Mid-Victorianism

G.M. Young portrays the golden political calm and sense of cultural comfort at play in mid-Victorian England.

Within the two years 1846 and 1847 Thackeray, Livingstone and Bright, Dickens, Browning and Pugin reached their thirty-fifth birthday. Which of these is the most typical figure in the mid-Victorian picture, which is the most significant? But there is another name to be added to that list, and the popular verdict might be that the most significant and typical was—Samuel Smiles. Nor would that verdict be so very far wrong. If you ask what did it feel like to be alive and thinking in the fifties, Self Help and The Lives of the Engineers will get you some way to the answer. An example: the saying, Sanitas sanitatum omnia sanitas is always ascribed to Disraeli. He took it from Smiles, who quoted it from Julius Menochius and who he may have been I cannot find out. But it seems to me highly characteristic of the age that the Secretary of a Railway Company should spot and remember for his own use the saying of some Renaissance philosopher or physician. It was part of the sentiment of the time that we, too, were living in a great age and sharing the magnificence of the great ages of the past. Once when I had said something in that sense at the Sorbonne, Andre Siegfried declared that mid-Victorian England would rank in history with the age of Pericles, of Leo, of Louis XIV. And his French audience seemed to agree.

But first of all can we define it more exactly? Not forgetting that all such definitions are no more than labels, that there are no generations any more than there are centuries. But there are periods when the stream of time suddenly accelerates and that was one. Somewhere thereabouts is the time of transition from Early Victorian England to mid-Victorian England, and if you want a clearer limit, take Fielden’s Factory Act, 1847, the European revolution in 1848 and the collapse of Chartism on 10th April. Then call up some hypothetical central man, and ask—if you had dropped into his rooms one evening what would you have found him and his friends discussing, and on what assumptions would the conversations have proceeded? Let us suppose him to have been born about 1825 and brought up in good county or professional society, in a home where the Parliamentary report was read aloud, and perhaps re-debated in the evening, and the Edinburgh, the Quarterly, the Westminster and the Athenaeum were always lying on the table. He will remember, rather vaguely, the agitation of the elders over the Reform Bill: he may have peeped out of his nursery window to count the burning ricks, and see his mother turn dead white when the news was whispered—cholera in the market town. He grew up in an age of fear—fear of pestilence, fear of destruction, fear of revolution. Fear and hatred. His brothers were very likely officers of the yeomanry and kept their horses saddled and sabres sharpened to ride down and scatter the next assembly of starving peasants. And what all that might mean to an imaginative child is recorded for us by Dickens in, that wonderful nightpiece, in the forty-fifth chapter of the Old Curiosity Shop, of the Black Country about ’39.

By now our young person is old enough to read for himself, perhaps to take sides over Tract No. 90, and, whether he is at Rugby or not, he is beginning to feel the pressure of the Arnoldine discipline and the attraction of the Arnoldine ideal. He is looking forward to Oxford and Cambridge, and what will he find there? As no one can be asked to waste his time on that shapeless and tiresome sequel, Tom Brown at Oxford, I will recapitulate. A young man generously incensed over some case of village tyranny, asks why? Why am I rich and he poor? His Tractarian friends refer him to the Church, his tutor to the economists. Then the Junior Fellow puts a book of Carlyle’s into his hands and he sits up all night laughing and crying and shouting Carlyle’s phrases aloud.

Now Carlyle’s influence on the rising generation is one of the constituent elements in mid-Victorianism. And when once you have stripped off the fantastic mythology in which it is wrapped, his doctrine of history is not a thing to be neglected. The seer points out what is to be done: the hero does it. To maintain the achievement certain institutions create themselves or are created. They are the solid framework of the new order. Solid—too solid. Because that order is itself continually changing, until the framework becomes a cramping make-believe, which in the long run is exploded by the expansive power latent in every society. That is Revolution, and every revolution is the cause of suffering to innocent multitudes paying for the short-sightedness or arrogance, the laziness or selfishness, or their fore-runners. Then, out of the ruins, guided by the seer the hero frames the new order, and the cycle is renewed.

