Charles the First and Rubens

Michael Jaffe traces the relationship between king and master.

At the age of twenty-three, Charles, Prince of Wales, possessed a self-portrait by Rubens. Rubens was then forty-six. He had not designed, nor was he to design, any other portrait of himself for a prince. In 1623, when Charles asked him for his own picture, he had finished the big series of Bible stories for the ceiling of the Jesuit Church in Antwerp, and was engaged on the political allegories commissioned by Marie de Medici for the walls of the Luxembourg. These two cycles of decoration established him as the most brilliant and successful painter outside Italy. The portrait that he sent to Charles, with protestations of unworthiness, was not intended solely as a dazzling bid for the important commission that the Stuarts had to offer, the decoration of the Banqueting House ceiling. It was a gracious and genuine tribute to the young man of whom he had written to Valavez, “M. le Prince des Galles est le prince le plus amateur de la peinture qui soit au monde.”

The Banqueting House, which Charles’ father had commissioned from Inigo Jones, was nearly enough complete to be used for the St. George’s Day Feast of 1623. Almost from the day of its foundation, it had been a building famous in Northern Europe. Rubens knew of it from Carleton, our envoy at The Hague, or from Gerbier at Brussels; and certainly in detail from Van Dyck, who visited England in the winter of 1620-21. In September, 1621, he wrote to Carleton’s agent for buying pictures, in Brussels:

“As to His Majesty and H.R.H. the Prince of Wales, I shall always be pleased to receive the honour of their commands, and with respect to the Hall in the New Palace, I confess myself to be, by natural instinct, better fitted to execute works of large size than little curiosities. Each one according to his gifts: my endowments are such that I have never lacked courage to undertake any design, however vast in size or diverse in subject.”

Immediate advantage was not taken of his offer to paint the Whitehall Ceiling. James I had engaged Inigo Jones in 1619 because he recognized in him, if not the force of genius, a weight of Classical learning conversable with his own. He could therefore trust the plain evidence of his eyes that Jones had designed a building as beautiful as a classically-inspired work should be, one more than worthy of the masques which it was to house. To employ an expensive and possibly unreliable painter to decorate the ceiling was, however, beyond his caution; although Prince Henry, had he lived, could have vouched as a fellow antiquary for the immense learning of Rubens.

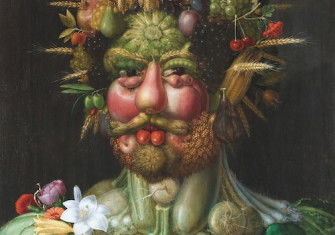

Rubens, it may be seen in his self-portrait, besides the grace of learning, loved pleasure, pomp, procession, and all that makes up masque. To please the English taste, the learned Jones had travelled in the Italy of Palladio and Parigi; the learned Jonson in the realms of gold. The splendid series of entertainments they devised were, to James, not so much recreation for the eye, as intellectual treats such as Scotland had not afforded him. The life-size emblems which the Jacobean masque employed were not to him groups of figures, or movement, or colour, or scene, but a style of thought.

Charles, by distinction, found masquing nights an education in visual beauty that prepared him to discuss, eight years later, a vast allegorical decoration with Rubens. His education in great painting came from his visit to Spain with Buckingham and Gerbier in 1623. England had then few pictures grander than a full-size portrait. Henry VIII had left the Royal Collection with the Holbein “Noli me tangere” and the Mabuse “Adam and Eve” [both at Hampton Court]. The Somerset-Arundel Collection included about a dozen minor Venetian pictures, hopefully labelled Tintoretto or Veronese or, in the case of “Venus, very rare,” Titian. Their standard was that of Bonifazio or Schiavone. Danvers and other private collectors held nothing more notable. Isaac Oliver painted histories “in great”; but none survives to reveal their quality. There was certainly nothing to compare with the Spanish Royal Collection, whose glory was seventy works by Titian; “the Pardo Venus”, the portraits, and the “Gloria” for Charles V; all the poesie for Philip II, more royal portraits, and both the late self-portrait and the late “Entombment”. Rubens first saw these marvels in 1603, at the age of twenty-six; and he was able to return to their inspiration again and again. Charles had less than four months to absorb the supreme experience of painting that Western Europe had to offer, before the vain quarrel between Buckingham and Olivarez made the continued stay of their droll embassy in Madrid positively dangerous. The party returned to England with Charles determined to be not only a collector of pictures, but, like the Habsburgs, the patron of a great painter.

