The Matter of Scotland

Eric Linklater describes the odyssey of Scotland's national story in lyrical and poetic terms.

In an essay on Sir Walter Scott, Mr. G.M. Young brings into the same paragraph a reference to the historic value of Homeric poetry, and an appreciation of the like quality in Scott’s own verses. It was a discovery of this juxtaposition of the two names, by so learned and judicious an historian as Mr. Young, that gave me courage, at first to review, and then to enlarge, and now to utter in public, a rash statement I had made, not long before, to a few friends, warmly critical of it, in that warm and generous hour before midnight when imagination so often triumphs over fact and sometimes breaks through familiar darkness. There had been some talk of the usual kind about Scott, about his prolixity, his dull meanderings and his duller heroes, and I, not so much defending as stating a fine case for him, had declared he was Scotland’s Homer; and his place in history, I went on to say, was singularly happy because the story of Scotland, before him, was no more than a pre-Homeric tale.

Now conscience, as many of us know, has a habit of waking early in the morning to remind us, in disapproving tones, of all last night’s extravagance; and when, on a doubtful pillow, I first thought of my bold elucidation, not only of Sir Walter’s significance, but of so much Scottish history, I was inclined to put it away with other embarrassing memories, and forget it. But it would not, I found, lie quiet and be forgotten. It kept re-appearing, unexpectedly, like Mr. Punch or someone to whom one owes money; and in a mood almost of irritation I began to read—not methodically, as a scholar would, but amateurishly picking here and there—such history books as I had on my shelves, from Hector Boece in black letter, and Maitland’s massive volumes, through the laboured exegetics of the nineteenth century, to the livelier and more personal, more detailed and probably more reliable narratives of recent years. I read again Scott’s Tales of a Grandfather; and gradually I took heart, and began to think there was some truth in my assertion.

I am explaining the growth of my thesis because, as I hinted, I am not a scholar; and in these serious times the amateur must make his due apology. But having apologized, I propose to defend the amateur status, and my opinion, by a consideration of some commonly accepted facts and familiar figures in the privileged freedom of one who, with no professional concern for historical explanation, has none the less a natural interest in the buried centuries and the men who endured them; for man is cleverer than the amoeba in his ability to change his shape according to time and circumstance. And in the first place, with all possible brevity, let me defend my claim that Sir Walter was Scotland’s Homer.

I do not propose to argue the poetic equality of The Lay of the Last Minstrel and the Iliad. Sir Walter, the lame man, is not as good a poet as Homer, the blind man. But Sir Walter was equally devoted to the heroic past of his own country, and comparably inspired by its high-spirited legend, he prepared himself for a literary career by collecting with fervour, and editing with ingenuity, the rhyming tales of the Border minstrels, and the best work of his maturity was romantic narrative of the years between the Reformation and the ultimate defeat of the Highland clans—the last chapters, that is, of the pre-Homeric tale. His poetry, in Bagehot’s description, which Mr. Young conveniently quotes, was “a sensible thing; dealing with incidents which have a form and a body and a prosaic consistence”; and such, also, was much Homeric poetry. In his Tales of a Grandfather, manifestly a work of love but intended as a work of instruction, he wrote of Scotland as a minor Homer might have written of his own and neighbouring lands: of lands whose fortune was dominated, not by economic circumstance and constitutional amendment, but by inordinate valour and the outrageous quiddities of Hectors and Black Douglases; by a temperamental Achilles and Stewarts doomed by their genius and their birth; by the passionate gods of Olympus and the thundering sermons of a church built on predestination. Give Greece its proper supremacy in intellect and the arts—Scotland, alas, cannot parade a Pheidias or a Plato, an Aristophanes or Aristotle—but on our own ground, upon our modest level of the classical periphery, Sir Walter is Scotland’s Homer, equal in function if not in virtue.

