The Northwest Passage: A Trump Card for US Arctic Policy?

Since the 1950s, the question of who owns the Northwest Passage has been a contentious one. With Donald Trump in the White House, the debate over sovereignty is likely to heat up.

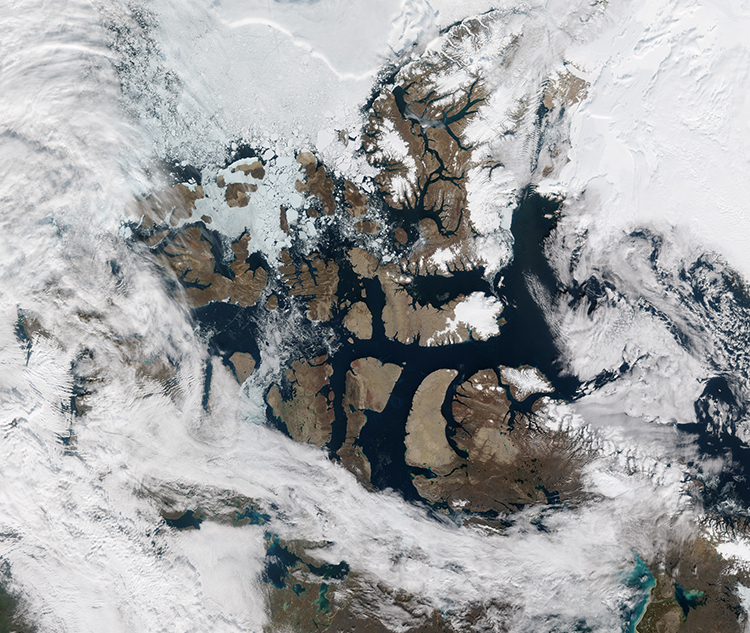

Every time a new measurement shows the the Arctic ice cap to be shrinking, there is a flurry of media interest and predictions that the fabled Northwest Passage will become a viable alternative shipping route for transit between Asia, North America and Europe. The ‘Northwest Passage’ refers to the sea route that connects the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans across the top of North America, via waterways through the islands lying between Canada’s northern continental coastline and the Arctic Ocean. As the ice cap retreats, this passage is becoming navigable for longer periods of the year. Ship traffic, however, still faces hazardous risks. The route is challenging not only due to the number of its bays, islands, uncharted shoals and narrows, but also because of drift ice and extreme weather conditions. In addition, other vessels sometimes do not record their positions or (in cases such as those of illegal fishing vessels) record false positions.

The Canadian government asserts that the Northwest Passage is part of Canada’s internal waters and subject to the nation’s full sovereignty. In fact, in 2009 the Canadian Parliament renamed the waterways the ‘Canadian Northwest Passage.’ In Canada’s view, no other nation has the right to navigate in or fly over those waters unless it consents. Canada enjoys sovereignty over the Northwest Passage based on historic title; a status conveyed by Canada’s (and particularly the Canadian Inuit’s) historic usage of those waters. This claim has long been challenged by the United States and other nations, which consider the passage to be an international strait through which they enjoy transit rights. This dispute arose in the late 1950s and has remained largely frozen since then, with both sides essentially agreeing to disagree. Since there have been so few transits over the past few decades, there has been little to shift the argument one way or another.

One of the weaknesses of the Canadian claim is that, under international law, Canada must show that its historic claim has enjoyed the tacit support of foreign states. Canada has certainly never enjoyed that support from the US; however, if any country begins using the Northwest Passage – and does so within the framework set by Canadian law and regulation – that activity will represent foreign acceptance of Canadian sovereignty. China may prove useful to Canada in this respect.

In an article published in the Wall Street Journal on March 10th, 2016, Canadian professor Michael Byers (along with US co-author Scott Borgerson) reprised an earlier suggestion aimed at bringing legitimacy to Canada’s claim of sovereignty over the waters of the Northwest Passage through a bilateral agreement between Canada and the US. The article, ‘The Arctic Front in the Battle to Contain Russia’, closes with the warning that the Canada and the US must reach agreement on the status of the waters ‘before it is too late’ because ‘there is little to stop an increasingly assertive Russia from sending a warship through’ the passage. To Professor Byer’s disappointment, the suggestion is unlikely to attract any support in Washington, D.C.

Recent statements from the White House make clear that the US is not going to acquiesce in Canada’s claims to sovereignty over the waters of the Northwest Passage. As reaffirmed in the Arctic Region Policy presidential directive, issued in 2009, the US position vis-à-vis the status of the Northwest Passage has been clear:

Freedom of the seas is a top national priority. The Northwest Passage is a strait used for international navigation … the regime of transit passage applies to passage through those straits. Preserving the rights and duties relating to navigation and overflight in the Arctic region supports our ability to exercise these rights throughout the world, including through strategic straits.

President Barack Obama hoped to leave a positive legacy in the Arctic and circumpolar north. He made an historic trip to Alaska in 2015. Initiatives to address Arctic climate change and environmental concerns, rolled out while the US chairs the eight-nation Arctic Council, have been high priorities for the outgoing president. Now President Donald Trump, a climate-change skeptic, is ready and able to rethink all of Obama's Arctic policies. The mainstay of Trump’s energy policy is working to establish energy independence by developing indigenous resources and creating jobs within the energy sector.

Trump has vowed to spend ‘at least double’ the $275 billion Hillary Clinton had proposed to spend on infrastructure over the next five years on projects such as roads, bridges, and ports. He is also especially keen to build more pipelines, including Keystone XL, and ‘approve private sector energy infrastructure projects’. While pipelines are a dead end in terms of leading towards an energy transition, at least their construction may temporarily employ people in places like Alaska.

Extended drilling in Alaska would be popular for many within the state, given that it would create many employment opportunities in one of America’s most impoverished states. Alaskan unemployment is the highest in the United States at 6.7 per cent and the region has a number of issues, such as high levels of alcoholism and high suicide rates, which are often linked to low employment opportunities. Creating jobs in the energy sector and pursuing US energy independence could be achieved through expanding Arctic drilling, granting more leases and removing environmental restrictions that prevent such efforts.

Preparing for increased drilling and shipping is something that the US will focus on in the years ahead. The country will have to increase the number of its tankers and explore new sea routes for oil delivery: the Northwest Passage could be the best way to solve this problem. Progress has been slow, but that is normal in the Arctic. Like it or not, Trump is certain to increase Arctic drilling and infrastructure in the years ahead. America will attempt to use the Northwest Passage to turn the situation to its advantage; time will tell if it is able to succeed.

Jeremy McCoy is a freelance writer.