Apply this doctrine to Victorian England. In the thirties and forties, was it not at least arguable, that the framework created by the seers and heroes of the past had outlived its usefulness? To fear and hatred must be added something else—disappointment. What had the Great Reform Act done? Made of public life an arena for two aristocratic factions neither of which seemed capable of dealing with the problems of the new Industrial England—and it was into industry that the energy and courage of the nation seemed to be flowing.

And so, listening to that conversation, we should become aware of an ambivalence, as modern psychology might call it. On one side intense pride in the achievements of enlightenment and progress, invention and enterprise; and, on the other, a brooding fear of what might appear if cholera broke out or the underworld broke loose. The transition, the moral transition, from Early Victorian to mid-Victorian might be put in a phrase—fear abated, hatred subsided, pride remained. And in this process the illuminating phenomena, I should judge, were Fielden’s Factory Bill in 1847 and the Great Exhibition of 1851.

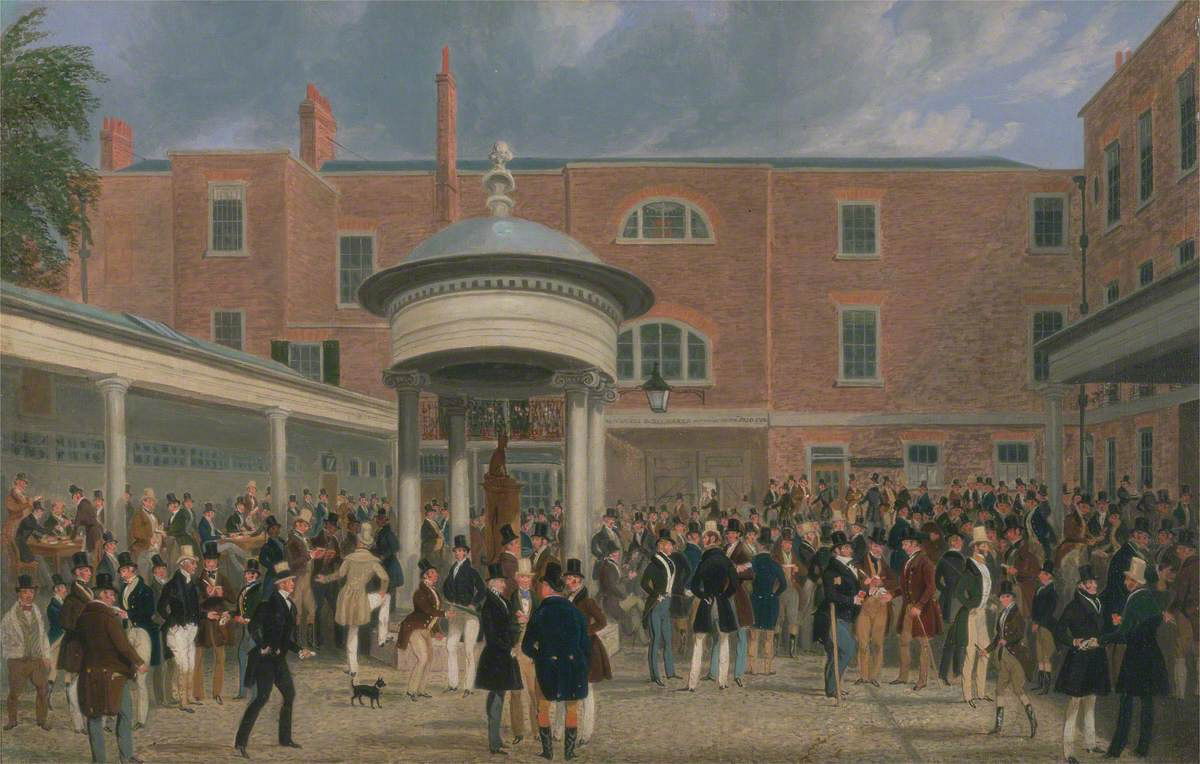

But behind them both was the final conversion of the country to Free Trade, and in particular the repeal of the Corn Laws. Now on the purely economic issue, I find it exceedingly difficult to make up my mind. But at a deeper level, the level where Peel’s mind was working, an answer, and a conclusive answer, makes itself heard. English society is sustained by industry, by manufacture and export. But the political structure of England is territorial and therefore agricultural. So long as Protection subsists, the Landed Interest must be unpopular, and if the Landed Interest is unpopular the whole political structure is open to attack. But put industry and the land on the same footing, and then you will have removed a constant sense of injustice, a gnawing grievance, which being, in the nature of things, a grievance against the Constitution, might some day demand a violent evacuation. So Peel saw, and so it came about. Gladstone left on record a conversation with some Trade Unionists years later, “You are not, I think,” he said, “so much interested in electoral reform as you were when I was young.” “No,” they said, “when we got Free Trade we gave up agitation. We have perfect confidence in Parliament, and we spend our evenings in improving our minds.” Those words explain as well as anything can the great political calm of the mid-Victorian age. I was looking lately at some political posters of the halcyon days. One can almost see the candidates scratching their heads to find something to disagree about. This season of mild weather may be said to have lasted till the death of Palmerston in 1865. Then comes the second extension of the franchise, Disraeli’s reform; and the stage is set for the great political contest which opens with the Liberal victory of 1868, so emphatically reversed in 1874. And it is somewhere there that we might draw a tentative line of division between mid- and Late Victorian England. But at no point do we get a limit so clear as that of 1846, and the afternoon glides into evening by imperceptible graduations of temperature and light.

