A Historian Reads James Clavell’s Shogun

Though the real inspirations are obvious, James Clavell’s Shogun ‘exaggerates and often distorts the historical reality’ of feudal Japan.

When confronted with an extremely popular modern novel which is based on historical themes the first instinct of the historian, naturally enough, is to ascertain the ‘historicity’ of the work. The models for the major characters in James Clavell’s Shōgun are easy to recognise but Clavell has considerably rearranged and refashioned the events and personalities of the time about which he writes.

These changes can be summarised briefly. The model for Blackthorne, the protagonist of Shōgun, is Will Adams (1564-1620), the circumstances of whose arrival in Japan in April 1600 as pilot of a Dutch ship correspond closely to those of Blackthorne. Blackthorne's eventual rise to the position of adviser and retainer of Yoshi Toranaga roughly parallels the career of Adams; a key difference is that Clavell telescopes these events into a single summer, whereas in reality the intimacy of Adams and the historical Tokugawa Ieyasu grew over a matter of years. Clavell also inflates the heroic stature of the historical Adams by having Blackthorne actually save Toranaga's life, by having him introduce effective warfare with guns to Japan (something which had been accomplished several decades before), and above all by having him fall in love with the wife of one of the great feudal lords of Japan.

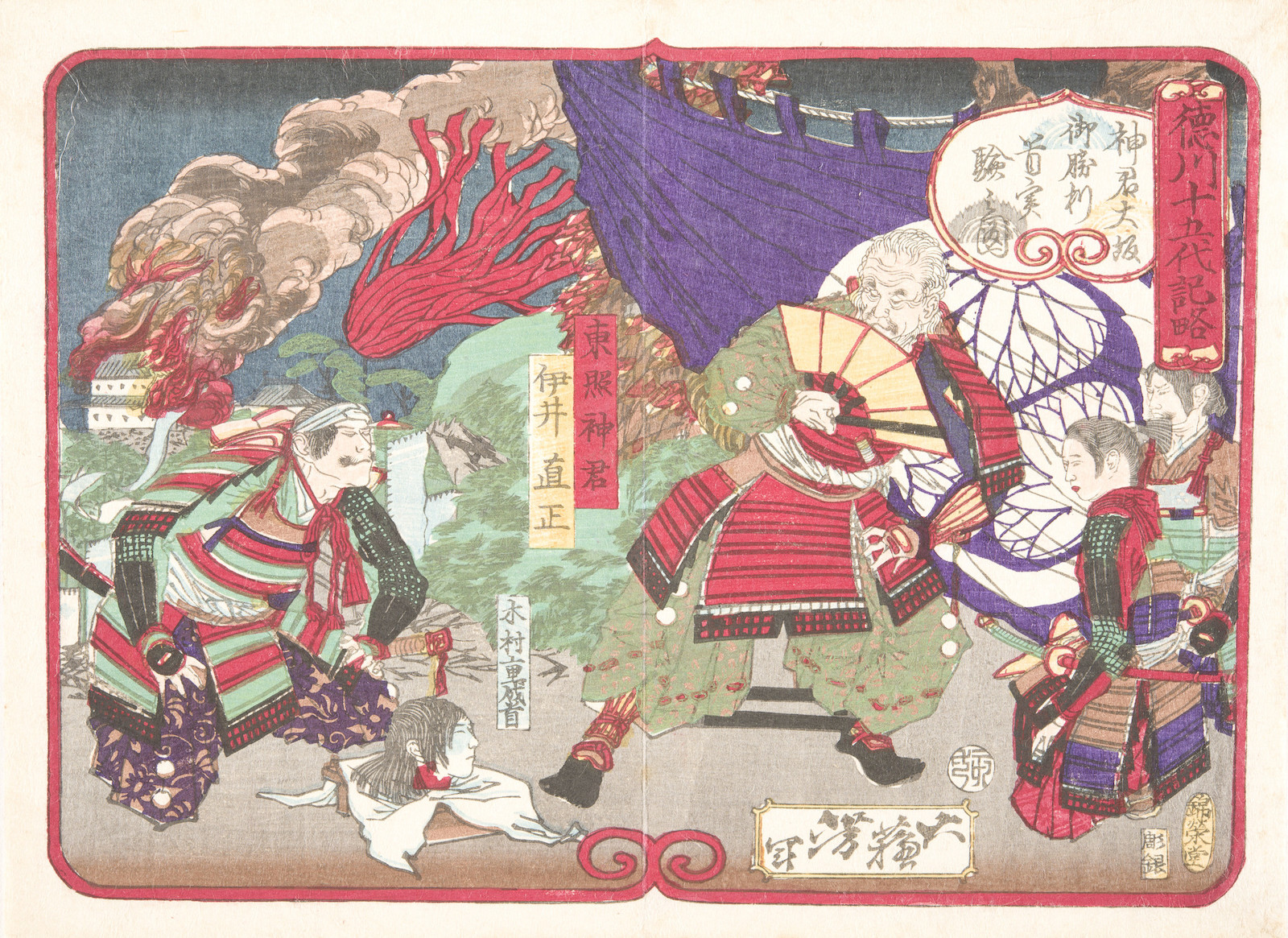

The depiction of the military struggle for national supremacy in Shōgun corresponds to historical fact in broad outline, although the intricate subplots of the novel are wholly of Clavell’s invention. Toranaga's scheming rival 'Ishido' is vaguely modelled after the daimyo Ishida Mitsunari (1560-1600), who did in fact organise the coalition against Ieyasu that was defeated at the Battle of Sekigahara in October 1600. The historical Ishida however, was not nearly so powerful as his counterpart in Shōgun, nor was his execution in 1600 anything like the gruesome punishment meted out to Ishido at the very end of the novel. Similar and even greater liberties have been taken with the other daimyo who appear in Shōgun, for many of whom it is even difficult to locate a specific model.

The model of Blackthorne's lover, Lady Toda Mariko, is Hosokawa Gracia (1563-1600), whose husband Tadaoki (1563-1645) was one of the most cultivated men of his time and is done somewhat of a historical disservice by being transformed by Clavell into the boorish ‘Buntaro’. The historical Gracia was one of the most famous of all the Christian converts in Japan of her era, and is revered to this day as a saint by Japanese Roman Catholics. While she was indeed versed in both Portuguese and Latin, the historical Gracia never served as an interpreter for Ieyasu. Nor did she even meet Will Adams, and she certainly would never have had a love affair with him or any other European seaman.