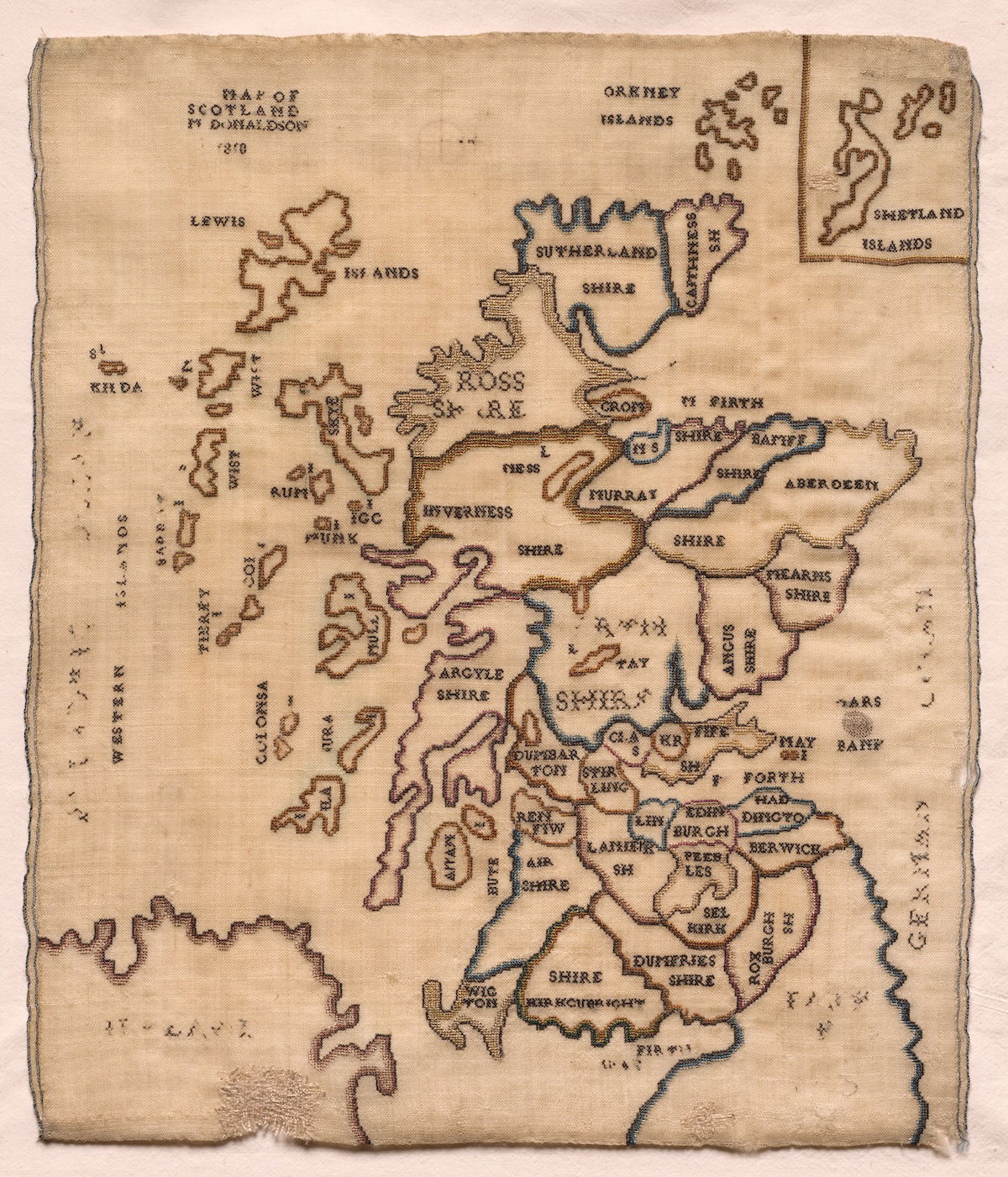

And now, that being granted, we must consider the more tendentious and, it may be, the more important part of my assertion: that the story of Scotland, in the five centuries before Sir Walter, cannot realistically, or indeed with any satisfaction, be considered as history in the modern sense of corporate growth and national development; but should be regarded as a pre-Homeric tale of remarkable men and the actions and re-actions which they provoked. I reserve, for a later mention, the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, which seem to be substantially different from those that followed; until, in the eighteenth century, a dominating instinct of that early period was re-discovered and re-employed.

