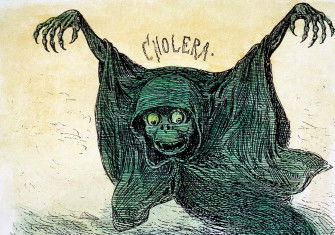

In 1898 a new clause was introduced permitting parents to declare themselves Conscientious Objectors and withdraw their child from the national programme. A Punch cartoon articulated middle-class complaints that this governmental capitulation would encourage smallpox to ravage the country. Trampling on a copy of the Lancet, Death brandishes an anti-vaccination banner as civilisation crumbles about him. The title De-Jenner-ation puns on the flipside of evolution and progress – the possibility of degeneration. As populations expanded and societies became more democratic, fears about personal and national deterioration pervaded Europe. Anti-vaccinators whipped up chauvinist sympathies by coining bellicose slogans that emphasised pollution, depletion and contamination: the ‘Anglo-Saxon race – once the finest race of people – will sink into effeminacy, disease, and premature death’ proclaimed one prominent campaigner.

In a vain bid to satisfy everyone, soon after this caricature appeared the government pushed through compromise legislation that made the situation worse. To qualify for exemption, parents had to convince a magistrate that they ‘conscientiously’ believed vaccination would damage their child’s health. Opponents immediately pointed out that the strength of a belief is intangible and impossible to measure. Applications were often flatly rejected, thus exacerbating existing resentment among lower-class people, who regarded vaccination as yet another form of oppression. And then there was the gender question: suffragists were angered by legal debates about whether mothers had the right to obtain certificates.

By 1908 the government agreed that women could make responsible decisions on their own, but opting out became easier and many babies remained unvaccinated: not a positive move for the nation’s physical health, but a small step towards gender and class equality. And when war broke out in 1914, the term ‘Conscientious Objector’ acquired a different resonance.

Patricia Fara is an Emeritus Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge. Her next book will be Life after Gravity: The London Career of Isaac Newton (Oxford, 2021).