It is this transformation of a chaste Catholic heroine of the sixteenth century into a modish Madame Butterfly that has tended to shock and sometimes offend the sticklers for historicity. Edwin Reischauer, the distinguished American historian of Japan, has written indignantly that Clavell ‘freely distorts historical fact to fit his tale’ when he stoops to having such an ‘exemplary Christian wife’ as Hosokawa Gracia ‘pictured without a shred of plausibility as Blackthorne's great love, Mariko’.

These charges raise some difficult questions. As a novelist, is Clavell not free to transform his characters as he pleases? The author himself has claimed that there were really no exact 'models' for the characters in Shōgun, simply ‘sources of inspiration’ drawn from the pages of history. He did, after all, change the names of virtually all the historical characters (one notable exception being Gracia's maiden name, Akechi). ‘I thought, to be honest’, Clavell has said, ‘that I didn't want to be restricted by historical personality.’

The more serious charge against Clavell is that of historical plausibility: granted that the historical Will Adams never laid eyes on the historical Lady Gracia, was that sort of liaison conceivable in Japan of the year 1600? Here the answer would certainly be that it was not. The daimyo ladies of 16th-century Japan were strictly sequestered and rarely had the chance to meet any men other than immediate family. Nor can one imagine any Japanese woman of good breeding entering the bath so casually with another man – much less a 'barbarian'. The only sort of woman who would have behaved with the sexual candour of Mariko in that era would probably been a prostitute (such as Shōgun's ‘Kiku’).

The issue of historical plausibility arises on other occasions in Shōgun. A number of these relate to details about Japanese customs. The careful historian might insist, for example, that such a rare imported luxury as soap would not have been used to bathe a captured barbarian, or that traditional Japanese never celebrated birthdays (as Lady Ochiba does late in the novel), or that the Japanese did in fact eat meat from time to time (contrary to Mariko’s claim of total avoidance). In these and other small ways, Shōgun will strike the historian as a somewhat flawed depiction of Japanese customs in the year 1600.