In 1290 the Maid of Norway died, the heir of Alexander III, whose reign is traditionally the culminating epoch of a Golden Age of relative peace and obvious prosperity; and when the Maid was dead a hungry crew of claimants to the Throne submitted their titles, and resigned their independence, to the arbitration of Edward I of England. Edward demanded too much, and the heroic, anarchic, pre-Homeric tale began. Wallace and Andrew of Moray roused an indignant people to war against the English king, and the submission of their betters; and Robert the Bruce, a Norman Scot, inherited what they had fought for and his own genius had consummated. In 1320 the Parliament of Scotland, at Arbroath, made its memorable declaration of independence, denying equally the domination of England and the arbitrary power of its own monarch; and this document requires not only reverent but critical attention. “So long as there shall remain but one hundred of us alive,” said the Parliament, “we will never give consent to subject ourselves to the dominion of the English. It is liberty alone that we fight and contend for, which no honest man will lose but with his life.” And equally, said the Parliament, shall we resist the King, should he endeavour to bring us under English rule, and “immediately expel him as our enemy”. It is a truly heroic statement, in the first part quoted: heroic, not statesmanlike—for no statesman would protest that “liberty alone” was his aim, nor take his last hundred men into battle for it. But in the second part, in its truculent confrontation of the King, the parliament of Arbroath clearly threatens the lordly anarchy that did in fact succeed the death of Robert Bruce. Now anarchy is usually bred of desperation, and in 1320 the state of Scotland, despite its victory in war, was unhappy. The port of Berwick, the wealthiest town in the country—Berwick, where the Flemish trade came in—had been destroyed by the first Edward, and the fertile valleys of the eastern border lay waste, or blackened by fire. For five or six years, I imagine, Scotland had been living largely on the plunder and the ransoms taken at Bannockburn; and now, behind the heroic voices of Arbroath, one can see in the shadow gaunt, faces and the taut arrogance of men who are still gambling with a malignant, over-matching fate. A few years later Edward III renewed the war that his grandfather had begun, and the growing fields of Lothian were rained in a devastating campaign called the Burnt Candlemas. The House of Stewart succeeded to the Scottish throne, and its first two kings were a pair of elderly gentlemen of dignified appearance and lamentable incompetence. Robert III was so unhappy as to recognize his insufficiency. The House of Stewart was descended from a younger branch of the Fitzalans, a Norman family domiciled in Shropshire; and though the Stewarts bred gallant sons, and monarchs of errant genius, their fate, as kings, was dark and empty as that of another Shropshire lad, whom Housman mourned:

“In all the endless road you tread, There’s nothing but the night.”

James I, for trying to rule like Scotland’s necessary king, was murdered by his nobles; and James III was murdered by their sons because, it may be, he took kingship too lightly and preferred a music-master’s company to nobility. James II, in consequence of his immoderate interest in ballistics, was killed by the bursting of a gun; and James IV, for confusing chivalry with tactics, was killed, in company with many of his subjects, by the English. James V, after the shameful defeat at Solway Moss, died in anguish of spirit; and his daughter died in prison under the headman’s axe. James VI went to England and grew rich; but his son died, as his grandmother had died, on the scaffold. Charles II, worldly-wise, lived out his life, but his brother James, royally foolish, was driven from his throne and from his country. It is a sombre, miserable tale, and doubly miserable because the Stewarts were, by the title of their own minds, as lively, talented, brave, and charming a royal race as Europe has ever known; but the darkness of the family chronicle lacks the inspiring gloom of tragedy, because there is too much of it. It is melodrama rather than tragedy, because disaster comes so often from without, and lacks, in a moral or aesthetic sense, a proper motive. The fatality of the royal Stewarts was determined, not only by a certain incoherence in their own characters, but by a deadly incoherence in the land they tried to rule. For Scotland had no wish to be ruled by anyone, and submitted to the king’s rule only when it served the barons’ pleasure or their purpose; or in such periods as found the elements of dissidence exhausted, or balanced in mutual ill-will.