To the historian, these halcyon times are welcome because they give him leisure to look around and see what was happening in spheres beyond the range of political conflict. In those years the Victorian compromise between laissez-faire and state-intervention took effective shape. The old, obstinate, resistance to all legislative interference—whether with property or with parentage—was beginning to crack under pressure from many sides. First is physical recoil, a revolt of the senses against the conditions of life in which multitudes were living. Close against that is alarm, if nature had her revenge and pestilence broke out. Nearly associated is the aesthetic trend, the desire to arrest the encroaching ugliness of life, and this aesthetic is inevitably of a Gothic, or feudal, cast. The Middle Ages were coming to be viewed not as a pageant but as a great social achievement, and when Kingsley and his friends propounded their doctrine of Associated Labour, the Edinburgh Review at once and correctly diagnosed it as a return to the Medieval Guilds. This in turn blends with the religious impulse, or if religion does not enter, the pure humanitarian impulse to do good. Finally, there is the scientific craving to understand, to trace effects to their causes, and this is linked with the administrative, one might say, managerial, drive to set things, and people too, in order. And then from the other side of the hedge you hear the dying growl—“Centralization, Sir. Never with my consent. Not English.”

It is not uninteresting to run through the list of social reformers and see in what proportion these tendencies are blended in their several characters. Shaftesbury—religious humanitarian, Kingsley—religious scientific, Morris— artistic managerial. But they run in and out in a way most characteristic of a time of intense curiosity not yet specialized, wonderful receptiveness, and untiring energy. For example: One of the great mid-Victorian names is Arthur Hassall, and the particular dragon he went forth to slay was the adulteration of food. Reading his reports you may wonder how the mid-Victorian kept alive at all. In 1851 Customs and Excise reported to the Treasury that there were no scientific means of distinguishing coffee from chicory. “Nonsense,” said Hassall, “the grains are quite different. So, call on the owners of microscopes to examine their coffee and report to the Exciseman. And,” he adds, “I notice from the advertisements that two new microscopes for amateurs have lately been put on the market.” He takes it for granted that there is enough scientific curiosity in the country for the Government to get its research done by private enterprise. I should guess he was right. The boy born in 1825 was very likely a sound naturalist, which meant that having read Vestiges of Creation and In Memoriam he was ready for the Origin of Species, ready to substitute Evolution for Progress, and to accept the consequences, even if those consequences meant the abandonment of his traditional faith. Judged by European or World standards, the doctrine of Natural Selection is the great achievement of mid-Victorian thought. And its significance lay in this—that it offered a new cosmogony. If Darwin did not go back to the Creative fiat, he had gone far enough to make it difficult for his age to retain the action of a transcendant, governing, interposing, Providence. The Theory of Evolution extended the sovereignty of natural law farther than any man had ventured before and thereby raised problems which went to the root of our ancestral ethics and even our politics.