Rather more of a problem is the question of Japanese psychology and behaviour as represented in Shōgun. Were samurai in fact given to beheading commoners on a whim and then hacking the corpse into small pieces? Were all Japanese of that era (or any other era, for that matter) so utterly nonchalant about sex and nudity? Would a peasant really have been summarily executed for taking down a rotting pheasant? Was ‘karma’ in fact such an everyday word among the Japanese of the year 1600? Although precise answers to these questions are not always easy, it can certainly be said that in every case Clavell exaggerates and often distorts the historical reality.

But the real problem is to understand why James Clavell has depicted the Japanese in ways that occasionally strike the historian as implausible. Most of the errors of detail were surely unintentional, and probably reflect nothing more than the inadequacy of the English-language materials on which Clavell, who reads and speaks no Japanese, was obliged to depend for his information. As a practical matter it must be admitted that such authenticity is probably of little concern to the average Western reader of Shōgun, who knows almost nothing about Japan or its history.

But the exaggeration of Japanese behaviour, particularly with respect to attitudes about such matters as love, death, food and bathing, is clearly intentional on the part of Clavell, since in every case he strives to contrast the values of the Japanese with those of Blackthorne and his fellow Europeans. Even more importantly, the final message of the author is that, as the confused Blackthorne comes to realise, 'much of what they believe is so much better than our way that it's tempting to become one of them totally'. Whereas Western man, as symbolised by Blackthorne, is depicted as ridden with shame over sex, obsessed with a fear of death, raised on an unwholesome diet of animal flesh and alcohol, and terrified of bathing, the Japanese are represented as paragons in each particular. They view sex and nudity as wholly ‘natural’, are able to face death with composure and even eagerness, eat only fish (preferably raw), rice, and pickles, and of course are wholly addicted to the pleasures of the hot bath.

It is precisely this rather didactic contrast that gives Shōgun so much of its interest, both for the average reader and for the historian. Clavell is in effect delivering a sermon on the errant ways of the West. More specifically, he is delivering a polemic against the Christian church for instilling in Western man his (in Clavell’s view) distorted attitudes to sex, death, and cleanliness. This anti-Christian tone runs throughout Shōgun and manifests itself most clearly in the depiction of the European Jesuits. Although no responsible historian would claim that the Jesuits were without their faults as missionaries in Japan, it is hard to find the priests of Shōgun as anything but caricatures. While the Jesuits did indeed for a time rely on the silk trade to finance their mission, they were scarcely the greedy villains of Shōgun, ever ready to stoop to crude assassination plots to thwart their rivals.

The preferable religious attitude, Shōgun insistently implies, is the meditative and fatalistic posture of the Japanese samurai, as epitomised by the great warrior Toranaga. About halfway through the novel there appears a description of Toranaga in a state of religious reverie; it is an effective summary of the type of mysticism which Clavell seems to advocate:

Now sleep. Karma is karma. Be thou of Zen. Remember, in tranquillity, that the Absolute, the Tao, is within thee, that no priest or cult or dogma or book or saying or teaching or teacher stands between Thou and It. Know that Good and Evil are irrelevant, I and Thou irrelevant, Inside and Outside irrelevant as are Life and Death. Enter into the Sphere where there is no fear of death nor hope of afterlife, where thou art free of the impediments of life or the needs of salvation....

While drawing freely on elements of Asian mysticism (karma, Zen, Tao), this sermon is a personal statement by James Clavell. A more authentically Japanese Zen Buddhist, for example, would certainly be far more respectful of ‘teachers’ and the idea of ‘salvation’. Yet the Zen spirit is certainly there, and the message is that the West has much to learn from Asian meditational practice – an idea to which many of Clavell’s devotees would seem to be hospitable.