While they were in Spain, attempting to woo the almost unapproachable Infanta, the court-painter of Christian IV of Denmark, Franz Cleyn, arrived in England at James’s invitation. James had heard, through his wife or his father-in-law, of the histories painted by Cleyn to decorate the royal palaces of Christiansborg and Frederiksborg. Cleyn had spent more than four years in Italy. On his return to Denmark, he had painted, provincial imitations of Veronese and Tintoretto. James thought him suitable to design new cartoons for his tapestry works at Mortlake. Cleyn was employed also in the Double Cube Room at Wilton, and on decorations for Somerset House, Carew House, and Holland House. Before Charles came back, Cleyn, or de Critz who worked in the Single Cube at Wilton, might conceivably have got the commission for the Banqueting House. Their charges were not exaggerated, and they were available in England. After October 1623, the contract was not open to third-rate talent.

Two other painters, beside the greatest living, may have been considered; Orazio Gentileschi and Gerard Honthorst, the pupil of Bloemart. In the year following his accession, Charles invited Gentileschi to London. He had then worked with success for the Republic of Genoa, for Henrietta Maria’s cousins in Tuscany, for the House of Savoy, and for Marie de Medici in France. Charles and Buckingham regarded him highly: he was granted an annuity of £100; and a house was furnished for him by royal command, at an estimated cost of more than £4,000, a thousand pounds more than was paid in 1638 to Rubens for his canvases at Whitehall, three years after their delivery. Gentileschi in return painted nine large religious subjects [now in the Hall of Marlborough House]; also decorations at York House, and ceilings at Greenwich, by which Charles might judge his suitability for the Whitehall commission.

He was capable of the task. Moreover, in 1626, there seemed little likelihood of bringing Rubens to London, since the disaster of our Cadiz Expedition made peace with Spain a remoter prospect than ever. Buckingham’s folly and his influence with Charles kept England at war. While there was war, Rubens was especially busy in the service of our reluctant enemy, the widowed Infanta Isabella, in whose regency of the Spanish Netherlands he had been since 1621 the trusted adviser in all affairs. Yet Gentileschi returned to Italy without a contract.

How seriously Charles then considered Honthorst is hard to tell. He had been sufficiently impressed by his “Aeneas flying from the Sack of Troy” to encourage him to visit London in 1628. Here Honthorst painted a huge allegorical piece [on the Queen’s staircase at Hampton Court]: “Apollo”, Charles, perched with “Diana”, Henrietta Maria, on Olympian clouds, bends graciously to welcome “Mercury”, Buckingham, who leads on the earthbound troupe of “Liberal Arts”, Court ladies. Charles may have been tickled by this fanciful masquerade. He rewarded Honthorst well. He did not seek to employ him at Whitehall. He was sure enough what he wanted, and whom he wanted, to be prepared to wait.

The work of Rubens was now well known to Charles. In April, 1625, Buckingham had gone to Paris to complete the arrangements for Charles’s marriage to Henrietta Maria. There he had met Rubens, who was finishing and supervising the hanging of the Medici cycle. Rubens drew him, and painted his portrait as a cavalier [at Osterley Park], Five months later, Buckingham was in Antwerp, with Carlisle and Carleton, to negotiate a peace with the United Provinces; and he was shown the princely collection of painting, sculpture, and antiques, that Rubens had formed. This collection, after many persuasions, he succeeded in buying. It included thirteen important pictures by Rubens himself, besides notable Italian works. They made, with the equestrian portrait and with the flamboyant ceiling decoration, “The Apotheosis of Buckingham” [at Osterley Park], that Rubens also painted for him, a rich filling for York House; and one that Rubens hoped might be of some diplomatic value to soothe his touchy pride. Moreover, Charles himself had bought from the young Duke of Mantua in 1627 his family pictures, which had been the study of Rubens, and to which Rubens had added in his early days as court-painter to the Gonzagas. It was said after this famous sale that the Mantuans would immediately have subscribed double the money to regain their historic treasures.

The opportunity to employ Rubens arrived unexpectedly. The glorification of Buckingham in the “Apotheosis” was followed in three years by “the obscure catastrophe of that great man”. Buckingham was assassinated, and the real obstacle to peace between England and France was removed. Although Buckingham had come round to the idea of peace with Spain, and had himself written, in April, 1628, urging that Rubens should visit that country to mediate on behalf of the Infanta Isabella, a reliable peace could not have been hoped for, while both he and Olivarez lived to influence their Kings.