Politically and socially, the fundamental assumption of Early Victorian thought is that the ideal to be aimed at is the community of respectable families grounded on a basis of competition and self-help, the State interfering only to remove obstacles, and any passing defects being remedied by charity. By 1850 or so we had moved some steps forward. The competition must not be wholly uncontrolled: the self-help must not be wholly unaided by the State. Certain standards must be enforced, certain facilities must be provided, and the propensity of everyman to better his position will do the rest. Our welfare, and our future, are in our own hands.

But is our future in our own hands? And the Darwinian thesis seemed to show that it was not. The compromise had dealt, more or less satisfactorily, with environment. It could not touch heredity. Perfectibility, the doctrine of the French Revolution and its sympathizers, had been confuted, it was supposed, by Malthus. It was by reflection on Malthus that Darwin arrived at his great generalization— that certain differences of bodily or mental structure would give one stock an advantage over another in the struggle for existence. And what else did Sir Charles Dilke—a radical and a republican—mean when he wrote, “The Anglo-Saxons are an exterminating race? ” If you regard Evolution as the dominant idea of the mid-Victorian epoch, I think you are bound to regard Imperialism as being, in no small degree, its embodiment in Late Victorian England.

Apply the Darwinian analysis to the population at home. Undeniably certain individuals have differential advantages—even certain groups. If you neutralize those advantages, say, by a rapid extension of the franchise, then you are artificially encouraging the ascendancy of a lower stock. Hence, Coventry Patmore’s Ode on 1867 when, according to the poet, the middle and upper classes and the final destruction of the liberties of England made inevitable:

In the year of the great crime,

When the false English nobles and their Jew,

By God demented, slew

The trust they stood thrice pledged to keep from harm.

That is mid-Victorian Conservatism up and roaring. And the answer? That there is still a great reserve of capacity to draw on, if only the grosser inequalities of education are removed, and unless we do draw on it we shall find ourselves slipping back in the struggle for national survival. It is always a good rule to ask of any period—what were people most afraid of? The fear of pestilence had gone, and the fear of subversion. In their place was the fear that in a competitive world we were not holding our own. We must, Forster said in 1870, make up for the smallness of our members by increasing the intellectual force of the individual.

If we generalize that dictum, if for intellectual force we substitute Quality of Life, we touch upon the problem which the mid-Victorian age handed on to its successor. Materially, mid-Victorian England was an unchallenged success. We had done what we had set out to do and what at times might have seemed impossible, to maintain our increasing population at a reasonable level of comfort, and in doing it we had, as it were by the way, created a great wealth of literature and science: great possibilities of enjoyment for all who wrote, “a degree of general contentment to which neither we nor any other nation we know of ever attained before.” But no age can solve all its problems and as we move along the decades, we are aware of what I have called the ambivalence. We could not help being proud, and yet there was much of which we could not help being ashamed. There was that vast untouchable world of casual labour. There were the thousands and ten thousands of children running loose in the streets. There were the 25,000 tramps on the pad. There was the mean, narrow, conventional life of the middle classes: the casual, hand-to-mouth government of the upper classes. And so the age of general contentment in an age of keen, and, at times, fierce criticism: by Dickens in Hard Times, by Tennyson in Maud; more gravely but not less potently by George Eliot: most eloquently by Ruskin: most profoundly and subtly perhaps by Meredith: Beauchamp's Career, I should judge, is the most penetrating critique of the Victorian patriciate ever written. And, if we remember that Self Help and Richard Feverel appeared together, that Great Expectations and Unto this Last followed them in the succeeding year, we may realize how vast and various is the mid-Victorian theme, and that a revolution is not the less a revolution because it is conducted under traditional, and constitutional forms.