In a sense, then, Shōgun is a story of a spiritual quest. It is of course skilfully woven in among other stories – that of a tragic love affair and that of a ruthless power struggle – so that the sermon never becomes obtrusive. But it is a very important element in the overall logic of Shōgun. Even less apparent to the normal reader is the fact that this ‘quest’ is closely related to James Clavell’s personal experiences with the Japanese. As a young soldier in the British army, Clavell was captured by the Japanese in Southeast Asia in 1942 and spent the remainder of the war in Changi prison in Singapore. While his experience understandably left him with many hostile feelings about the Japanese, he grew in time to respect his captors, for much the same reasons that Blackthorne does. In short, the story of Blackthorne’s progress, from horror over his captors’ ‘barbarity’ to respect for their ‘civilized’ values as even more ‘civilized’ than those of the West, is also the story of Clavell himself.

It is in order to dramatise this theme of spiritual quest in Shōgun that the author tends in various ways to idealise, over-simplify, and sometimes distort Japanese values and attitudes. And it is here that the historian can perhaps step in to right the balance a little.

One common form of exaggeration in Shōgun is the depiction of values which were historically limited to a certain segment of Japanese society as though they were universally ‘Japanese’. Take the simple example of eating meat. Mariko tells Blackthorne that the Japanese never eat meat. This was in fact true at the time only of the Buddhist clergy and the Kyoto aristocracy; the samurai class of which Mariko was a member was in fact fond of meat and frequently consumed wild game. One hastens to add that in terms of contrast with the Europeans, Clavell’s depiction is still basically valid. Even samurai ate only wild game, and never raised animals or even fowl for consumption; and never did their level of meat consumption even approach that of the highly carnivorous Europeans of all but the lowest classes.

Another type of simplification which the historian is anxious to pick out is anachronism. An appropriate example here might be that of sexual attitudes, a matter of fundamental East-West contrast as depicted in Shōgun. Here the problem lies primarily in the characterisation of European seamen as squeamish about sexual matters as Blackthorne is. The depiction of Western sexuality in Shōgun conforms instead to the stereotype known as ‘Victorian’ – although many people now question whether such prudishness was in fact typical of the 19th century.

In this process of trying to ‘de-idealize’ the sharp Europe-Japan contrasts that appear in Shōgun, however, the historian soon learns two important lessons. The first is that we still do not really know the answers to many of these questions about the historical evolution of Japanese attitudes to sex, love, death and other such basic human preoccupations. Nor, for example, do we really know what the Japanese of different classes ate in the 16th century. Nor indeed can we give a satisfactory explanation of the historical development and psychological workings of the peculiar samurai practice of ritual disembowelment (seppuku). The lament of French historian Lucien Febvre in 1941, would certainly still apply to Japan: ‘We have no history of Love. We have no history of Death. We have no history of Pity or Cruelty, we have no history of Joy.’ We cannot, quite simply, answer the hard historical questions about the stuff of which a popular novel like Shōgun is made.

The second realisation provoked by Shōgun is that no matter how much the historian seeks to qualify the rather stark contrasts between Japan and the West that run through Shōgun, there remains little doubt that in many ways Japan had by the year 1601) evolved customs and attitudes that really do seem to have been at sharp variance with those in the West. One has only to peruse some of the fascinating reports of European visitors to Japan to realise this. As the Italian Jesuit Alessandro Valignano (the model for Father Carlo dell’Aqua in Shōgun) wrote in 1583, ‘The things which they do are beyond imagining and it may truly be said that Japan is a world the reverse of Europe’. This metaphor of Japan as a ‘topsy-turvy’ land, where everything is done in precisely opposite manner, is one that has appeared again and again in Western descriptions of Japan ever since.

Western understanding of Japan has, we may hope, reached the point where we can dismiss the ‘topsy-turvy’ argument as Europocentric nonsense. This is not, however, to deny the reality of general differences between Japan and the West – provided of course that one remains alert to the wide diversity among different classes in Japan and among the many cultures that make up ‘the West’. It is precisely the general differences that make Japan such a fruitful and fascinating object of study for the West: by understanding Japan, we come to understand ourselves. It was the genius of James Clavell to mobilise this learning process as a central theme of Shōgun. It remains the task of the historian to probe the roots and refine the limits of Blackthorne's lessons.

Henry Smith Harry Smith is Professor Emeritus at the Department of East Asian Languages & Cultures, Columbia University. His books include Learning from Shōgun: Japanese History and Western Fantasy (1980).