The Protectors

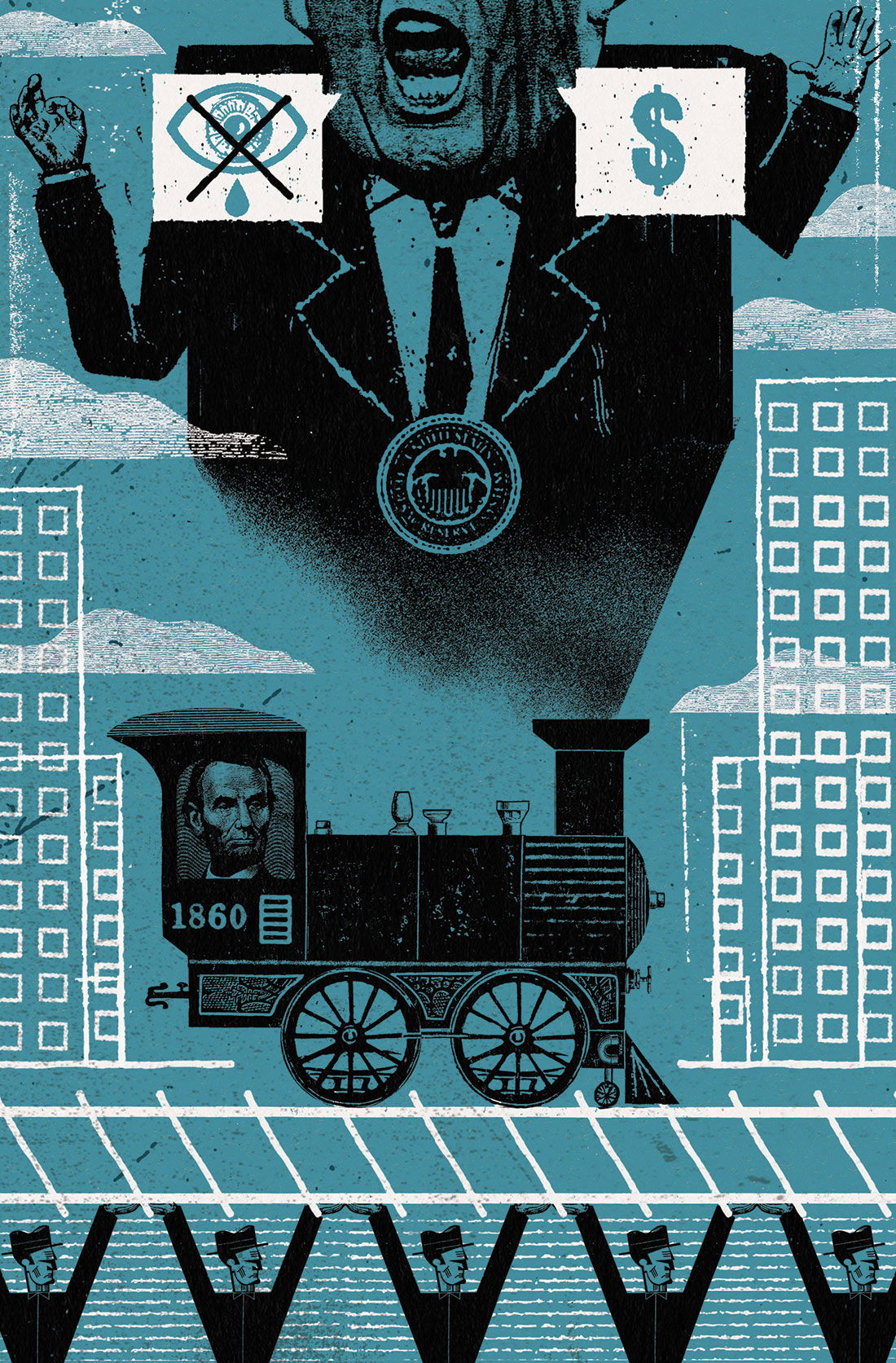

Many historical analogies have been drawn to explain the Trump phenomenon. Few have pointed out that the 45th president has something in common with his great predecessor, Abraham Lincoln. Both sought to shape an economy that benefited white working men.

Standing against a glossy backdrop on the stage of the Economic Club of New York in September 2016, Donald Trump, then a candidate for president, promised to ‘put new American metal into the spine of this country’. It was a strange pledge to make to Manhattan’s boardroom elite. Instead of invoking the slick sheen of corporate America, Trump conjured up the grit and dirt of heavy industrial labour, an economy that seemed distant both in space and time.

Standing against a glossy backdrop on the stage of the Economic Club of New York in September 2016, Donald Trump, then a candidate for president, promised to ‘put new American metal into the spine of this country’. It was a strange pledge to make to Manhattan’s boardroom elite. Instead of invoking the slick sheen of corporate America, Trump conjured up the grit and dirt of heavy industrial labour, an economy that seemed distant both in space and time.