It is worth the observation that Scotland has very rarely suffered from the consciousness of military defeat. Of having been cheated, yes. Of being betrayed, entrapped, and bamboozled: why, certainly. When historic memory lapses into sentiment, or the last glass is re-distilled in tears, we are bitterly convinced that we have been robbed of our birthright, sold down the river, and our innocence, miraculously renewing itself, has been debauched again and yet again. But defeated in battle—never! Or hardly ever. The history books tell a different story, of course: they recite a tedious, melancholy tale of failure in arms at Halidon Hill and Homildon Hill and Neville’s Cross, at Berwick more than once, at Flodden and Solway Moss and Pinkie by the Firth of Forth, of the burning of the Border abbeys and of Edinburgh itself, of Presbyterian defeat at Dunbar and Jacobite disaster at Culloden. But the history books, with their literal account of what happened on such-and-such a day, are in this matter poorer witnesses to the truth than the ordinary man who relies on a mental sensation of events, and what, remains in his memory. For these battles, with two or three exceptions, were not national defeats, but the discomfiture and humiliation of certain factions or local assemblies who were in arms for a transient purpose which had happened to excite, simultaneously, the royal interest and that of a sufficient number of territorial magnates. It would be foolish to suppose that all these defeats were mourned, or even deplored, in every county of Scotland. It is far more likely that news of them, in many parts, was received with a neighbourly satisfaction. I remember, during the late war, disembarking from a troopship at Gourock on the morning after Greenock had suffered a heavy air-raid; and a railway-porter at Gourock, who told me about it, showed no sympathy for the country’s common loss, but rather a grim yet lively pleasure in the misfortune that had stricken, not him, but the man next door. And in like manner, I suppose, there were Highlanders who shook their heads but warmed their hearts at the news of Edinburgh’s burning; while many a sturdy, common-sensible Whig heard with glad relief the verdict at Culloden. Scotland, as a whole, was not infected by the malady of defeat after these battles because Scotland, as a whole, was not concerned in them. Scotland, indeed, was not whole, and the persistent attempts of the royal Stewarts to impose a rule of law were frustrated by a deliberate, and perhaps philosophical, resistance to a centralized authority.

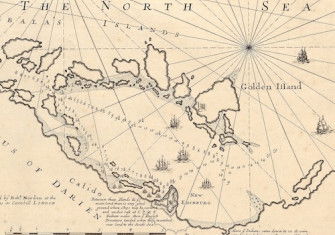

There is, moreover, a peculiar irony in the discovery that while badly led, poorly equipped, and undisciplined Scottish armies at home were suffering recurrent defeat, Scottish soldiers abroad were serving with distinction in continental armies, and making a profession of their native courage and aptitude in war. Seven thousand of them, in 1421, crossed over into France under the Earl of Buchan and defeated an English army at Bauge. True, they were nearly exterminated in a subsequent engagement, but from their remnants was formed the Scots Guards of France, whose regimental history was to endure for three hundred years. A century after Bauge, Christian II of Denmark had a thousand Highlanders in his army, and Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, in the seventeenth century, had eighty Scotch colonels and lieutenant-colonels in his service: it was the Scots Brigade that led the advance in his great victory at Leipzig. Mackay’s Regiment served in the Low Countries from the sixteenth century to the early years of the nineteenth. Russia and Prussia employed Scottish mercenaries, some of whom rose to high rank, and the O’Neills of Ulster enlisted soldiers in the Hebrides. The mercenary soldier is, in some ways, a more rational and comprehensible being than the fierce voluntary who fights for king and country, or a moral cause; but that Scotland should export, over so long a period, so great a number of mercenaries, when persistently it lacked a sufficient frontier-guard against England, proves not only the absence of due command at the centre, but the want of anything like corporate responsibility round the periphery. The Parliament. of Arbroath had declared a fight for freedom; and its descendants insisted on freedom to fight under any flag they fancied.

The common division of Scotland into Highlands and Lowlands, incompatible entities, is probably misleading. In Robert the Bruce’s time the whole country came very near to a working unity—according to Orkney tradition, even the Norse earldom sent troops to Bannockburn—and by the end of the eighteenth century the Kirk of Scotland, succeeding where the Crown had failed, was preaching the same gospel and exercising the same authority from Carter Bar to the Butt of Lewis. In the intervening centuries, admittedly, there had been differences of opinion which grew deeper and wider and more bitter as king after king tried to pacify and rule the Highlands by force of arms. For this increasing division the Highlanders have usually been blamed, and Celtic savagery or Celtic waywardness has been held responsible for the alien temper of the north and west. But until quite recently the historians of Scotland were all Lowlanders, and a certain prejudice may have hidden from them a very plausible explanation of the schism. So far from being the aggressors, the everlasting rebels, the Highlanders may well have retired into their mountains, shocked and horrified at the savagery and rebellion and lack of discipline in the Lowlands; and resolved to preserve their kindlier way of life from the ferocious hands that made so continual a clatter of war in the southern parts of the country.

