Bristol

Bryan Little pays an architectural visit to the famous city on the Avon.

Bristol is England’s sixth provincial city, our largest city west of London or south of Birmingham, with almost half a million people against 200,000 in Plymouth, her nearest western rival; yet there have been moments during the last century and a half when she has strangely slipped out of public notice. The cities that have come to the forefront have been the new giants and heroes of the Industrial Revolution—Birmingham, Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield, Leeds; but by comparison with, say, Birmingham, Bristol can point to four times as long a period of civic eminence. Geography helps to explain the position she has occupied; for Bristow, or Bristol, means the “place of the bridge”; and it was as a river-crossing from Wessex into Mercia, not primarily as a port, that the Saxon settlement came into being. But it was as a port that she subsequently prospered. Here the Avon joins the Severn, not within the territory of one province but of two. Bristol is not too far up Channel to serve the south-west, nor is it too far down to be of use to the Severn basin, a crucial district in medieval England. Along the whole coast of the Bristol Channel no other harbour can be compared with hers. She is also so placed as to be a natural port for trade with Ireland and South Wales. While her hinterland was one of England’s richest areas, Bristol became an important centre and, for a few decades, the second town in the Kingdom.

1051 seems to be the earliest certain date in Bristol’s history; for in that year it was from the Avon that Harold fled to Ireland with one of his brothers, banished by Edward the Confessor in an opening move of the Saxon-Norman feud that culminated at Hastings. A few years later, restored to favour and in command of Edward’s troops, Harold again sailed from Bristol in an expedition against the Welsh, and two years after Hastings, Harold’s sons attempted a landing here in an effort to win back their father’s crown. Small wonder that William took care to secure so vital a point by founding a royal castle that was in time to become one of the strongest in the West.

During the reign of Stephen, the occupant of Bristol Castle was that now half-forgotten but towering figure, Earl Robert of Gloucester, natural son of Henry I, who had inherited it by marriage. He was the man who rebuilt the fortress with its great twelfth-century keep and who founded in Bristol the first of her monasteries. When he and the Empress Maud were the leaders of the party opposed to Stephen, they made Bristol their virtual capital and their one impregnably secure holding point, also their port for communications with the Empress’ territory in Anjou. Such was the reliance placed on Bristol by Earl Robert and his half-sister that they used the castle for a few months as the place of confinement for Stephen himself when they had him in their power.

The Angevin connection meant much to Bristol and the rest of Gloucestershire. Henry II and John are the monarchs to whom she owes the beginnings of her civic status; and it was Henry who buttressed her Irish commerce by giving his new conquest of Dublin to the men of Bristol for them to inhabit as something like a colony. Even in the deep adversity of his last days, John could depend on Bristol and its Severn hinterland as his most loyal base; and his young son, the boy king Henry III, had the same experience. The Severn basin was his one sure holding when his father died, and in Bristol Castle, a few days after his hasty crowning at Gloucester, he received his nobles’ allegiance and first reissued Magna Carta.

There were other occasions during the Middle Ages when Bristol proved her usefulness as a strategic key point. But on the whole her existence was placid—far more so than that of Southampton and other towns on the English Channel which were often ravaged by the French. Sooner than most of our medieval cities, she was able with confidence to spread her dwelling houses beyond her walls; by 1500 the castle was only nominally a fortress and private citizens had occupied the towers along the town walls. In 1373 Bristol, spread between Gloucestershire and Somerset, became a county in its own right, the first town outside London to attain what we now call “County Borough status”.

By now commerce was her main activity. There was the great carrying and distributing trade with other English towns and cities—with South Wales and the Western counties, and also with the Midlands and Marches by the Severn and Wye. Most of this traffic was by water, and continued to be water-borne till the coming of railways. Then there was Bristol the manufacturing town—of soap, from a date not later than about 1190, and increasingly of cloth for export. She also exploited, but not perhaps for industry, the coal supplies of the neighbouring forest of Kingswood. Lastly— and herein lay the wealth of the big men in the economy of Bristol—there was her ship-owning and her trading overseas. By comparison with London and the East Coast ports, a far higher proportion of Bristol’s merchanting was with Atlantic ports, with Ireland, Spain and Portugal, but above all with Gascony and especially with Bordeaux—cloth for the Gascons and wine for England from the Gironde. In spite of the interruptions caused by war, Bristol maintained a continuous contact with the Continent. Only in the sixteenth century do we find a change of emphasis as political vicissitudes and changes in the English palate shifted the wine-trade towards Spanish sack.