Rubens actually left for Madrid just before Felton stabbed Buckingham and La Rochelle surrendered. His reactions to those events, and the reactions of the Court of Philip IV, may seem slow by modern standards, and conversing and painting with Velasquez to have occupied more of his time and inclination than diplomatic business. In fact, not only was Spanish diplomacy all stiff delays and proud gravity, but Rubens’ position as a diplomat was invidious; and it remained so even after Philip IV had made him Secretary of his Privy Council of the Netherlands and a grandee.

Leaving Spain on the 27th April, he travelled across France as fast as he dared without attracting the suspicions of Richelieu, to report to the Infanta in Brussels. After a brief visit to his own home in Antwerp, he arrived at Dunkirk only one month after his departure from Madrid. There, with his brother-in-law Brant, he awaited the safe conveyance of an English ship.

He came to England, not as plenipotentiary from Philip IV to arrange a treaty, but as the envoy of the Infanta Isabella, to negotiate his own “Proposition of a suspension of armes”. To the fury of the French, he succeeded in this immediate object; but the formal exchange of ambassadors between ourselves and Spain was not completed until Don Carlos de Colonna had audience in the Banqueting House on the 6th January, 1630; and the Treaty of Madrid was not signed until the November following.

During the nine months of his stay in England, Rubens lodged, at the King’s expense, with Gerbier, Buckingham’s one-time Master of the Horse. He was frequently with Charles, seeing collections, discussing painting, comparing the merits of his pupil Van Dyck with those of Velasquez, or planning the decoration for the Whitehall ceiling; and Charles loved to be painted. He knew the portraits that Rubens had done of Buckingham in Paris: he had the portrait of the young Francesco Gonzaga and the self-portrait in his Breakfast Room at Whitehall; he was well acquainted with the power of Rubens to make a picture of great beauty and, in doing so, to convey character and destiny in the likeness of a face. At the speed at which Rubens worked—his portrait of Van Dyck [at Windsor Castle] is one brilliant example—he could have done a fine portrait of Charles in a morning. By what strange understanding no portrait was made, we may never know. A wish to spare the feelings of the regular court-painter Mytens, or to leave the way clear for Van Dyck, is an incomplete explanation of a magnificent opportunity missed.

“The Landscape with St. George”, which Rubens painted in England to take home with him “as a monument of his abode and employment here”, suggests a missing part of the truth. Charles knew of this lovely picture, but he was only able to acquire it later in Antwerp through an agent. No more literal than any other landscape by Rubens, it is a view, as from an upper window, across St. George’s Fields, near Lambeth Marsh. The background is composed of sights familiar to Rubens during his stay at Gerbier’s home on the York House Estate; St. Mary Overy, Lambeth, and the Banqueting House itself. The elements of the foreground are stranger. There are two principal actors, a fallen monster, attendant figures and spectators. They have about them the sad and stately beauty of the fading moment in the masque. The Princess stands revealed as Queen Henrietta Maria; the Patron Saint in armour is the King. The set of his figure is separated by a world of comprehension from the standing, full-length portrait painted the year before by Mytens [at Hamstead Marshall]; and from the equestrian portrait, in armour, by Van Dyck to come [sketch at Windsor Castle], By the light of a late evening sky, he appears already as the tired Knight of the Civil Wars. To suggest that Rubens caught an inkling of that future from his days with the King, is not to imply that he foresaw Marston Moor and Naseby; only that he might not have wished to paint that uneasy half-knowledge into a full-size portrait for a peculiarly sensitive and understanding sitter.

This poetic view of London, her river, and her fields is the one landscape of England that Rubens made. After ten years of war in Europe, visitors to England were soothed by her remoteness from the real horrors of that conflict. War for the English, once it was clear that the threat of the Armada would not recur, meant romantic enlistment in the service of Gustavus Adolphus, or, after a shortlived burst of enthusiasm for fighting Spain again, unromantic pressing into one of Buckingham’s bombastic expeditions: it meant taxes at home, and foreign privateers on the trade-routes; but their countryside was untouched.

Rubens saw at Whitehall the little Raphael of “St. George” [in the Louvre], that perfect compliment carried by Baldassare Castiglione from Urbino to Henry VII, and recovered for the Royal Collection by Charles I. Raphael painted the Saint mounted, fully armed, with the Garter about his knee, in the act of striking; and he decorated the background with a still and gentle landscape of Umbria, so to transform a scene of violence into an idyll. The Rubens landscape stands at a great distance from this, in time, in painting, and in feeling. It is too poignant for a compliment or a present. In spirit, as in finished splendour, it goes beyond his own “Tourney before a Castle” [in the Louvre], an entrancing late work of pure romantic fancy, into the realm of the imagination.