When at last the Highlanders came in force to Edinburgh, in 1745, the capital waited in a tremulous dismay for butchery and rape and pillage, and was properly astonished when the insurgent clans behaved in its streets with a gentle dignity. Two hundred years before, there had been a pitched battle in the High Street between the Douglases under the Earl of Angus, the young husband of James V’s widow, and the Hamiltons under the Earl of Arran. Several Border feuds were settled, or prolonged, by rough, untidy fighting beneath the excited windows of those tall houses; and during the reign of Mary, Queen of Scots, Edinburgh became indeed a stage for melodrama, with the nobles of the reformed kirk, the Lords of the Congregation, lurking in the darkness like the black-suited murderers in Verdi’s Macbeth; with a cellar full of gunpowder, and Bothwell blowing on the lighted match. It is pleasant indeed (for it shows a fine, fresh imagination) to think that Edinburgh, with such a history behind it, could still expect to be astonished by the ferocity of the Highlanders.

Queen Mary’s little span of life in the capital was inspired by a fortitude inherited with her name, and tormented by the opposition of a power, new-born in Scotland, that was destined to re-shape it. The Stewarts had a dynastic strength, a dynastic purpose, that kept them afloat through fearful tempests. They were determined to be kings, and to go on being kings; and the dynasty survived until Charles I, adding divine right to kingliness, over-burdened and sank the ship. It was their misfortune to have, among their subjects, men whose ambitions were also dynastic. The Douglases were descended from that pattern of medieval virtue, the good Sir James; and the elder branch of the family acquired a domain so vast, with riches greater than the king’s, that even the latitude of Scotland had no room for both. A young earl of Douglas and his brother were murdered by Crichton, a Chancellor of the kingdom, and twelve years later the eighth earl was assassinated by the sovereign himself, James II. A younger branch, succeeding to the earldom of Angus, displayed as voracious an appetite for power, and such a habit of intrigue with the Tudor monarchy of England that the later Douglases are like a family of fierce but diplomatic acrobats performing on a tight-rope stretched between the two thrones. But these powerful and gifted families were exceptional only in the magnitude of the disturbance they created; their motive and their purpose were common enough, for as resolutely and habitually as in China, the interests of family were everywhere preferred to the interests of the state.

Certainly we shall save ourselves a good deal of pain and bewilderment by giving up attempts to construe the events of these centuries between Bannockburn and the Union of the Parliaments as formative and significant history. It is better for our comfort, and nearer the truth, to see them as Lord Seafield did when in 1707 he declared, “And there’s an end of an old song.” It had been indeed a brave and stirring song, full of violence and hardy beauty, and ringing with all the notes of energy. Regard it as such, and there is a constant pleasure in the brio and ebullience of the narrative, and a kind of magical unexpectedness, such as you find in great poetry, in many of the characters whose names make harsh music in it. Consider only a few of them, from the paladins of the War of Independence to James IV, a prince of the Renaissance with the iron chain of medieval remorse about his waist; and Mary, so vulnerable in a bitter world, so indomitable in purpose; and Montrose, his spirit translucent to honour, who served good sense with high enthusiasm and immortalized with his genius a little winter war in the mountains. Remember some of the lesser names: Black Agnes of Dunbar, mocking from her castle wall the besieging catapaults; the seaman, Andrew Barton; the cold brilliant mind of Maitland of Lethington; the poet Henryson; and some of the splendid, corrupt, and patriotic churchmen who walk so proudly in the pageant—yet prudently too, for did you jostle them in the crowd, you might feel beneath their priestly vestments the hard shape of armour. Think also of some of the wild events which these bold, unburdened men threw into the stream of time: the exploits of Douglas and Randolph in the war against Edward, as simply and heroically imaginative as the adventures of Odysseus; the Chancellor’s dinner-table with the black boar’s head upon it and the young king’s young enemies dead on the floor; the wild tournament of the clans on the North Inch at Perth; the fight at Otterburn, and Border forays when the ladies, in their high towers listening,

“About the dead hour of the night,

They heard the bridles ring.”

There, indeed, is a treasury from which an epic poem could be furnished—an Odyssey whose hero never found his way home—and there may well be as much ultimate value in the tale of men who would recognize no standard of measurement but themselves, as in the orderly account of a successful constitutional experiment.

