Monuments to the Past

A nation built on symbols and a clear sense of history, the US increasingly recognises that it cannot defend the continuing presence of these statues in public spaces.

Hundreds of tourists from across the US file through Independence Hall, the ‘birthplace of America’, each day, past the Liberty Bell, through Betsy Ross’ House. History, tourism and public knowledge are all intertwined in this part of Philadelphia. This is a country well aware of the power of symbol and the resonance of monument and symbol – of ideas made tangible. The study of US National Parks and their curation of memory was instrumental in the development of what is now known as Public History, the study of how history is made available to wider audiences. The streets and sites of Philadelphia work physically to remind visitors of the astonishing feat of imaginative energy that the construction of the United States took and how that is maintained through constant vigilance and the cultivation of strong belief in the power of symbols and memories.

Nearby Gettysburg, the site of the biggest and most decisive battle of the Civil War (1863), pays tribute to everyone who died during the three-day battle, while carefully telling the story of the conflict, its origins and its consequences. The on-site museum celebrates Lincoln’s Gettysburg address, the Emancipation Proclamation and encourages a self-conscious and self-aware engagement with the past.

Wandering the field, however, things become more complicated. It is a site of huge re-enactment activity, for both sides. History ‘lives’ here and is interpreted through the bodies of the contemporary ‘performers’. The field of Gettysburg is a huge living commemoration of a horrific, bloody battle, but also a reminder of the continuing concerning resonance of the Civil War to contemporary American life.

There are around 1,300 commemorative statues and memorials to those who fell, erected by states and army regiments. On the field there are many erected to commemorate the Confederate states, dating 1886-2000 but predominantly pre-1965. This includes an equestrian statue of General Robert E. Lee (by Frederick William Sievers, 1917). Sievers also sculpted the statues of Stonewall Jackson and Matthew Fontaine Maury currently on ‘Monument Avenue’ in Richmond, Virginia (which also has a Lee statue by Antonin Mercié, 1890). ‘Monument Avenue’ has long been the site of protest and controversy around the commemoration of Confederate figures. Many of the Confederate statues in the Southern States were put up during the period 1900-1930 (during the period known as ‘Jim Crow’) or the 1950s (in response to the Civil Rights movement).

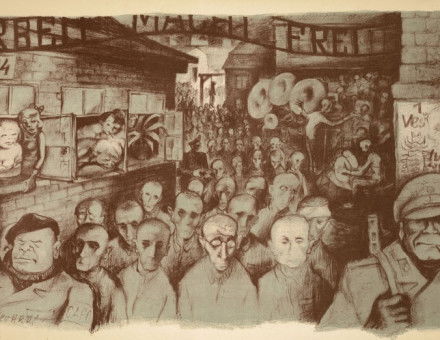

It was the proposed removal of another statue of General Lee – that in Charlottesville, Virginia – which prompted various Neo-Nazi, White Supremacist and ‘Alt-Right’ groups to demonstrate in a ‘Unite the Right’ march on 12 August, chanting antisemitic slogans and carrying racist banners. Violent confrontations with anti-Fascist protestors ensued. A car drove into the anti-Fascist protestors, killing Heather Heyer and injuring 19 others.

The events in Charlottesville prompted a huge response, with thousands of people seeking to demonstrate their solidarity with those who were protesting and their disgust with those who had chosen to march under Confederate and Nazi flags. Worryingly absent in this discussion was the president, Donald Trump, whose inadequate and slow response has been globally attacked.

Twitter and other social media are currently full of people attacking the events and pointing out the ‘ease’ with which one might choose sides, or rather echoing former Vice-President Joe Biden’s point that ‘there is only one side’. Tweets recollect relatives killed fighting in the Second World War, celebrate the struggle of the ‘Greatest Generation’ against Fascism, vindicate America’s leading place in the world due to its moral leadership in the 1940s and after. Opinion pieces proliferate about the similarities between now and the 1930s. Two key images have been regularly used: Captain America and Indiana Jones fighting Nazis. The invocation of Nazi Germany and Fascism makes an easy enemy, clearly understood, part of the cultural memory as evil and relatively uncomplicated. At times the invocation of the Second World War has worked to cloud the more pressing issues associated with remembering the American Civil War that the statues – and their removal – highlight.

The events have become situated at the resonant meeting point of Second World War memory and Civil War contestation. Discussions range from consideration of Civil Rights, citizenship, memory of the Holocaust, structural racism and inequality, the rise of Fascism, slavery and contestation of the legacy of the American Civil War. Often central to the discussion has been the place of memory in the identity of a nation, the ways that ethnically aware and astute citizens must be aware of the power of the symbols around them – or be complicit in what they seem to suggest and to allow in public life. What we have seen over the past few days is a phenomenal surge in debating public memory, identity politics and the relation of the past to the present.

Some ugly, difficult, unspoken issues are now being vigorously debated. The events have provoked people around the world to think about the symbols that sustain their nation, to look hard at the history behind that statue they walk past every day on the way to work, to think carefully about the implications of commemorative objects to the way that all citizens might feel about the country they live in. They are prompted to think about the ethics of remembrance. The institutions of memory in Philadelphia are not neutral and memory is always politically inflected.

The memory of the American Civil War is still incredibly strong and politically toxic. Overnight in Baltimore, Maryland the authorities took down four Confederate statues (having voted to do this a while ago) to prevent them providing further rallying points. Protestors toppled a Lee statue in Durham, North Carolina and demonstrators surrounded statues of Albert Pike in Washington, DC. Protestors point out that these statues are part of the lived fabric of the nation. In plain view they seem to show a country that celebrates slave-owners, violent insurgents and racists. They are the open declaration of racist politics, emblematic of a host of other continuing issues from police violence to structural inequality to the prison population to education to political representation. A nation built on symbols and a clear sense of history increasingly recognises that it cannot defend the continuing presence of these statues in public spaces. However, resisting the power of national symbols can be controversial or dangerous.

This is not simply an issue in the US. Countries from Chile to Hungary to Iraq have struggled with what to do with statues of former dictators or violent regimes. There are huge numbers of statues and commemorations around the UK, Australia and Europe relating to colonialism, war, slavery and empire. Some are controversial and debated – Colston Hall in Bristol, the statue of Cecil Rhodes at Oriel college in Oxford, John McDouall Stuart in Alice Springs, ‘Bomber’ Harris on the Strand, even the re-siting of a statue of Engels in Manchester – but many others are unseen or hitherto ignored. There have been some attempts to challenge them and to take them down, or to open up debate about how and what is remembered in public. These discussions are compelling and necessary.

History happens in public and the memory enacted in parks, squares and streets is important for the way a polity defines itself. How and what a nation chooses to remember, the strategies for commemoration and the implications for acts of memory; these are all deeply important and immediate issues for citizens of those states to engage with. What type of memory is appropriate, or not, and what kind of person is celebrated, set a tone and an example for the civic life of the country.

Jerome de Groot is Senior Lecturer at the University of Manchester.