His present to the King was “War and Peace” [in the National Gallery], While “The Landscape with St. George” expressed private feelings, this sumptuous “picture of an Emblem wherein the differences and ensuences between peace and war is showed” celebrated diplomatic success in the grand, public manner. Also, since Madame Gerbier was the model for “Peace”, and since the children are her children, it paid a courtesy to his hosts. It was hung in the Bear Gallery at Whitehall, for all the Court to admire the painted beauty of flesh and silks against the grisly horror of the hag of war.

The emblematic idea of “War and Peace” is very simple; the subtlety lies in the painting. Equally the set of ideas for the Banqueting House ceiling, the programme agreed in conversation between Rubens and the King, is of heroic simplicity: Chastity triumphs over Lust; Peace embraces Plenty; Britannia perfects the Union between the Crowns of England and Scotland. Only the relation of the figures, the play of their limbs, and the rush of their draperies are complex. To suppose Rubens ignorant of English history, unaware that James’s reign ended, as it had begun, with England at war against Spain, or that he ignored events to pay a spectacular, tongue-in-cheek, compliment to the Stuart dynasty, is as absurd as to assume that his portrait of Buckingham on horseback, prancing amongst naked and luscious nereids, is an intellectual sneer at a flashy favourite. To suggest that the King was a man like his father, with a learned, literary interest in the Divine Right of Kings; or that he had an upstart, or Papal, sense of the important role for painted decoration in dynastic propaganda at Court, shows a corresponding misreading of character. The grand Roman ceiling which Pietro da Cortona frescoed for Urban VIII in 1632, glorifies not only the Barbarini family but the Barbarini Pope; and, through him, the triumphant Papacy. Compared with that overwhelming and revolutionary achievement in decoration, the Whitehall ceiling, divided by coffering in the Venetian way, is old-fashioned. Indeed, its paucity of Classical allusion would hardly have satisfied the pedantic James.

“The Apotheosis” was most likely suggested by Rubens. The idea derives from paintings of the Assumption, a theme which, in the art of Rubens, goes back to his painting of 1614, in the Jesuit Church of Antwerp, and forward to the sketch of the late sixteen-thirties. It is a central one in all baroque art. The requisite galaxy of rising and twisting figures, held dramatically by a single emotional idea expressed in one figure, is superlatively suited to the decoration of a ceiling. Rubens had already adapted the theme to secular purposes in the Medici cycle, and in the closely related “Apotheosis of Buckingham.”

“The Government of James I”, in the south rectangle, also adapts an idea used previously by Rubens, in the “Government of Marie de Medici”, whereas the idea for the large canvas as the north end must be the King’s own pious tribute to the memory of his father’s frequently expressed pride in “The perfection of the Union between England and Scotland”, the result of his having had heirs male at his accession to the English throne in 1603.

To paint this idea of the King, Rubens used an earlier motive taken from his “Esther before Ahasuerus” in the Jesuit Church in Antwerp. That panel is itself based on his recollection of Veronese’s ceiling, showing King Ahasuerus, in the Church of San Sebastiano in Venice. This and other churches Rubens had seen as a young man nearly thirty years before, when he spent his weekends from Mantua studying painting and architecture in Venice and Parma. Similarly, the guardsman on the steps of James’ throne is another recollection of North Italy; his posture is reversed from a drawing Rubens made after Corregio.

Although in the three main fields of the finished work the master’s own hand is much and magnificently in evidence, his painted sketches give the clearest idea of his intentions: this, primarily, because Rubens was the first artist to clarify his ideas for a large composition by painting sketches instead of making drawings; secondly, and incidentally to this commission, because Rubens in Antwerp miscalculated the English foot. When the canvases arrived in London in October, they had to be cut to fit the compartments; the effect on Rubens’ compositions is most noticeable in the excessively narrow ovals; and Lust, for example, has thereby lost her head as well as her reputation. Thirdly, in scaling up the architecture in the large rectangles, the lines of perspective have not been corrected, as Joseph Highmore noted with pedantic care a century later. The figures are foreshortened to suit eyes raised, in the comfortable and established Venetian manner, about forty five degrees from the horizontal plane. The pillars appear out of phase. Rubens died fifty years before Padre Pozzo published the secret of constructing an architectural illusion on ceilings, that was Jesuitically exact.

