The Lost Obelisks of Egypt

The story of the transportation of three obelisks to London, Paris and New York captures the 19th-century mania for all things Egyptian.

The tale of how three 19th-century engineers – the Frenchman Apollinaire Lebas, the Englishman John Dixon (not forgetting his younger brother Waynman) and the American Henry Gorringe – managed to transport their respective obelisks to London, Paris and New York is hardly a new one. With the classic book on Egyptian obelisks, Labib Habachi’s The Obelisks of Egypt, having graced my shelves since 1977, I initially queried what more Bob Brier could possibly have to say. Through his choice of intriguing black and white images, however, he recaptures obelisk mania anew.

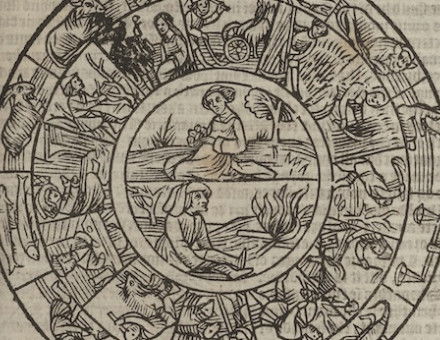

One image depicts a sea of spectators who gathered in 1836 to watch the newly arrived Paris obelisk being erected in the Place de la Concorde. In 1878 crowds on the Thames Embankment braved an hour of torrential rain, while hawkers sold souvenirs: photographs show penny pamphlet translations of the relevant hieroglyphs, together with lead obelisk-shaped pencils which graced the necks of fashionable ladies. Meanwhile, the band of the 17th Lancers played the popular Cleopatra’s Needle Waltz. A lively poster reveals that this was dedicated to Sir Erasmus Wilson, the surgeon-cum-philanthropist who had generously financed the project to the tune of £10,000.

Like his employee John Dixon, Wilson was a Freemason. So too was Gorringe. A stunning gold and amethyst baton, complete with a fully inscribed miniature gold obelisk, was used at the impressive Masonic installation ceremony for New York’s Central Park pedestal in 1881. Coinciding with the arrival of that city’s erroneously named Cleopatra’s Needle, storeowners dispensed carefully crafted trade cards. Needle and thread manufacturer John English & Co. showed Cleopatra threading one of its needles through a large hole in the obelisk’s upturned base, while J. & P. Coats depicted mammoth versions of their best six-cord spool cotton keeping the towed artefact afloat on the Hudson.

A 2014 photograph of a hard-hatted Brier clutching the top of the New York obelisk shows how, literally embracing a once in a lifetime opportunity, he climbed its temporary scaffolding. We, too, can therefore testify that its very tip had once been broken. Careful detective work results in the book’s final image – an enlargement of an 1870s photograph, sourced from France by a friend – of the obelisk still erect and minus its tip in Alexandria. Brier concludes that, before transport, Gorringe had its replacement cut and then reattached by means of a rod.

A fast-paced text, friendly chapter sub-headings, a few minimal footnotes and a useful bibliography assist the reader. It is, however, the unexpected illustrations that ultimately provide this book’s captivating originality.

Cleopatra’s Needles: The Lost Obelisks of Egypt

Bob Brier

Bloomsbury Academic

238pp £21.99

Rosalind Janssen is Lecturer in Education at the UCL Institute of Education and teaches Egyptology courses at Oxford University’s Department for Continuing Education.