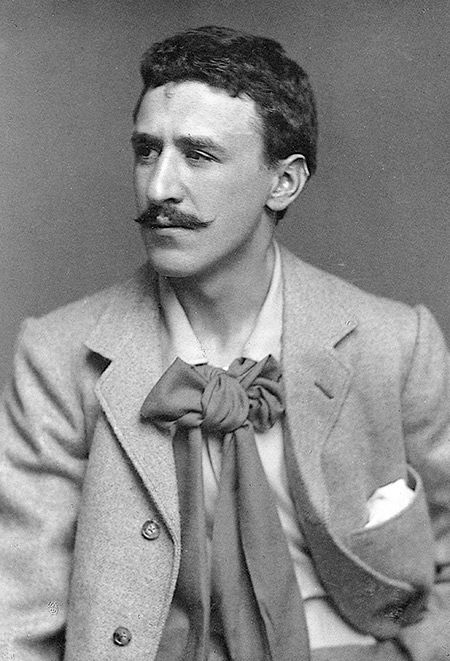

Charles Rennie Mackintosh: A Legacy and a Love Story

Behind the beautiful work of the ‘Father of Glasgow’ lay a deep and lasting love.

The fire at The Glasgow School of Art in May 2014 destroyed the magnificent library, devastating devotees of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, particularly Glaswegians, who look on him as the ‘Father of Glasgow’. It did, however, introduce his work to a wider community, many of whom thought it was limited to jewellery and designs destined to appear on carrier bags and tea towels. In fact he did not make jewellery, except one piece, which he designed for his wife, Margaret.

What is perhaps less well known is the enduring love match of Charles and his wife, Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh. They met as students at the old Glasgow School of Art in 1883. Little did they know that Charles would one day be the architect of the new Glasgow School of Art.

He was employed by the architectural practice of Honeyman and Keppie which, in 1897, won a competition with his design for the new Glasgow School of Art. Because he was not a partner in the firm, Honeyman and Keppie took the glory. But by then Mackintosh was already making a name for himself elsewhere.

The couple were married in 1900. Their home, which is now replicated at the Hunterian Gallery in Glasgow, was both beautiful and functional. Their collaboration in the design of the famous Willow Tea Rooms, commissioned by a Miss Cranston, was a work of art in itself. Meticulous attention to detail was apparent, right down to the teaspoons, china and the attire of the staff. During those heady days commissions kept them occupied and in addition to the tea rooms Mackintosh designed Hill House for publisher Walter Blackie. Margaret was well known for her fabric designs and paintings. By then Mackintosh had won prizes in Italy and Vienna, where he met Gustav Klimt and other artists.

This talented couple seemed to have the world at their feet but unfortunately their work was better known on the Continent than in Britain and by 1914 commissions had dried up and they moved from Glasgow to Walberswick in Suffolk. It was there that Mackintosh executed exquisite botanical watercolours. This was during the First World War and the local folk mistrusted the man with the strange accent who received mail from Vienna. Mackintosh enjoyed walking along the sea front at night carrying a lantern. The locals thought he was signalling to the German fleet and reported him. He was arrested and imprisoned while his wife was away and it was only on her return that she was able to convince the authorities of their mistake.

By 1923 they were seriously impoverished and decided to leave England to settle in France. Mackintosh’s watercolours during this time show both his love of nature and his architectural perspective. During all their trials and tribulations Margaret was by his side and there was no doubt of their enduring love for each other. One of his letters to her states: ‘You must remember that in all of my architectural efforts you have been the half if not three quarters of them.’

By 1923 they were seriously impoverished and decided to leave England to settle in France. Mackintosh’s watercolours during this time show both his love of nature and his architectural perspective. During all their trials and tribulations Margaret was by his side and there was no doubt of their enduring love for each other. One of his letters to her states: ‘You must remember that in all of my architectural efforts you have been the half if not three quarters of them.’

In 1927 Margaret had to return to London for six weeks for medical treatment, leaving Mackintosh alone and lonely in France. Mackintosh, who was mildly dyslexic, wrote almost daily to her, calling the letters his Chronycle, or Chronacle. The letters were never intended for publication but, after their privacy was breached and in order to preserve their authenticity, they were published in their entirety in 2001. Margaret’s replies were never discovered.

From these letters we have a moving insight into the enduring love between Margaret and Charles. He tells her he misses his ‘chum’ and his ‘lover’ and his concern about her health shows that he is worried as well as lonely without her.

This Chronycle seems to be full of fleeting impressions and disconnected sentences but anyone who can read their meaning would find only three words – I love you.

Money was still a problem and he writes on the thinnest paper he can find so that the postage will not be so great, injecting humour into the messages:

Writing lightly so that the weight of the lead in the pencil will not cause extra postage.

Tongue cancer forced him to return to London and he died in 1928, a disappointed and impoverished man whose early promise had not been fulfilled, partly due to the Great War and the lack of commissions during that period. Margaret died five years later and their estate was valued at £88.16s 2d. It is ironic that in 2002 the kimono-style writing desk that he designed was sold at Christie’s for £900,000 and in 2008 Margaret’s painting, The Red Rose and the White Rose, sold at auction for a sum in excess of £1,700,000.

In December 2009 a plaque was erected in Chelsea to celebrate the London years of Charles Rennie Mackintosh. His work can be seen at venues across Glasgow and beyond.

Barbara Butcher is the author of The Other Canal (Troubadour, 2011).