Late in the Middle Ages, probably at a date about 1475, we have the detailed picture of Bristol—uniquely detailed for any English town of the time—included in his “Itinery” by the writer William “of Worcester”. By then Bristol had the full complement of civic and social institutions. There were the guilds and religious fraternities, notably the Society of Merchant Venturers, which alone of Bristol’s companies has survived until the present day. There were numerous parish churches, the hospitals and charities in unusual numbers, the Friaries of all four orders, chapels such as that of the Assumption, a splendid fourteenth century building running athwart the house-lined Bristol Bridge, like so many other local features an accidental or deliberate copy of a London model. The population is hard to judge; but it may have been about 12,000, enough to put Bristol among the first three or four English medieval towns. In one respect alone, despite the outstanding beauty of her churches, was the Bristol of 1475 a little behind her neighbours. Her ecclesiastical standing had yet to match her wealth and civic dignity. For Bristol still looked for her bishop either to Worcester or to Bath and Wells; when at the Reformation there came to be a Bishop of Bristol, with his Cathedral in the architecturally notable eastern half of what had been St. Augustine’s Abbey; the See was so poorly endowed as to remain the Cinderella of English dioceses, a mitre but not a living. Nor in the Middle Ages did Bristol have a dominating monastery as did Bath or Gloucester. St. Augustine’s was an Augustinian Abbey of no small note; but it was not quite in the first class. Even the merchants’ great church of St. Mary Redcliffe was in the Middle Ages no more than a Chapel of Ease to the country church of Bedminster.

Tudor Bristol, like most of Tudor England, was the scene of change, restlessness and mental readjustment. But the spirit of benevolence was still alive; and this period gave to Bristol, both before and after the Reformation, much of the rich complement of endowed schools and charities that in the 1790’s aroused the admiration of Sir Frederick Eden. But Tudor Bristol was not always prosperous—for instance when the Spanish war had cut off her main outlet of overseas trade. Nor did it help her that under Elizabeth the Cabots should have sailed from Bristol on their famous pioneering voyages. It is a fallacy to suppose that the Newfoundland of 1497 was a colony of this country in the economic sense of the term. Had that been so, Bristol would have reaped the benefit; but real settlement in Newfoundland, and then mainly as a fishing station, was not completed till the days of James I. The merchants of Bristol prospered more from the exploitation of already settled colonies than from their first discovery or their initial planting. It was by this process, notably in Virginia, and by the revival of her Spanish trade which brought her “Bristol Milk” by 1634, that Bristol had achieved a degree of economic revival before the outbreak of the Civil War.

Provincial traders having been much harried by Court policy, it was natural that a majority of Bristol’s leading citizens should have been supporters of Parliament in 1642. Again, as five centuries before, their city was to play a key part in the struggle. I need say little of Bristol’s two sieges, though one likes to remember that Admiral Blake and a forbear of George Washington played notable parts—on different sides—in that of 1643 when Rupert took Bristol for the King. And it is at the end of the second siege, on 12th September, 1645, with the war already lost at Naseby, that we have the finest of all our portraits of Rupert. For he rode out after the surrender to Fairfax and Cromwell, “clad in scarlet, very richly laid with silver, mounted upon a very gallant black Barbary horse”. Thus appeared Rupert of the Rhine, not the victor-leader of a cavalry charge, but deep in defeat, riding out from the fortress that for nearly two years had been Charles’ most important stronghold in the country. Bristol was the largest city the Royalists ever held, their best arsenal, and for the landing of Irish and Welsh reinforcements their best port. Indeed there had been a proposal, soon after the first capture, that at Bristol and not at Oxford should be the scene of the Royalist Court. The Restoration brought economic revival and the real beginnings of the West India trade; also the growth and constant persecution of the local Nonconformists—particularly of the Quakers, in a city that, among her other Quaker memories, witnessed William Penn’s marriage. During Monmouth’s Rebellion, Bristol was both the rebels’ main objective and a firmly-held royal post. When Monmouth turned away from the city, the doom of his venture was sealed.

Now we come to Bristol’s greatest phase— the eighteenth century when the city was for a brief period the second in the Kingdom, the meeting-place of culture and commerce, and the scene of a magnificent building-boom that, in spite of Victorian rebuilding and wartime bombing, leaves her today still one of our chief Georgian cities. From the rich records of the age I would single out two salient years—1739 and 1798. In the first, John Wesley launched his open-air campaign before an audience of Bristol glassworkers and coalminers. During the second, a young Bristol bookseller brought out a little volume that he and its authors had decided that summer to call Lyrical Ballads. During the eighteenth century Bristol had Joseph Butler as her bishop and Edmund Burke as one of her Members. Josiah Tucker, not only Dean of Gloucester but also rector of Bristol’s leading mercantile parish, drew from his parishioners the material for his economic works. While his brother took the road, Charles Wesley lived and hymned for over twenty years in Bristol. This was the age of Bristol Delftware and porcelain, of Bristol glass and of the heyday of the Bristol metal trades. Major interests included shipbuilding, sugar and tobacco; and Joseph Fry and others before him undertook the manufacture of chocolate.