I am well aware that I have said nothing, so far, of the Scottish parliament and its development; of the growth of Scots law; of Scottish commerce; and the early seeds that were planted of polite learning and general education. Good intention must indeed be acknowledged. But lawyers and parliament-men require more than scholarship and sagacity and good will; they are dependent on the co-operation of the people, and unless the people recognize, as a primary need, the need for government, their effort will be wasted. And in Scotland the need for government was not widely perceived. Of commerce, after the sack of Berwick, there was too little to have any decisive influence on the fashion of life; and of the apparatus of education there was too much. England had two universities, and could afford them; Scotland had four, and could not. The good impulse was divided, and spoiled of the effect it might have had if it had been concentrated in one place. In the conditions of the time there was, of course, much convenience m a local school, but one can scarcely avoid a suspicion that the foundation of the universities of Glasgow and Aberdeen and Edinburgh was prompted, as well as by natural piety, by a competitive spirit; by some desire to show St. Andrews that virtue was not confined to Fife. The War of Independence had bequeathed to bishops and schoolmen, as well as to barons and professional soldiers, a very sturdy conviction of their independence; it failed only to keep Scotland independent.

The church of Scotland—the Old Church, that is—had for long been richly endowed with prelates of great force of character; but by the sixteenth century its riches were chiefly material, and fantastic in their extent. The church owned nearly a half of the kingdom’s whole rental, and its corruption was fairly shown in Lindsay’s satire of The Three Estates. Its wealth excited the cupidity of the Scottish nobles; its corruption roused anger where it did not waken envy; the new Protestant party declared their intention of renouncing the congregation of Satan to establish the blessed word of God; and Elizabeth of England, averse to Catholic power behind her back, gave discreet assistance to the Reformers. John Knox came from Geneva, ready to play Lenin to Calvin’s Marx—as George Malcolm Thomson puts it—and the Reformation was effected with surprising ease and remarkable celerity. A Confession of Faith and Knox’s First Book of Discipline were published, and far away time may have flushed and trembled at the conception of a new Scotland. But gestation was to be long and difficult, and the date of its birth will be disputed. I myself incline to the belief that it was not born—this new land, which is our country of today—until the eighteenth century brought at last milder weather and a more reasonable climate. The years of its pregnancy were as tempest-born as the centuries of feudal strife.

In time the Reformation outlived the social, and economic, and political factors that had made it possible, and Presbytery, claiming the powers of a theocratic republic, grew pugnacious as the old nobility, and presently, following tradition, came into conflict with England. In the embarrassment of the Great Rebellion, with an anxious Cromwell at one end of the lists and a surprisingly placid King Charles at the other, the Scottish army acquired a political importance of which the Kirk of Scotland determined to take stern advantage. It gave the English Parliamentary forces an army of 20,000 men on condition that England should accept a Presbyterian government of its church; and the mirage of clerical uniformity was quickly obscured by the angry dust of another war. Mr. G.M. Young, whom I have already quoted, says that Presbytery failed in England because “in England there was historically no need for it, spiritually no room for it... . The transition from the Middle Ages had been conducted by a strong crown operating on a compact and law-abiding society”; and the English church, with a traditional liturgy, was in the hands of “a hierarchy which might with equal truth be regarded as an inheritance from Apostolic times or a branch of the Civil Service.” Reverse those statements, apply them to Scotland, and you will see why, or most of the reason why Presbytery did succeed in the north. In Scotland there was an historical need for it, and psychologically the room for it was furnished: the logic of Calvinism, and its intransigence, appealed to the Scots. Their society, moreover, had been neither compact nor law-abiding, and having begun to recognize the need for government, they were disposed to welcome it when it came to them from the pulpit, buttressed by the authority of God’s revealed word. But until the end of the seventeenth century, or near, it, there was still too much passion in the air, too much perplexity and bitterness—and in the towns and countryside too dire a poverty—for the growth of the Kirk’s strong government to come to life. It had to wait for secular assistance and a kindlier season. It had to wait until Scotland should drain its land, plant trees for shelter, and learn to grow grass.