Rubens returned to the Infanta in Brussels with an English knighthood and a Cambridge degree. She sent him at once to Madrid to report the success of his mission. He had narrowly escaped drowning in the Thames on his way to Greenwich: from his return to the Netherlands until her death in November, 1633, he was more than once hard put to avoid total submergence in diplomacy. Work for England was held up by other commitments. He had previously undertaken a second cycle of decorations for Marie de Medici, the Henri IV series; work on these was only abandoned at her exile in 1631. The San Ildefonso Altarpiece, requiring his full personal attention, had to be finished in 1632. Elaborate models for the weavers had to be prepared for the nine great allegories in tapestry, showing “The Triumph of the Faith”, ordered by Philip IV for the Clarisses Convent near Madrid.

On the 1st of August, 1634, Gerbier wrote to Charles from Brussels “what ignorant spirits utter seing the great worke Sr Peter Rubens hath made for yr Majts Banqueting house, lye here, as if for want of money. Spaniards, French, and other nations talke of it, the more it’s said the matter to reach but to 3 or 4 thousand pounds”. In 1634, Charles was not short of money, and had only that year to levy Ship Money for the first time. Worries over safe transit, not payment, caused the delay. The order to despatch did not come until July, 1635; and the question of customs duty held up sailing another month. So certain work on the canvases was found necessary “in retouching and mending the cracks which had been caused through their having been rolled up almost a year”. Rubens desired to do this before shipment, “fearing, when past the seas, to be taken by the gout, of wch often visited”. For security from foreign interference the pictures were sent privately from Lyonel Wake, a merchant in Antwerp, to William Cockayn, a merchant in London, in October. After this “merchandise” had been set in the ceiling, there is no record of a masque being held in the Banqueting House. Charles feared not only the smoke from the torches, but fire. On 12th January, 1619, a candle falling among “some oily clothes of the device of the mask” had started a blaze which burnt his father’s first banqueting-house to the ground.

Four years after the Rubens paintings were placed, Charles, with the Scottish Wars upon him, really was short of money. Jordaens, and not Rubens, was approached through a third party about decorations for the Queen’s Chamber at Greenwich. Such furtive economy Gerbier regarded as madness in a patron; but his efforts to persuade Charles to employ Rubens again openly, if only for the ceiling-piece which needed foreshortenings, were in vain. On 31st May, 1640, Gerbier forwarded a letter from Rubens, sent the previous month. Rubens writes of a landscape by Verhulst, “finished according to the capacity of the master, under my direction”, which Charles wished to acquire. The subject was the Escorial and the surrounding country, with the Sierra Toccada in the background; “there is a tower and a house on one side though I do not remember their name particularly, but I know the King went there at times when hunting.” The picture was made after a sketch done by Rubens on his first visit to Spain. Some correspondence ran between Gerbier and England during March and April, questioning how Rubens should be paid and how much: but Rubens, as Gerbier at last realized, had not, from the King’s first profession of interest, desired payment. “Please God”, Rubens writes, “the extravagance of the Subject may give some recreation to his Majesty”. He himself was then engaged in the monster commission for Philip IV, the painting of one hundred and thirty-seven scenes from Ovid for the Torre della Parada, and desperately anxious to finish the work; an anxiety more agonizing since, for days at a time, his gouty fingers were unable to hold a brush. To his letter covering that of Rubens, Gerbier added, postscript: “Sr Peter Rubens is deadly sick; the Phisicians of this Towne being sent unto him for to trye their best skill on him.” The same evening gout reached his heart.

All that Charles possessed of his painting was catalogued nine years later as the chattels of the Commonwealth. In the King’s own catalogue stands this entry for his Cabinet at Whitehall:

“There hangs at the roof of the seeling above the Table don in oyle Cullors the Moddle or first paterne of the paintings wch is in the Banqueting House Roof wch was sent by Sr Peter Paule Rubin to yor Maty to know yor Mats approveing thereof.”

In this most private room, the model for the Whitehall ceiling kept company with the Leonardo “St. John the Baptist” and the Raphael “St. George”, the Giorgione “Shepherd with a Pipe” and the Titian “Lucrece”, with paintings by Mantegna and Holbein and Jan Breughel, the choicest small pictures of the royal collection, forming an essential part of his daily life.

Charles had to die for his steadfast refusal to make the distinction that the Parliamentarians demanded, between the private and public dimensions of kingship. During the eleven years of his rule without parliament, the Banqueting House, and the life which it contained, had been, the public emblem of autocracy. The regicides chose that site, and not the customary one on Tower Hill, or the one in Westminster used for Raleigh, as the appropriate place of execution.