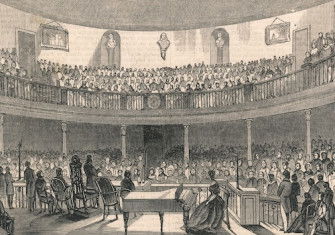

Bristol’s activities, moreover, had a wholly different aspect. In the Avon Gorge, near the spot whence the Suspension Bridge now leaps across the chasm, was the Georgian spa of the Hotwells, besides Bath the only hot spring in England. In its day it was a fashionable summer resort, which achieved literary fame in Humphrey Clinker and Evelina, but eventually gave way before the emergence of Clifton on the Hill. Here, to the west of the city, was a nucleus of Bristol’s cultural life; the “Quality” of the spa helped to fill the Bristol theatres, notably the exquisite and still surviving Theatre Royal, best of all our antique playhouses. Nor were the spa and the resort that followed it the only manifestation of Georgian Bristol’s cultural life. Before Southey was born there, before he and Coleridge and Wordsworth made of Bristol so vital a sojourning place, the city had seen the birth, in 1752, and most of the sad life, of Thomas Chatterton. She saw the births also of Hannah More and Sir Thomas Lawrence, and for a few weeks in 1788 the belated honeymoon of Capt. and Mrs. Horatio Nelson.

Bristol’s local industry, and her West India trade that went with it, must be considered separately. She could never have become England’s second city on the strength of her port alone, but attained that position because she was also a manufacturing town, a pioneer of the Industrial Revolution. Glass, pottery and sugar were only part of the story; there were metal industries too—and all depended on the local supply of coal. Bristol was the only dty of southern England that had a coalfield on its doorstep, small by modern standards but big enough to supply the comparatively small industries of those days. Most of the pits were to the north-east of tie dty, and it was among these rough miners of Kingswood and Hanham, a race of men apart, almost wholly outside the attentions of civic administration or organized religion, that John Wesley started his memorable campaign. Many of Bristol’s commercial magnates, particularly the great Quaker families, with their scruples about the slave system, made their living in industries fed by local coal.

But of all departments of Bristol’s life the most prominent was the West India trade. London, during most of the eighteenth century, was the leading West India port; but London had many other interests. To Bristol, with her great hinterland for the distribution of West India produce and a considerable re-export business, the West Indies were proportionately a far greater source of wealth. Nor was it only a question of importing semi-refined muscovado sugar and then finishing the process in Bristol; the city’s industries and those of the Midlands supplied the colonists with many of their daily needs. Bristol was inevitably a great port in the slave trade, and, for a few years, in the middle of the century, indeed the leading slave port. But slavers did not domiriate the connection with the West Indies. The ships that went out to the colonists, laden with such varied goods as Gloucester cheese and Taunton cider, clothes and books, furniture and tombstones, bottles in thousands—many of them full of Hotwell water—with carriages and building materials, did not go via West Africa and across the Middle Passage, but direct from home, via Cork for provisions and Madeira for wine to make sangaree, and then to Barbados down the North-East trades. The slave system—not necessarily the slave trade—was what made Georgian Bristol; and Emancipation, not the Abolition of 1807, came in the 1830’s as a far greater blow. By then there were other troubles in Bristol, notably the loss of all types of traffic caused by excessive harbour dues. The great riots of 1831, the worst and most spectacular of all the disturbances that marked Reform, had their roots deep in local economic distress.

Permanent decline, as never before or since, threatened Bristol during the first half of the nineteenth century. The North had become the main economic area of England. Bristol as yet had little to put in the place of her West India trade, now that the plantation way of life had permanently disappeared. The making of the floating, or tide-free, river-harbour, finished in 1809, had been a great achievement; it still means that the City Docks are a port for short-sea traders and coasters. But it failed to provide for the ocean-going steamers of the coming century; and the cost of the undertaking necessitated the high dues, which so effectively drove away sea-traffic that Wiltshire clothiers sent their goods abroad via Liverpool. Clifton helped, with its non-commercial incomes; but what in the end saved Bristol was the eventual construction below the Gorge of Avonmouth, and the increasing demand for such products as tobacco and chocolate, brought about by the higher standard of living among the working classes. By the end of the century the pattern of Bristol life was in many respects identical with her life today. During the twentieth we have seen the arrival of a great aircraft industry and a general increase in the engineering trades. Never a county-town, Bristol has now the status of a Regional Capital. Many a Government agency has its western headquarters in the villas of Clifton and in the ancient city itself.