The last years of the seventeenth century were sunless and drenched with rain and no crops ripened. Famine came early in the eighteenth century. The land was very subject to disaster because for centuries its fields had been barbarously misused, and agriculture had become witless and dispirited. The land lay bare, unsheltered, wind-swept; the soil was starved, and cattle starved; men ploughed the mountainsides because the valleys lay sour and water-logged. But not until the middle of the century could the improving lairds, handicapped by their own poverty and the opposition of the people, begin their task of repairing the enormous damage done by centuries of war and the pre-Homeric age. Then at last, however, the Lowlands began to assume their present appearance, and acquire a modern economy. The century was interrupted by two Jacobite rebellions, but of infinitely greater importance was the introduction of good grass-seed and clover, of turnips and potatoes. In the Lowlands trees were planted for shelter, and fields enclosed; in the Highlands vast forests began to cover the naked sides of the hills. The hideous desolation of the land put on a new beauty, and with beauty came new prosperity that swiftly ripened. The stem doctrines of the kirk were moderated, and the ministers, without losing their authority, won the general affection of their flocks. New industries were planted, and filled and grew as plumply as the innovating turnip. In a hundred years the beggar’s revenue of Scotland was multiplied fifty-fold.

By the end of the century a new country was in being that could hardly trace its relationship to the wild decades of the past. Sir Walter Scott was collecting the remnants of the Border minstrelsy with the care and reverence that are properly owed to the scanty relics of a vanished past. There was a lively, brilliant, and diverse intelligence abroad in the land, and now it was a formative intelligence. David Hume may have scuttled a creed, but Hume gave nourishment to intelligence itself; and when Adam Smith theorized on the wealth of nations, he discovered new sources of wealth. Where for centuries there had been little but destruction, there was now a comparable enthusiasm for building, and masons worked as they had never done since the thirteenth century and the death of Alexander III. In its constructive energy, indeed, the eighteenth century shows a curious resemblance to the closing ages of the Scotland which Kenneth Macalpine founded and Alexander III was the last to rule. Alexander’s kingdom—a Norman structure on Scottish soil, as England of the time was a Norman creation on a Saxon basement—appears to have had a logic, an organic growth, a constitutional development, which the later centuries never knew. The great Border abbeys are the evidence, in their grace and splendour, of an enviable, proud culture; and evidence too, when one considers their economic foundation, of a rich and civilized community. The Norman-Scottish kingdom of Alexander was a rival to the Norman-Saxon kingdom of Edward I, and its wealth and close cousinship were probably at the root of Edward’s insensate ambition to destroy it.

Now wealth was returning, and coming so rapidly and in such profusion to a country which knew little of its use, that new danger was bound to accompany it. Danger now not from without, but from within. Coal and iron and cotton mills and James Watt brought prosperity, and peril too. In the nineteenth century the Scots fell upon their prospect of wealth with the fury of pioneers attacking a virgin country of whose past they knew nothing and for whose future they cared no more. The Industrial Revolution created in the midst of wealth a squalid misery as evil as the destitution of internecine war and medieval famine; while in the northern Highlands, with a cold brutality, a virile but redundant peasantry was swept from its immemorial acres to make room for the sheep which, in a nobler landscape, were almost as profitable as the belching chimneys and lurid foundries of the south. A solitary remnant of the pre-Homeric age lived long enough to see this strange new world, and that was the Scottish tendency to excess: before the rage of industry the power of the Kirk failed, as the Crown had failed before the feudal rage of the barons. Politics began to invade the Kirk’s domain, and the voice of the Radical disputed the diminished teaching of Knox and Calvin. But Scotland survived the young fury of the industrialists as it had survived so much in the past, and entered the twentieth century disfigured, half-desolate in some parts but in others still rich with the endowments of the first founders of its new estate; and with sufficient energy, not only to survive two major wars, but to entertain ambitions for its future.

What is one to say of its present state, and what can one guess of the years to come? This, for a certainty: that the present looks far healthier, and the future should promise more, if we can clearly see ourselves as a young people, with only two and a half centuries of real history behind us; but underneath, in the miocene strata, an old song that was sung by brave, unprofitable voices, to a very stirring tune. Much has been made, and much won, in two hundred and fifty years; and if much has been botched and spoilt, there is some excuse in our knowledge that the foundations were broken ground. The Kirk and the good sense of the eighteenth century, on which Scotland of today was built, built sturdily and well; but deeper down, in the eocene clay of the story, are the great abbeys of Alexander’s vanished kingdom, and in their ruins beauty has survived. It is the only legacy of our ancient history, and those who build our future, whatever virtue or duty may inspire them, will, I hope, desire to be as graciously remembered.