The End of Imperial China

Yuan Shikai's short-lived reign as Chinese emperor ended on March 22nd, 1916.

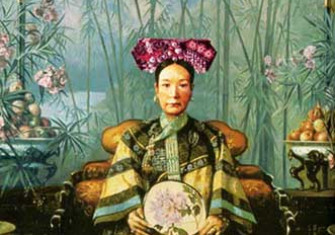

China had been ruled for centuries by successive dynasties of emperors, but by the later 19th century their day seemed to be almost done. The country was run on Confucian principles, which did not value change and progress, but stressed stability and peaceful harmony under rulers who enjoyed the mandate of heaven. As the western powers and Japan increasingly interfered in China, however, the divine mandate seemed to have been forfeited. Even the formidable Empress Dowager Tz’u-hsi felt forced to make concessions to the foreigners before her death in 1908 and a rebellion against her successor in 1911 turned China into a republic.

China had been ruled for centuries by successive dynasties of emperors, but by the later 19th century their day seemed to be almost done. The country was run on Confucian principles, which did not value change and progress, but stressed stability and peaceful harmony under rulers who enjoyed the mandate of heaven. As the western powers and Japan increasingly interfered in China, however, the divine mandate seemed to have been forfeited. Even the formidable Empress Dowager Tz’u-hsi felt forced to make concessions to the foreigners before her death in 1908 and a rebellion against her successor in 1911 turned China into a republic.

An assembly of delegates declared Sun Yat-sen, leader of the Kuomintang Party, provisional president of the republic, but he soon found himself in conflict with a powerful figure called Yuan Shikai. Yuan had started his career in the army and shown himself exceptionally competent, self-confident and ambitious. He had then risen to high positions under the Empress Dowager. He was now in command of the country’s principal military force and early in 1912 Sun Yat-sen, fearing civil war, made a deal with him. Yuan ordered the six-year-old emperor to abdicate, which he did, Sun resigned as president and Yuan replaced him the following day. Yuan was acceptable to the conservatives in China, and crucially to the army.Now at the age of 53 it was his job to stop the country falling apart.

The government had run out of money, the Chinese provinces were largely under the control of local warlords and the republic’s national assembly spent its time arguing and quarrelling. The Kuomintang, which had a majority in the assembly, kept opposing Yuan’s plans until he allegedly organised the murder of the party’s chairman. Effectively silencing the assembly, he operated

increasingly as a dictator with military support and in 1913 a rebellion broke out against him in the southern provinces, which he put down by force. Sun Yat-sen prudently withdrew to Japan while Yuan’s regime continued in power in Beijing and in 1915 he proclaimed a new Chinese empire with himself as emperor.

That was too much even for his conservative and military supporters and opinion turned against him. Armed rebellions broke out in the provinces and in March 1916 he abolished his new empire. He remained president of the republic, or so he maintained, until he died three months later in Beijing, at the age of 56. There would be more civil war until Sun Yat-sen formed an alliance with the Communist Party and made himself effectively the ruler of China until his death in 1925.